Coming soon: Hawramani Android and iOS apps

I am happy to announce that we have contracted the app developer Kurd Codex to develop Android and iOS apps for our website. This will enable our readers to follow our website’s updates on their smartphones.

Ibn al-Jawzi’s quote on combining opposites

What do jinns in dreams mean?

Is Allah a moon god?

Islam and downloading cracked software (piracy)

Who does “Woe to those who pray” refer to?

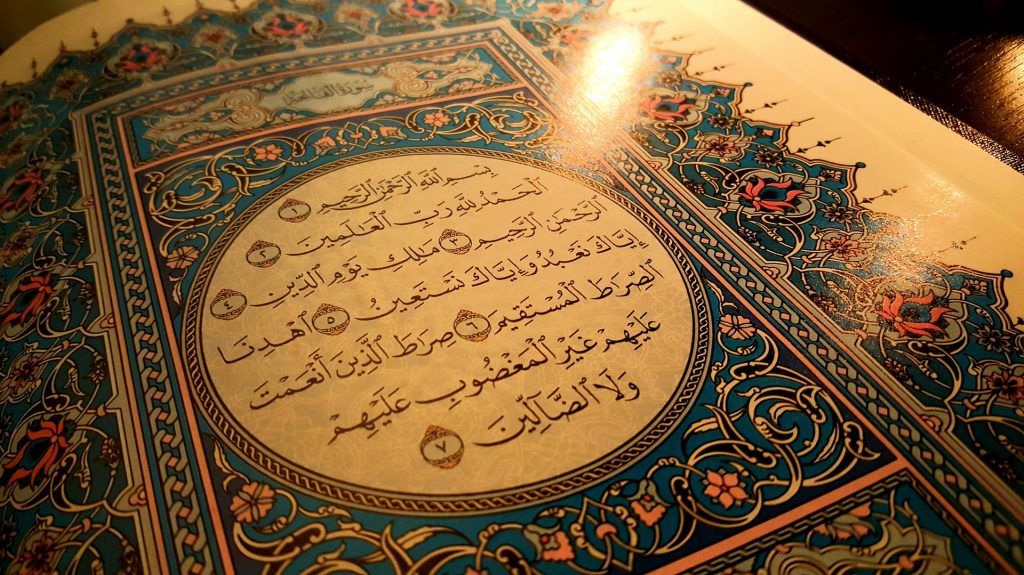

Why a Muslim should read or listen to the Quran for an hour every day

Assalamualaikum, from my readings I noticed that you consistently reminded us readers to at least allocate one hour a day to listen to the Quran. So, with regards to that how long have you practiced this and what changes have you felt ever since you started practising it.

Alaikumassalam wa rahmatullah,

I started seriously practicing this since last Ramadan when I promised God to spend an hour every day in extra worship.

Since I started doing that, everything in my life has seemed to go more smoothly and I have enjoyed numerous new blessings that I never expected.

The greatest benefit has been the fact that it makes sinning almost impossible. It feels like God is always with me and I cannot engage in any sinful idea without feeling His strong presence. So it is a way of ensuring true submission to Him.

Another benefit is that it feels like my life is on a course managed by God. I do not care what happens tomorrow, next month or next year. God is in charge and He will ensure my good. So it has completely removed all anxiety I have had about the future.

To me therefore it seems like a Muslim who wishes to be extraordinary and who wishes to achieve the peak of spirituality should make this a daily practice that they plan to do for all of their lifetime. There is nothing better than always being in God’s presence; it takes life’s problems away, it takes away all sins, it makes life meaningful and it brings constant new blessings. Problems that seemed unsolvable to me in the past have disappeared.

A village imam was found in a brothel

Solving the Problem of the Codification of the Sharia

Abstract

I argue that the existence of an inherent contradiction between the Islamic Sharia and codification is imaginary and caused by paying insufficient attention to the nature of the workings of the Sharia and how it relates to the state. So far codification has meant the imposition of the hegemony of the state over the Islamic legal process. It is possible to create a legitimate and authoritative Sharia code by reversing this process: imbibing the ideals of the Sharia into the legislature and making its principles the governing doctrines on how the process of codification should be carried out.

