Do you need to face the qibla when making dua?

Believing Women in Islam (2019) by Asma Barlas and David Raeburn Finn

Get it on Amazon

Believing Women in Islam: A Brief Introduction by Asma Barlas and David Raeburn Finn is a short book that attempts to present the main ideas of Barlas’s longer work “Believing Women” in Islam: Unreading Patriarchal Interpretations of the Quran.

First, I should mention that I believe that any self-respecting and civilized man should demand that his female mate be his equal–he cannot enter into a relationship with an inferior being because that is damaging to his own self-respect. If I love a woman, I should love her as an infinitely respected person, not as a “woman” who is somehow categorically inferior to men.

I dislike the label “feminist” because I believe focusing exclusively on the rights and issues of any particular group of humans (women, children, men, Sunni Muslims, Jews) always invariably leads to injustice because it promotes a lack of empathy toward those who are excluded. It is far more civilized, humane and constructive to focus on the rights and issues of infinitely respected, dignified and inviolable persons regardless of what grouping they belong to. Just because a boy or man happens to have male sex organs is in no way, shape or form a good reason to consider his emotions and sufferings of any less importance than a woman’s.

In fact, I believe there is something deeply misogynistic about the feminist worldview (not necessarily shared by all feminists) that women are somehow the perpetual victims of history who were little more than animals controlled by men, lacking any sort of courage, agency or self-assertion. I rather subscribe to the worldview that women were full partakers in history–they chose, they self-asserted, they contributed, they were as much full-human members of their societies as the men were. The theory of the patriarchy is the misogynistic theory that men are somehow, miraculously, capable of keeping women at an inferior position compared to themselves, in something of a master-slave relation, perpetually. Are women so mentally and spiritually inferior to men that they should have put up with such a dynamic for all of history until a few feminists came along to enlighten them? I believe this is incredibly demeaning toward women’s courage and capabilities. Yes, throughout history there were various restrictions on women–but the crucial factor is that the women themselves helped maintain these restrictions. They were not like herd animals controlled by men as patriarchy theory claims–they were full partakers in their civilizations who accepted and supported the particular treatment of women in their societies.

Men and women are both equally responsible for the treatment of women in their societies. It is an insult to women and a figment of the imagination to think that the treatment of women in society is entirely or even largely men’s business. I am not saying that things were great for women, but that women themselves, as free human agents, fully contributed to the way women were treated in their societies. Women were not helpless witnesses to the abuse of women as is often portrayed by feminist ideologues. They took part in it, for example by inciting male relatives to keep their wives “in check”, by enjoying the knowledge that a woman they disliked was being abused, and mothers-in-law were throughout the world often quite happy to be utterly abusive toward their female brides. Any theory of women’s status and abuse that ignores women’s support for the abuse of women is ignoring reality for ideological motives.

If the treatment of women was unjust in a society, then a brief survey of the same society would show us that the men too suffered various forms of mistreatment despite their greater freedom of movement. The problem of their societies was not some anti-female conspiracy, it was a lack of appreciation for the rights and dignity of persons. And if the rights and dignity of persons is appreciated and promoted throughout society, women naturally become men’s equals without any need for feminism promoting women’s rights in particular. If you see the infinitely respected person inside a woman, then her woman-ness becomes completely irrelevant to how you love her and treat her. Her personhood is so incredibly important that her sex organs have no way to overshadow it.

Get it on Amazon

Why can’t we have a larger movement inclusive of both men and women that promotes the rights and equality of all persons regardless of their gender or race? This is in fact what classical humanism promotes. Not the arrogant secular humanism that considers humans somehow perfect and needless of guidance, but the humble, self-aware humanism of philosophers like Tzvetan Todorov inspired by the great French humanists. If we take to heart humanist teachings about the dignity and inviolability of persons, this automatically embraces all that moderate feminism truly stands for while avoiding the harms that come from focusing exclusively on the interests of a particular group of humans.

The founding myth of today’s feminism can thus be summarized as “Women were always subhuman until we feminists came to correct matters.” Believing Women in Islam fully assumes the truth of this myth and relies on it for its analysis, and for this reason it has little to offer beyond rehashing already-existing feminist views.

