Distinguishing between trustworthy and untrustworthy Muslim scholars and intellectuals

On raising the hands during salah as a Hanafi

On the Shia and their fate according to Sunni Islam

A Traditionalist Critique of the Islamic Prohibition on Taṣwīr (Making Drawings and Statues of Humans and Animals)

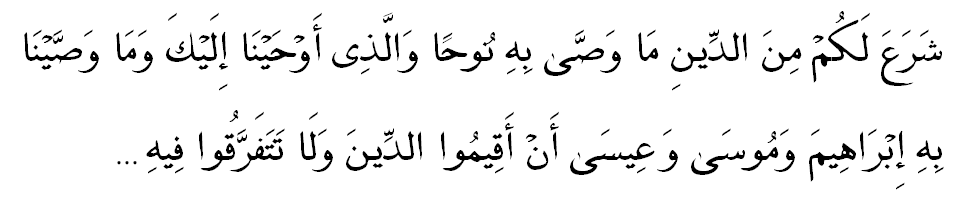

A Caravan with the Pyramids and Sphinx Beyond (Joseph Austin Benwell , 1868)

To many Muslims today, it will sound patently absurd if someone were to tell them that it is a mortal sin for them to draw a cat. But some religious scholars would tell you that drawing a cat is an act of taṣwīr (the depiction of living things in paintings, sculptures and elsewhere), a sin for which God supposedly promises the severest punishment.

Mainstream Sunni Muslims today follow the opinions of popular religious scholars like Muhammad al-Ghazali, Yusuf al-Qaradawi and Ali Gomaa, who by and large have no issue with drawings and statues. Since neither Muslims nor their respected scholars have an issue with taṣwīr, it is largely a theoretical issue within Islamic law. There is, however, a minority of puritan Muslims, especially on the internet, who often bring up this issue, claim that a severe and even violent distaste for taṣwīr is the proper Islamic stance, and who categorically reject the opinions of mainstream scholars like al-Ghazali, al-Qaradawi and Gomaa.

This article seeks to answer the needs of Traditionalist-minded Muslims on the matter of drawings and statues. Below I translate an Arabic article I discovered a few years ago by a well-informed Traditionalist author who criticizes the supposed prohibition on taṣwīr. This article is significant because when even such a Muslim can find good reasons to doubt the prohibition on taṣwīr, this acts as supporting evidence for the mainstream Islamic practice of tolerating it. The author is an anonymous user of the Traditionalist internet forum Multaqā Ahl al-Ḥadīth (The Meeting Place of the Traditionalists) who goes by the name of al-Shaykh Muḥammad ibn Amīn.

The author’s notes are in parentheses, while translator’s notes are in square brackets. I use the word “statue” to translate timthāl, a catch-all term for all statues, sculptures, effigies, murals and other three-dimensional figures depicting humans and animals. I use the word picture, painting, image and figure mostly interchangeably, choosing one over the other depending on the context.1

Beginning of Translated Article

Ḥukm al-Ṣuwar wa-l-Tamāthīl – The Islamic Ruling Regarding Pictures and Statues

Praise be to God. There has long been a legal theoretic issue of dispute, in fact since the time of the Companions, and that issue is this: Do we enact the literal meaning of a text or do we enact its spirit? Meaning, do we apply the text in its literal and apparent sense, or do we try to understand its spirit and rationale? The Companions differed on this. You are probably aware of the hadith on the ʿaṣr prayer in the Banī Qurayẓa affair. Some of the Companion understood [the Prophet’s instructions PBUH] in their apparent form, while others tried to understand the purpose behind the instructions. The Prophet PBUH approved of the actions of both groups.

The issue [surrounding drawings and statues] is confused because there are texts mentioning instructions regarding the destruction of statues and the obliteration of pictures. Those who take these texts in their literal meaning would consider it obligatory to destroy every statue and obliterate every picture. Most of them [those who take the texts literally] consider photographic pictures permissible because they are merely the capturing of projections of light. And whoever prohibits this falls into contradiction since he is bringing together two mutually exclusive views.2