In law, codification is the process of collecting legal rulings into a legal code or book of law that is then made the official source of law for a jurisdiction, for example for a town or country. Traditional Islamic law until the 19th century was alien to codification because codification was a bureaucratic need that was only recognized in that century after the influence of Western legal systems. The first important attempt at the codification of Islamic law was made in British-controlled India.1 The British considered the Islamic practice of law as “as an uncontrollable and corrupted mass of individual juristic opinion” according to Wael Hallaq.2 Hallaq considers the British attempt at codification as an outgrowth of colonialism. Islamic law was severed from its roots in order to fit in with British ideals of how the law should function.

The Ottoman Mecelle of 1876 was the first attempt by a sovereign Islamic state to codify Islamic law.3 Samy Ayoub considers the Mecella a legitimate outgrowth of the Hanafi legal system of the Ottoman Empire,4 while Wael Hallaq considers it a state imposition that by steps almost totally replaced the Sharia.5

The essence of Islamic jurisprudence was the constant re-analysis of the sources of Islamic law in order derive new rulings (fatwās) based on the individual and autonomous research of a jurist (muftī). According to George Makdisi, a jurist could not even rely on his previous rulings to create new rulings; this would have been considered an unacceptable breach of the jurist’s duty to constantly re-analyze the sources of Islamic law (the Quran, the sunna, the consensus of past scholars, and Medinan ʿamal in the case of the Mālikī school).6

Islam gave rise to the concepts of academic freedom and the doctoral dissertation, only adopted by the West after centuries of conflict between the Church and the universities. Since Islam has no official ecclesiastical hierarchy, each professor of the law (jurist or muftī) had to be an independent authority who could profess independent, autonomous opinions on matters of law. The very term “professor” comes from Islam: a professor is someone who has studied the law sufficiently with a master and who has produced a taʿlīqa (doctoral dissertation), an original thesis that proves his competence as an independent thinker.

Islam’s muftīs were the world’s first professors. Islam, however, never extended the concept of the professor beyond the field of Islamic law. It was Western civilization that took this step and created the concept of “professor” as an independent authority on any field of knowledge.

Since Islam lacks an ecclesiastical hierarchy that can decide issues of orthodoxy, the only way to ensure arrival at consensus in a legitimate way was to adopt academic freedom. A legitimate fatwā in Islam is one that is given by a professor who enjoys perfect academic freedom to agree or disagree with anyone else. The West had no need for academic freedom because the true authorities on matters of religious doctrine were the bishops in unity with the pope. Islam, lacking such authorities, was forced to adopt a rational way of arriving at authoritative religious rulings in their absence. And the solution was the academic freedom of the professor or muftī. When all the professors, in perfect freedom and autonomy, agreed on a particular ruling, that meant that the ruling was authoritative.

Orthodoxy in Christianity was determined by the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Orthodoxy in Islam was determined by the autonomous consensus of the professors, just as in modern science. In science a particular theory can only become “orthodox” when all eligible scientists study it and arrive at a consensus about its reasonableness and likelihood of correctness. Islam was forced to create this “scientific method” of arriving at consensus due to suffering the same situation that science suffers: there is no higher authority than the scholars, researchers and professors themselves to help them come to legitimate conclusions on the issues under question.

From the 19th century onward, many Muslim states adopted Western legal codes as part of their process of modernization. While many of these codes purport to respect the Sharia or to consider it a primary source of law, the reality is that they are forced to break the very foundation of the Sharia in their efforts to codify it.

The Sharia functions, like science, on the basis of the autonomous consensus of the professors. Governments, however, want stable legal codes that they can control. The call for the Islamization of the law in various Muslim countries has always ran into the contradiction between the Sharia’s system of autonomous consensus and the Western legal practice of creating legal codes.7 A Pakistani court adopted the punishment of a hundred lashes for married individuals found guilty of zinā (fornication). Traditional religious scholars found this an unacceptable breach of Islamic law since the traditional punishment for such individuals is stoning to death.8 The government of President Zia ul Haq, in order to maintain the support of the scholars, called for a rehearing of the case and changed the composition of the court to include traditionalist scholars. The result was that the court arrived at the traditional ruling of stoning to death.9

From the Sharia perspective, the artificial creation of a new ruling such as this that becomes the authoritative law of the land is a miscarriage of jurisprudence, since it destroys the Sharia’s reliance on the autonomous consensus of the professors of the law and replaces it with a government-elected clerical regime. The new legal code abolishes the academic freedom of the professors of the law and replaces it with the government’s monopoly power over the courts.