Barlas and Finn write, regarding the apparent lack of sufficient emphasis on women’s rights in the Quran and Sunnah:

God either (1) could not locate or (2) did not care about misogynistic practices in jahili societies. And don't think these stark alternatives are the end of the problem for patriarchal apologists. If God is all-knowing, God either knew and cared or failed to note or care about future generations.

There is a third possibility that they disregard due to the limits of their feminist framework. The third possibility is that women, as full partakers in human civilization, are able to fend for themselves. They support the treatment of women in their own societies even if it has unjust elements the way men support the treatment of men in their societies even if there are unjust elements to this treatment. Their worldview envisions half of society as somehow asleep, or as inferior humans, animals, who were somehow totally incapable of controlling and directing the course of their civilizations. This is utter nonsense–a figment of the feminist imagination. Women are full humans and they are as much responsible for the nature and elements of their civilization as the men are. The Quran and Sunnah lack feminist verses because they consider men and women already equal before God, already equal partakers in civilization, and therefore in no need of classifying one gender against the other and constantly telling one gender to be nice to the other because in this there would be an inherent misogyny. Telling men to be feminist toward women tells them that women are inferior creatures, children, who must be treated not as equals, but as inferiors deserving favors. It is much better and more intelligent for the Quran to simply treat all Muslims as persons, knowing that the men and women are together full partakers in civilization and require no special motivation for one side to avoid mistreating the other–because they are already equal, already they have equal power to shape, form and control their civilization and fend for themselves. The “patriarchy” is the myth that men are clever enough, powerful enough, and women inferior enough, stupid enough, for men to have a position of privilege over women that women are totally incapable of doing anything about. This is a rather low opinion to have of any human, male or female.

Regarding the hijab-related verses of the Quran, they write:

But the so-called modesty verses are specifically addressed to the Prophet and are advisory, not compelling. They are counsel, not commands. Cloaks and shawls in that era covered bosoms and necks, not heads, faces, hands, or feet. Moreover, the counsel was designed specifically to differentiate believing women in Mecca from slaves and prostitutes at a time when jahili men commonly abused both. The jilbab marked believing women as off-limits.

What they recommend is what I call “historical localization” of the Quran. The Quranic verses on the hijab were meant for a specific time and place and not for another. I refute this view of the hijab verses in this article.

So here is the question: Are Barlas and Finn willing to give women the right to interpret these verses for themselves? And if 99% of devout women interpret these verses as requiring the hijab in the modern world, are Barlas and Finn willing to admit that as full humans, these women have the right to interpret these verses in this way even if it goes against the interpretation of the two of them?

I believe in a pluralistic Islam (see my essay) and in autonomous consensus (see my essay). This means that while I respect Barlas and Finn’s particular interpretation of the hijab verses for themselves, I reject any suggestion that this interpretation is any more valid or authoritative than the common interpretation of believing women themselves of these verses–who believe that the verses require the hijab even in the modern world. True feminism requires that you respect the personhood of each woman, and that means respecting them even when they partake in their civilization in a way that you do not like. She is as much a human as you are and you have no right to force your views on her. Barlas and Finn do say that some women wear the hijab as a personal choice for modesty. But it seems that they only consider this a valid choice if it comes out of a person’s personal desire rather than out of their adherence to the classical interpretation of the hijab verses.

In other words, the two of them are not pluralists. They believe ignoring the hijab verses is the only correct interpretation and, if I am not mistaken, they deny the majority of Muslim women the right to interpret the verses in the classical way.

Regarding the famous “wife-beating” verse of 4:34 which establishes the concept of qiwāma (men being in charge of their households), they write:

Many Arabic-English versions mistranslate the key word, qawwamun, then use that to explicitly claim that the verse asserts male privilege: "Men are in charge of women," "Men are protectors," "Men are the managers of the affairs of women," "Men are superior to [women]." Both "maintainers" and "breadwinners" are by all accounts warranted by the Arabic meaning of the word qawwamun. Male privilege, however, is neither suggested nor implied. So how was that conclusion reached?

This is a rather weak line of argumentation. As I discuss in my detailed analysis of verse 4:34 and the issue of wife-beating, the word qawwāmūn is inescapably related to command and being in charge, as one of the earliest exegetes of the Quran, the Prophet’s Companion Ibn ʿAbbās, says. What makes it inescapable is that the verse clearly states that God has given men a “superiority in rank” to women and goes from mentioning qawwāmūn to mentioning the issue of discipline. If this word was merely about men being bread-winners, then it is rather silly to mention (1) a superiority in rank and (2) suddenly switch mid-verse to the issue of discipline. But if the word has to do with authority in the household as all classical exegetes agree, then it makes perfect sense that the issue of discipline would immediately come up.

Their denial of the classical interpretation of this verse therefore requires breathtaking leaps of logic–it is almost as incredible as arguing that the color black is actually white and that it has been only considered black due to a patriarchal conspiracy. The feminist author Amina Wadud recognized the weakness of this line of argumentation and abandoned her efforts to reinterpret them.

Barlas and Finn are unable to come up with any interpretation of verse 4:34 that preserves the ordinary meaning of wa-ḍribūhunna (“and strike them”) that does not encourage violence against women, and for this reason they are forced to use the unconvincing argument that this word is not being used to mean striking. Again, in the free market of ideas that Islam should be, people should be free to understand the Quran on their own terms. And it would be no surprise if history continues to support the classical reading, since it is so obvious and convincing. As for how wife-beating could ever be a thing in a civilized and self-respecting society, I discuss it in detail in my essay on the verse. The short of it is that after establishing men’s authority in the household, the Quran needs to give men the power to enforce this authority (authority without enforcement power is largely useless), and very similar to the way the police is given the right to use violence in extreme circumstances, men too are given this “policing right”. Please read the full essay where I discuss how this does not lead to a reign of terror of the husbands, just as in a well-functioning society the police never have to use violence. If a man’s violence against his wife is unjust, unjustified and abusive, then that is punishable by the Islamic law of scholars like Ibn Ḥazm.

I agree with Amina Wadud that wife-beating has no place among self-respecting and mature adults. This is beyond doubt. Wife-beating should be considered absurd and taboo by the average Muslim. But as I discuss in the essay, the verse has nothing to do with well-functioning, middle class marriages. Verse 4:34 continued to give me trouble until recently when I realized it was about law-enforcement and social order. Please read the essay for the details.

Get it on Amazon

It may be asked how could a man respect his wife as an equal if he is given “authority” in his household? It is similar to the way a project manager respects his colleagues who work under him as equals. He does not treat them as inferior humans, he knows that he has been given authority by the higher ups in order for the enterprise to function properly. In the same way, a man is entrusted with authority by God in order for the household to function properly. Why is it given to men and not women? The answer is that because men and women are different.

See the recent book Evolution’s Empress: Darwinian Perspectives on the Nature of Women which was published by Oxford University Press. The book covers the theories of the great feminist anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy in detail. There are important differences between males and females in all primates, including humans, both in physical and psychological traits. God’s justification for giving men authority over women must have something to do with these traits.

I am aware that pseudoscientific arguments have often been abused by some of the religious to justify low opinions about women (they are emotional, etc.). I do not in anyway suggest that science conclusively shows that patriarchal family organization is the best. What I argue is that science shows that there are clear differences between men and women, therefore it is not entirely implausible that such differences can be the basis for different roles in the family. Much further scientific research will be needed to show the correctness or falsity of this assertion. Is I have stated, from God’s perspective, men and women are already equal partakers in civilization. By giving men authority over women, God’s purpose is for families to function better. So the scientific question is this: do devout Muslim families that respect this authority function better than other families or not? Is there more happiness or less? Is there more dysfunction, drug abuse and depression in such families or in others? Detailed and unbiased scientific studies would be required to test the full effects of this patriarchal social organization. My contention is that giving men authority in the household leads to objectively better results for everyone involved, including women. It is the final results, the objective effects, that matter here, rather than theoretical discussions about whether this is fair or unfair.

If a woman is made happier by her husband being in charge of the household, what right do you have to take this away from her? Should you not respect her as a person to choose for herself what she is most happy with? If 99% or 90% of devout Muslim women are perfectly happy with men being authorities in the household, what right do you have to attack them for this? It is highly misogynistic to think that all of these women are somehow brainwashed or like herd animals incapable of thinking for themselves–unfortunately a very common, elitist feminist worldview.

The book deals with the issue of two women witnesses’ testimonies being equal to one man’s. This is not a matter I have studied deeply so I do not have much to say about it. I believe that the only thing that would settle the debate in this case is unbiased and detailed scientific studies that show how men and women differ in their accuracy as witnesses. If they are shown to be equal, then this can help us interpret the verse’s meaning better. And if it shown that women and men differ, then those differences should be taken into account.