Professor Ann Elizabeth Mayer, in relation to the conflict between the Sharia and codification, proposes the establishment of a new doctrine toward it that somehow makes it accommodate codification, while admitting that it will be a delicate and painful process. But rather than seeking to abolish the Sharia’s autonomous foundations in favor of rigid codification, a synthesis is possible that embraces both modern democratic ideals of legislation and the Sharia’s autonomous nature.

The synthesis of the Sharia and legal codification

By understanding the workings of the Sharia, translating its ideals to the realm of modern legislation becomes a somewhat simple exercise. The “Islamization” problem of the modern Islamic state is not with Islam or secularism, but with the way the state attempts to enforce its hegemony over the communities it governs, as Noah Salomon argues.10 Anver M. Emon argues that critiques of the codification of Islamic law are often based on an ideology of the way the state functions or should function, rather than on an inherent contradiction between Islamic law and codification.11 I believe that it is possible to envision a state legislature that can fully represent the ideals of the Sharia while working within a codified system of law.

Authoritative Sharia rulings demand that the lawmaking authority should be made up of professors of the law that enjoy the following characteristics:

- The attainment of formal education under the masters of the law and the presentation of an original doctoral thesis that proves their competence to profess independent rulings.

- The academic freedom to profess opinions arrived at through personal, independent research that is not in any way influenced or controlled by a higher authority.

What an Islamic state can do is to bring together all willing professors of the law into a legislative council, for a example a house of parliament, where they can debate aspects of the law and pass rulings. Such a council, rather than being made up of elected professors, should automatically admit all professors who have proven their competence in their field (for example by getting their doctoral degree). This allows for the creation of a lawmaking body that is made up of all eligible professors in the land, just as in the traditional practice of Sharia lawmaking where every professor had the right to participate in lawmaking. Government interference with the admission process of professors into the legislative body will naturally corrupt its essential essence of autonomy, since the government will be able to support the laws it desires by choosing to admit only the professors that support the state.

In many Arab countries top religious officials are selected by the state. George Washington University Professor Nathan J. Brown describes this type of control over religious institutions as both imposing and clumsy.12 The control of the Egyptian military regime over al-Azhar University has lead to renowned scholars like Yusuf al-Qaradawi describing government-elected jurists like Dr. Ali Gomaa as “the jurist of the soldiers.”13 It is clear that state interference with Islamic lawmaking is self-defeating: A state-controlled process cannot achieve the all-important aspect of legitimacy that traditional Islamic law enjoys. In this way state laws enjoy neither legitimacy nor the widespread support of the Muslim populace.

Speaking of our imagined “council of the professors of the law”: When disagreements arise, the lawmaking body can decide matters based on the votes cast by the professors. The ruling that gets the most votes is the one that is integrated into the legal code. Dissenting opinions will also be integrated into the code, so that citizens can be given the choice to act by the dissenting opinion where this is feasible, similar to the way that the four-school courts of the Mamlūks functioned.14

It would be logistically unfeasible to convene all of the law professors, who may number in the many thousands, into a single legislative house. Instead, the legislative body can work by issuing calls for fatwās from all of the professors without requiring them to convene. The legislative body can then collate all of the fatwās and determine which ruling has the most support.

And in order to protect the integrity of the process, a legislative council can be elected by the professors themselves that oversees the process of issuing fatwā calls, collating fatwās and integrating them into the legal code.

Each professor should have the right to propose a change to the legal code. Whenever a change to the legal code is proposed, a new fatwā call can be issued and the professors can either stand by their previous fatwās or issue new ones.

In this way a stable legal code can be created that enjoys the widespread support of the professors of the law and that satisfies the principles of the Sharia: academic freedom, non-exclusivity and changeability (the ability to always go back to the sources and reach new rulings). In this way a living and constantly up-to-date legal code can be created. Since some aspects of the law are highly specialized, each specialization can have its own council and professors.