Get it on Amazon

The writers attack the Islamic toleration for polygyny (having multiple wives), apparently believing that this is inherently unjust to women. But as A.S. Amin shows in his book Conflicts of Fitness: Islam, America, and Evolutionary Psychology, there are strong arguments for polygyny actually improving women’s status and well-being. Again, if two consenting female adults agree to be wives to the same man, and if we respect each female as an infinitely respected person, then we should leave it to themselves to make the choice. Polygyny is somewhat taboo in perhaps all middle class, cosmopolitan Muslim societies, and I consider that a good thing since I do not like men making their wives unhappy by finding new (often younger) wives to be their competitors. But there are cases where it is beneficial, so if a society is properly well-educated and cosmopolitan, we can trust the men and women to make the appropriate choices in most cases.

Believing Women in Islam ends with a discussion of the issues inherent in interpreting the Quran. The book is a good summary of the latest feminist arguments against various unjust practices against women, although it offers nothing new as far as I could find compared to other feminist works like the 2015 book Men in Charge?. Its attacks on concepts like the hijab and qiwāma are likely to prove futile since it is unlikely that most devout Muslim women would find their arguments convincing. It will likely give hope to women already avoiding the hijab and living somewhat feminist lifestyles that their way of life is not entirely invalid in Islamic terms (whether such hope is justified or not is another issue). But when it comes to the Muslim community as a whole, we can expect it to continue just as before–slowly improving its treatment of women as its appreciation for humanist ideals like personhood improves, while continuing to hold onto the plain meaning of the Quranic directives.

The Islamic cure for nihilism

Is Iran a truly Islamic government?

Dealing with Sufism making you feel arrogant and superior

The Cambridge Companion to Classical Islamic Theology by Tim Winter

Get it on Amazon

The Cambridge Companion to Classical Islamic Theology is a good introduction to the topic of Islamic theology and its relationship with Sufism. It was edited by Timothy Winter, known to Muslims as Shaykh Abd al-Hakim Murad. The essays are by many well-known and highly respected scholars, such as Shaykh Umar Faruq Abd-Allah and Yahya Michot.

The essays are mostly introductions to their topics and do not delve too deeply into the details. In fact many of them end right when things seemed to start to get interesting to me, for example Steffen A. J. Stelzer’s highly interesting chapter on ethics.

The book could have as well been titled An Introduction to Islamic Theology. This makes it different from other Cambridge Companions I have read where scholars delve deeply and present new interpretations and theories of their own. Here the scholars almost entirely limit themselves to presenting overviews of the topics they discuss, which is beneficial for beginners to the topic, but not so beneficial for those wishing for detailed discussions.

The two exceptions are Steffen A. J. Stelzer’s essay on ethics and Toby Mayer’s essay on theology and Sufism, which present new and interesting analysis.

The History of Salafism: The Making of Salafism by Henri Lauzière

Henri Lauzière’s 2016 book The Making of Salafism is about how Salafism as we know it today was invented in the 20th century. I discovered Lauzière’s work through reading his 2010 article “The Construction of Salafiyya: Reconsidering Salafism from the Perspective of Conceptual History,” in the International Journal of Middle East Studies. That article overturned many of my assumptions about Salafism that are commonly repeated today by Muslim intellectuals: that it somehow started with Muhammad Abduh (1849 – 1905) and that later on it was “stolen” by Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabis.

Lauzière 2010 article presents convincing evidence that Muhammad Abduh never considered himself a “Salafi”, and that the people who originally used the “Salafi” epithet did not usually have today’s Salafism in mind. On the one hand there were scholars like the Syrian Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qāsimī (1866 – 1914) and the Iraqi Maḥmūd Shukrī al-Ālūsī (d. 1924) who stood for modernism, criticized the Wahhabis, and considered themselves a followers of theological Salafism, which Western scholars today call Traditionalism.

This school of thought took its inspiration from Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal (known reverentially as Imam Aḥmad) and among its followers are the imams al-Bukhārī and Muslim and many of the best known members of the Shāfiʿī and Ḥanbalī schools: Abū Ḥāmid al-Isfarāʾīnī (Shāfiʿī), Abū Isḥāq al-Shīrazī (Shāfiʿī), Ibn al-Jawzī (Ḥanbalī), Ibn Ṣalāḥ al-Shāhrazūrī (Shāfiʿī), Imam al-Nawawī (Shāfiʿī), Shams al-Dīn al-Dhahabī (Shāfiʿī), Ibn Taymīya (Ḥanbalī) and Ibn al-Qayyim (Ḥanbalī).

This theological Salafism is nothing new within Islam, it is in fact one of the oldest intellectual strains within it and, unlike today’s Salafism, was never a challenger to the madhhabs (schools of thought).

In parallel to such theological Salafis, a Salafiyya Bookstore was established in Cairo by Muḥib al-Dīn al-Khaṭīb (d. 1969) and Abd al-Fattāḥ Qatlān (d. 1939). It is clear from the activity of this bookstore that they did not have today’s Salafism in mind either when they used the “Salafi” title, whether in naming their bookstore or their magazine. They published books by philosophers like al-Farabi and were highly modernist in their thinking. “Salafism” to them was the use of Islam’s ancient heritage (including philosophy and kalām, disliked Islamic fields of study according to today’s Salafis) in order to promote a sense of hope and pride among the colonized Muslims of the time.

At this point Rashid Rida (1865 – 1935), a disciple of Muhammad Abduh, comes on the scene to promote his vision of Islamic reform. While at first he continued to promote Muhammad Abduh’s teachings, in the 1920’s he started to increasingly describe himself and his movement as “Salafi”. For him, claiming to be “Salafi” was a way of breaking away from the traditional schools of thought without being called a deviant or liberal. By claiming to follow a version of Islam even more authentic and original than the version followed by the scholars of his day, he could break away while maintaining his credentials as a respectable Muslim thinker.

Things changed with the establishment of the Saudi state and their conquest of Mecca and Medina in 1924. Rashid Rida considered the Saudi state the only viable successor state to the Ottomans and apparently put all of his hopes in them. He started to defend the Wahhabis and their actions, apparently thinking that their ways of thought could eventually be softened and modernized (he was quite wrong).

With the establishment of the Saudi state, the Salafiyya Bookstore largely abandoned its modernist tendencies. With the involvement of Rida, a Salafiyya Press and Bookstore was established in Mecca in 1927 that was little more than a Wahhabi propaganda press, printing works like Ibn Bishr’s pro-Wahhabi History of Najd, in which the slaughter of thousands of innocent Iraqi civilians is proclaimed as a great victory (the 1801 Wahhabi sack of Karbala). I recently saw a quotation from Saudi Arabia’s founder Ibn Saud (1871 – 1953) saying that not only was he not sorry that the Wahhabis had engaged in that massacre, but that he would happily do it all over again if he had the chance. This explains Winston Churchill’s opinion of him:

The British recognised Ibn Saud's control of Arabia, and by 1922 his subsidy was raised to 100,000 a year by Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill. At the same time, Churchill described Ibn Saud's Wahhabis as akin to the present-day Taliban, telling the House of Commons in July 1921 that they were 'austere, intolerant, well-armed and bloodthirsty' and that 'they hold it as an article of duty, as well as faith, to kill all who do not share their opinions and to make slaves of their wives and children. Women have been put to death in Wahhabi villages for simply appearing in the streets. It is a penal offence to wear a silk garment. Men have been killed for smoking a cigarette.'

However, Churchill also later wrote that 'my admiration for him [Ibn Saud] was deep, because of his unfailing loyalty to us', and the British government set about consolidating its grip on this loyalty. In 1917 London had dispatched Harry St John Philby--father of Kim, the later Soviet spy--to Saudi Arabia, where he remained until Ibn Saudi's death in 1953. Philby's role was 'to consult with the Foreign Office over ways to consolidate the rule and extend the influence' of Ibn Said. A 1927 treaty ceded control of the country's foreign affairs to Britain.

Professor Mark Curtis, Secret Affairs: Britain's Collusion with Radical Islam

Throughout this time, there was no such thing as “Salafism” the way we understand it today. Salafism was a fluid and largely undefined concept that started as a movement to promote the greatness of the ancients of the Islamic world as a way of fighting off the cultural influence of the West.

Rashid Rida became increasingly pro-Wahhabi and did everything in his power to support the Saudi state, most importantly sending his own disciples to work in the Saudi educational establishment in the Hijaz. The people of Mecca and Medina had no love for the Wahhabis and considered them backward and ill-educated, while they respected Egyptian scholars and intellectuals.