They cannot stop sinning despite their worship and feel like a hypocrite

Loving someone but sexually desiring another person

Is studying hard science a form of worship (ibada)?

Western vs. Asian mental abilities

Mentally disowning one’s family

Her father does not support the family because they receive welfare

Are disturbing dreams a sign of a bad character?

Medieval Female Mystics of Islam

A review of Arezou Azad, “Female Mystics in Mediaeval Islam: The Quiet Legacy.” (Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 56 (2013) 53-88).

Andrea Cabrera

The article, “Female Mystics in Medieval Islam: the Quiet Legacy” was written by Arezou Azad, who is a Leverhulme Research Officer of the Oriental Studies Faculty at the University of Oxford.

In this paper, we find a brief and summarized information about a 9th century female mystic Umm ʿAlī, from Balkh.

Azad starts by mentioning the lack of reliable sources that may enable researchers to find more female mystics from the past, which can be due to some external reasons that do not outline lack of interest from women’s side, lack or preparation or possible social repression. In fact, as the article mentions, a great number of female scholars were found during the first century after the advent of Islam, then we find another peak of female presence during the 9th century, declining again until the 12th and 13th centuries, where we find once again traces of female scholars.

Umm ʿAlī, despite being a Sufi, can be considered a good example of determination and commitment toward education. Born in a wealthy family from the upper class, Umm ʿAlī is the granddaughter of a governor from the Abbasid regime in Balkh, which helped her inherit a great amount of money, enough to pay for her journey to Mecca to perform Hajj and her studies in that city for a period of 7 years.

In the paper we find two versions of Umm ʿAlī: the first one is an educated “worldly” woman who even lectures her husband, the renown Sufi scholar Abū Ḥāmid Aḥmad Khidrawayh, on how to hold dinner for another famous Sufi scholar. She was manly enough to ask her husband to marry her to her teacher, in front of whom she even removed the veil from her face, provoking her husband’s jealousy.

The second version shows us a more refined and centered woman, who supported all of her husband’s views. The masculine attributes are not mentioned, nor the nominal marriage to her mentor.

Due to lack of references it is hard to conclude which version is the accurate one, for example whether she just pursuing increasing her knowledge at any cost. The article leaves the door opened for the reader to create her/her own opinion of Umm ʿAlī, but highlights her educational achievements and the great importance that female education was given in Islam, which unfortunately, has been fading away because of some un-Islamic views.

Ikram Hawramani

In her paper, University of Birmingham professor Arezou Azad studies the career of the medieval female mystic Umm ʿAlī Fāṭima of Balkh.

Azad complains that it is often difficult to distinguish fact from myth in the accounts on Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya (d. 801). This is the case with lives of the Sufi saints since their disciples and admirers, removed from them by generations and centuries, naturally felt a strong urge to elevate their masters to the highest spiritual stations. Therefore Sufism never developed strict criteria for telling fact from fiction when it came to information on the lives and sayings of the saints.

Azad also complains that most recent research has focused on Rābiʿa. Her paper is a contribution toward shifting the focus to other female mystics of Islam. She mentions that over the past two decades (meaning 1993-2013), studies have revealed that women exercised far more power than was previously believed. This is a welcome observation and in keeping with my contention that the historical reality of male-female relationships is that women were always equal partakers in all civilizations, despite what feminist theories of historical misogyny might suggest (of course, the existence of some misogyny has always been a fact). And based on this contention, I hope to work toward contributing a post-feminist, or what I simply call a humanist, perspective toward the study of women that assumes from the get-go that men and women are already equal in power, worth and civilization-forming ability. A study by University of Western Ontario professor Maya Shatzmiller found that “women were involved in economic life in medieval Islam to an important degree.”

Columbia University professor Richard W. Bulliet has stated that the inclusion of women in the classical biographical entries were often due to their kinship ties with the compiler. This is in keeping with Darwinian theories of kinship where humans are wont to see people of closer kinship as “more human” than people of more distant kinship. It is to have a female-excluding worldview in a masculine scholarly culture, but kinship ties make it difficult for the male writer to uphold this exclusionary view toward closely related females. While a man may have a general view toward women, this view is difficult to uphold toward women he knows personally. An aunt, for example, is automatically excluded from the female category in the mind and included in the human category instead, this making it much more likely for the male writer to treat her on human terms rather than mere female terms.