Rashid Rida never became a Wahhabi himself. He continued to maintain his reformist views that the Wahhabis had no interest in while also continuing to write apologetics in support of the Wahhabis.

The Making of Salafism

That brings us to Lauzière’s 2016 book The Making of Salafism: Islamic Reform in the Twentieth Century. This monograph expands on the 2010 article but adds a major new element with its focus on the career of Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din al-Hilali, the Western-educated Moroccon Sufi who became a modernist reformist and disciple of Rashid Rida only to become increasingly Wahhabized over the decades until he became one of the best known figures of the international Wahhabi mission.

Lauzière starts with a discussion of the fact that “Salafism” as we understand it today was completely non-existent before the 20th century. Salafi claims about the existence of a “Salafi” doctrine in the works of great scholars like Ibn Taymiyya are misplaced (although I believe seeds for today’s Salafism do exist in his writings–for example in his refusal to be called a Ḥanbalī, wherein he refused to be defined by madhhab boundaries similar to today’s Salafis). Salafism to them was the well-known Traditionalism I mentioned earlier; it simply meant to refuse to engage in philosophical speculation about the nature of God. It was in no shape or form a worldview that defined everything, nor was it a competitor to the traditional madhhabs. As late as the first two decades of the 20th century, we have textual evidence from Nuʿmān al-Ālūsī, Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qāsimī and Muhammad Abduh using “Salafism” to refer only to theological Salafism. Later Rida tried to claim that Abduh was a Salafi in the modern sense, but the complete lack of evidence to that, and evidence to its contrary, show that this was just an effort to revise history.

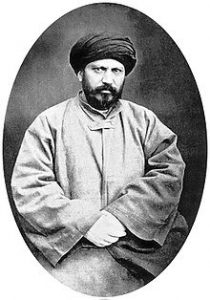

A comical misunderstanding

The great French Orientalist Louis Massignon (1883 – 1962) was in contact with Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qāsimī and other scholars and was receiving a magazine published by the Salafiyya Bookstore. In a 1925 paper, Massignon tried to make sense of this new “Salafi” movement and attributed it to Muhammad Abduh and his mentor Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838 – 1897). He considered it a reformist and modernist movement founded by these two scholars. This myth of a “reformist Salafism” that continues to be repeated today appears to have originated here with Massignon.

ʿAllāl al-Fāsī (1910 – 1974), a Moroccan political activist and religious intellectual, appears to have been inspired by Massignon’s writings on Salafism so that he took it up, later becoming one of the main representatives of “modernist Salafism”, which he believed had started with al-Afghani and Abduh.

This reformist Salafism was everything Massignon thought it was: a movement of religious intellectuals who admired the West, desired reform and wished to restore the glory days of Islamic civilization. Later Westerners who tried to study Salafism really believed that Salafism had started as a reformist movement because they knew of prominent people like al-Fāsī who called themselves Salafis.

The reality, of course, was that al-Fāsī had been misled by Massignon’s erroneous writings about the existence of a modernist movement named Salafism into adopting that form of Islam.

Therefore the idea that Salafism was “hijacked” by the Wahhabis, as Khaled Abou El-Fadl states in a 2001 article, is incorrect because there was no Salafism at the time to be hijacked. There was one group that called itself Salafi but used it only in the theological sense, as al-Qāsimī did. There was also a modernist group, the Moroccan Salafis, who had taken up the “Salafi” epithet based on Massignon’s writings. There was also Rida, who started to take up the “Salafi” label in the 1920’s despite having no clear idea what exactly it had to mean. He considered the Wahhabis the Islamic world’s best hope for fighting colonialism and therefore defended them despite his misgivings about their beliefs and actions and sometimes wrote absurd articles in which he portrayed the Wahhabis as not so different from the modernist readers of his journal al-Manar.

Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din al-Hilali

Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din al-Hilali (1893 – 1987) is best known in the West for the Saudi-sponsored translation of the Quran known as The Noble Quran, which was written by Muhammad Muhsin Khan and al-Hilali, sometimes referred to as the Hilali-Khan translation. Al-Hilali’s career is a good representation of how Salafism became the Salafism we know today. Al-Hilali’s career is one of the central themes of Lauzière’s book.

Al-Hilali was originally a Sufi of the Tijaniyya order. In explaining his abandonment of Sufism, al-Hilali claimed that at one point (in the late 1910’s perhaps or early 1920’s), while praying on a cold night in the desert, he had a vision of the Prophet Muhammad PBUH in which the Prophet instructed him to study religious science. When al-Hilali asked him whether to study bātin science (mysticism) or ẓāhir (non-mysticism-related Islamic studies), the Prophet says to study the ẓāhir.

Al-Hilali arrived in Egypt in 1922 and soon became a student of Rashid Rida. Later he traveled to India and Iraq. As part of the support of Rida and his disciples for the Saudi state, al-Hilali was invited to work as a teacher in the Saudi educational establishment in 1927. He became faculty supervisor at the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina.

At this time al-Hilali was extremely anti-Sufi and considered Sufism an evil and corrupt doctrine. When he discovered that one of the professors at the Prophet’s Mosque was a Sufi (Alfa Hashim), he wrote an anti-Sufi polemic and gave it to a Wahhabi judge, requesting that Hashim be fired. Hashim, in order to absolve himself from al-Hilali’s accusations, was made to write an anti-Sufi tract in which he condemned various doctrines of the Tijaniyya order.

When a Wahhabi scholar Ibn Bulayhid (d. 1940) discovered that al-Hilali was teaching that the earth is round, he made a big fuss and called it a bidʿa (heretical innovation), saying that the proper Islamic doctrine is that the earth is flat. He ordered al-Hilali and Hamza (another Egyptian and Rida disciple) to repent. The rest of the Wahhabi faculty started to treat the two of them as deviants and heretics. Al-Hilali managed to find supporting evidence from Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn al-Qayyim’s writings on the earth being round, which made Ibn Bulayhid calm down, although he never admitted to having erred. Rida had to assure his readers in al-Manar that not all Wahhabis believe that the earth is flat.

Decades later, al-Hilali voiced support for Ibn Baz’s fatwa in which Ibn Baz declared that (a) the earth is flat and (b) anyone who disagrees with that can be put to death. Al-Hilali spoke French, had spent years in Europe and was very familiar was Western science (and early in his career worked to promote it). It seems unlikely that he would have really accepted the earth’s flatness, therefore his support for Ibn Baz’s fatwa appears to have been nothing but an effort to ingratiate himself with this all-important Saudi religious authority. It is, however, not impossible that later in his life he became so Wahhabized that he could convince himself to prefer Wahhabi “truths” to mere scientific truths.

In 1927 Rida had changed his moderate reformist tone so that he start to publish anti-Shia articles by al-Hilali. Rida had hoped that his disciples could spread his ideals of balanced reform among the Wahhabis. But quite the opposite happened. In their eagerness to fit in within the Saudi establishment, nearly all his disciples became increasingly Wahhabized.

Between 1930 and 1950 al-Hilali lead a double public life. On the one hand, he supported anti-colonial efforts among all Muslims without caring too much about how deviant their religious doctrines were according to Wahhabi standards. On the other hand, he continued to publish polemics in Wahhabi journals against various Muslim groups he accused of deviance and unbelief. Thus while he was increasingly becoming a Wahhabi purist, he continued to hold onto his ideals for reform and adopted tolerant attitudes toward certain “deviant” Muslim groups when he considered it beneficial to do so, something authentic (Najdi) Wahhabis would have never done.

Al-Hilali returned to Morocco at the end of his life, being paid by the Saudi state to continue spreading Wahhabism. From the 1970’s onwards Salafism slowly crystallized into what we know today, largely due to Wahhabi influence. Many individuals came on the scene to define a “Salafi method” for judging legal and theological issues outside the madhhabs. In his conclusion, Lauzière states:

The idea of a distinctive Sunni methodology applicable to Islamic theology, law, and virtually all other aspects of the religious and human experience was itself untraditional. Therefore, the purist version of Salafism should not be understood as a medieval or early modern concept or movement. To say that it dates from the time of Ibn Taymiyya or Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab not only is anachronistic but also obfuscates the development of modern Islamic thought. Although many of the ingredients of purist Salafism are old, the recipe and the final product (including the term Salafism) are not.

The Making of Salafism is an admirable work of scholarship–thorough and balanced. I looked forward to reading Henri Lauzière’s future works.