Azad mentions that the 14th century Egyptian scholar Ibn al-Ḥājj (d. 1336 CE) spoke against women sitting across men during learning sessions, considering inappropriate. But she makes the astute remark that rather than his perspective, rather than representing a widely-followed norm and prescription, actually represents the opposite. Women’s free mingling with men in mosques had become a reality and this scholar simply tried to express his disapproval of it. In my book An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Understanding Islam and Muslims, I caution against viewing Islamic scholars’ statements as representations of norms since they often actually represent the opposite; they are anti-norms that they only wished to become norms. When Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 1201) complains about various errant practices in the Baghdad of his time, while a casual reading by a past Orientalist may have led him to think of the Baghdadian culture of the time as a theocratic society controlled by scholars, the evidence actually suggests the exact opposite: scholars had little power to control their societies, showing the great freedom enjoyed by the Muslims of the time. The reality of Islamic societies is that the elite of Islam (the scholars and the devout Muslims) often as a class stand against the elite of society and the “ordinary” Muslims. The Islamic elite always pull in one direction (toward a better practice of Islam), while the rest of society often pulls in the other direction (toward slackness and freedom). In this way a dynamic equilibrium is reached that cannot in any way be honestly described as a theocracy.

However, it is true that in classical Islam there was often a partnership between the social elite and the religious elite, as Azad discusses. But I believe this does not disprove my thesis since we have numerous examples of the religious laxity of many of the social elite of classical Islam. It was, for example, an extraordinarily pious step when one of the Abbasid caliphs decided to ban alcohol drinking-houses, showing that the Caliphate’s usual policy had been one of tolerance toward such an un-Islamic aspect of their society.

In her paper, Azad focuses on the career of Umm ʿAlī Fāṭima of Balkh, a female mystic and a member of the elite of Balkh’s society mentioned in a number of Sufi-oriented Iranian sources. She was taught tafsīr by Ṣāliḥ b. ʿAbdallāh al-al-Tirmidhī (d. 853-4) and transmitted his book in this field. She stayed seven years in Mecca after performing the pilgrimage in order to seek knowledge. This was not unusual. Davidson College professor Jonathan Berkey mentions that out of 1075 women listed in a biographical dictionary of the fifteenth century, 411 obtained a similar education.

Umm ʿAlī’s husband was the judge and mystic Abū Ḥāmid Aḥmad b. Khiḍrawayh (probably died 854-5). Umm ʿAlī took the interesting step of proposing to her husband. Al-Ḥujwirī (d. 1077) mentions (to use Azad’s translation, the first note in brackets is mine):

When she changed her mind [about not marrying], she sent someone [with a message] to Aḥ mad: “Ask my father for my hand.” He did not respond. She sent someone [again with a message]: “Oh Aḥmad, I did not think you a man who would not follow the path of truth. Be a guide of the road; do not put obstacles on it.” Aḥmad sent someone [with a message] to ask her father for her hand.

Azad narrates an anecdote in which Umm ʿAlī “removes the veil from her face” upon meeting the famous mystic Abū Yazīd (Bāyazīd) al-Biṣtāmī (d. 874 or 877-8) Al-Ḥujwirī recounts this as “Fāṭima niqāb az rūy bar-dāsht” (Fāṭima removed the niqāb from her face) (while her husband was present). This suggests that she merely broke a social convention rather than Islamic law—she did not necessarily remove her full ḥijāb. She simply trusted the great mystic enough to break social convention and let him see her face, believing that he would not objectify her for her beauty and attractions but continue to see her as a fellow human mystic. Elsewhere it is mentioned that once when Bāyazīd comments on the henna designs she has on her hand, she decided to stop learning with him, believing that this was an unacceptable breach of etiquette—the great mystic had taken note of her external appearance. Thus rather than suggesting any laxity toward religious law, the anecdote suggests her high character and her bravery in breaking social convention due to the trust she had in the power of the mystical path upon men.

In conclusion, Azad’s study is a very welcome contribution to rejuvenating the legacy of Islam’s great women in the classical period.