If God loves us, why does He allow us to suffer?

Is it permitted to sing in the shower/bathroom?

Can you make wudu when your awra is visible?

How do I balance between being a programmer and a writer?

Was Abu Talib a Muslim?

How to get up for fajr prayer when you keep falling asleep after the alarm

Should you tell your fiance about your hymenoplasty?

If God is responsible for guidance, why are humans punished for being misguided?

The evidence for the permissibly of drawing and painting in Islam

What to do if you cannot pray on time at school or work

Does bleeding from the gum nullify wudu or fast?

The Crucible of Islam by G. W. Bowersock

Get it on Amazon

G. W. Bowersock’s 2017 book The Crucible of Islam is a very brief survey of the religious and political situation of Arabia in the centuries leading up to the coming of Islam. There is mention of the relationship of the Byzantines, Persians and Ethiopians with the Jews and Christians of Yemen and Arabia.

The purpose of the book is to shed light on the “crucible” in which Islam was made. Due to the extreme lack of documentary evidence on the situation in Mecca and its surroundings, the book is restricted to retelling the stories of a few major events in the surroundings that may (or may) not have had an important influence in the way Islam came about. The Ethiopians conquered Yemen and Christianized it. The Persians and Byzantines competed for influence over the region through their relationships with allied Arab tribes. I cannot really say that much light has been shed on the crucible of Islam; due to its briefness and the lack of documentary evidence, the book serves mostly to show how little we know about the reality of the facts on the ground.

The most interesting thing I learned from this book is Michael Lecker’s theory that the Ghassanids in Medina may have had a role in encouraging the Jews and pagans to unite under the rule the Prophet Muhammad PBUH. The Byzantine emperor Heraclius may have encouraged his clients the Ghassanids to do this in order to ensure that the Persians did not regain influence over the Medina region.

Below are some notes on (mostly minor) issues and errors that I encountered in my reading.

On page 39 he says there are no daughters of Allah mentioned in the Quran. While it is true that no daughters of Allah are mentioned by name, the Quran does contain mention of the pagans attributing daughters to Allah:

And they attribute to God daughters—exalted is He—and for themselves what they desire. (The Quran, verse 16:57)

Ask them, “Are the daughters for your Lord, while for them the sons?” (The Quran, verse 37:149)

Or for Him the daughters, and for you the sons? (The Quran, verse 52:39)

He considers the Wars of Apostasy an inappropriate label because he assumes they were majorly aimed at false prophets like Musaylama. But according to Muslim sources these wars were aimed first at tribes that refused to pay the zakat which they had paid during the time of the Prophet PBUH. The war on Musaylama was a sequel to these, and rather than being directed at extinguishing a rival religion specifically, the war was an act of statecraft; Musaylama had established a state that was at war with the Muslim state, and the Muslim state responded.

He mentions the word ukhdūd as referring to the Trenches in the Battle of the Trench, even though the name universally used is khandaq. He mentions that chapter 85 of the Quran al-Burūj commemorates this battle when there is no relationship between the chapter and the battle whatsoever. This chapter in fact commemorates that killing of Christians by Yemeni Jews, a chapter of pre-Islamic history that Bowersock himself mentions often. The chapter of Quran the actually commemorates the Battle of the Trench is chapter 33, al-Aḥzāb (“The Confederates”).

He mentions that the relics of the True Cross had been moved to Baghdad in 614, possibly meaning al-Madāʾin because Baghdad did not exist at the time.

He says that the Prophet’s cousin ʿAlī b. Abū Ṭalib did not belong to the Quraysh tribe but to the Banū Hāshim, confusing clan differences with tribal differences. Banū Hāshim were actually a clan within Quraysh.

He mentions that the Prophet PBUH “reconstructed” the Kaʿba. The phrasing implies that he did this as part of his mission. There is no evidence as far as I know that the Prophet PBUH made any changes to the Kaʿba. He had taken part in repairs to the Kaʿba before he became a prophet.

His treatment of the Dome of the Rock seems to suggest that he is unaware that the mosque (al-Masjid al-Aqṣā) is actually the original mosque that was established on the Mount. He expects the traveler Arculf to have seen the rock in the mosque, but since the mosque does not actually include the rock and is hundreds of meters away from it, it is quite natural that Arculf does not mention the rock. The Dome of the Rock itself is not a mosque but merely a shrine.