The other opinion is that the reason for the prohibition of pictures and statues was to prevent them from becoming means of shirk [assigning divine powers to other than God] or tabarruk [considering an object a source of blessings]. Forbidding statues does not require that they should be worshiped. If they are regarded with veneration by people, then this is sufficient to prohibit them in order to prevent this veneration from developing into worship. For this reason many of the ulema [scholars] consider it permissible to place pictures in debased places. It is permissible [in their opinion] for a rug to have pictures on it since it is stepped on by people, preventing the pictures from being venerated. It is also permissible to create statues without heads, since this makes them appear deficient. And it is also permissible to place a picture in a place where it cannot be viewed. It is not permissible to place a picture (photographic or drawn) on a wall, but it is permissible to place it between the pages of a book if one can be sure that the picture is not venerated (for example if it is not the picture of a sheikh or wali). The majority permitted pictures of living things that do not have rūḥ [soul or spirit], such as plants and nature. There are even those who permitted the creation of statues and pictures if it was certain that they would not be venerated. Al-Qirāfī [a Mālikī legal theorist of the seventh century of the hijra] used to make statues himself, as he mentioned in his book Sharḥ al-Maḥṣūr.

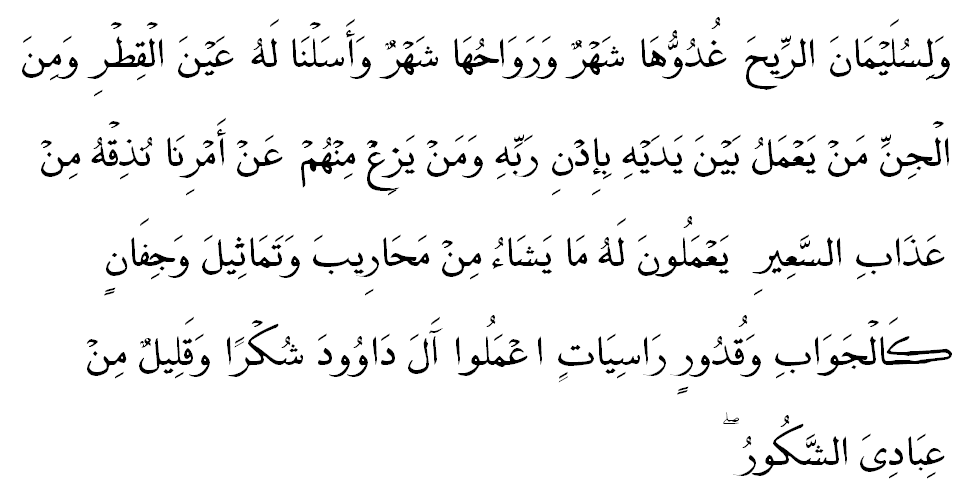

Two types of statues are mentioned in the Book of God [the Quran]: The first type are those statues that are worshiped instead of God. These are called tamāthīl, aṣnām and anṣāb. It is obvious for us to say that these types of statues are prohibited for a Muslim to create or buy, since in such an act would be an aid in shirk. The second type are those statues that are not worshiped instead of God, such statues are not aṣnām or anṣāb. The Quran, in fact, mentions the creation of statues as one of the blessings that God bestowed upon Solomon [as]:

12. And for Solomon the wind—its outward journey was one month, and its return journey was one month. And We made a spring of tar flow for him. And there were sprites that worked under him, by the leave of his Lord. But whoever of them swerved from Our command, We make him taste of the punishment of the Inferno. 13. They made for him whatever he wished: sanctuaries, statues, bowls like pools, and heavy cauldrons. “O House of David, work with appreciation,” but a few of My servants are appreciative.3

Here, God refers to statues as timthāl-s [statues] rather than aṣnām [idols], since they were not meant to be worshiped in God’s stead. This matter has to do with monotheism and faith and is a shared doctrine among all of the Prophets. There is no disagreement among the ulema that when it comes to the ʿaqāʾid [plural of ʿaqīda, beliefs regarding the nature of God and other matters] have not undergone change and that they have always been one and the same among the Prophets, for God says:

He prescribed for you the same religion He enjoined upon Noah, and what We inspired to you, and what We enjoined upon Abraham, and Moses, and Jesus: “You shall uphold the religion, and be not divided therein.” ...4

Many authentic hadith narrations exist that insist that the muṣawwirīn [figure-makers] are in the Hellfire, and that they will be among those who suffer the severest punishment. The reason for their punishment according to the texts of the hadith narrations is that they imitate God’s creation, and muḍāhāt [the sin the texts accuse them of] is the same as mushākala [the creation of the likeness of something], meaning that they create sculptures in the likeness of God’s creation, so that on the Day of Judgment they are told: “Bring to life what you have created!” Al-Nawawī5 says in his Commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (14/84): “They [i.e. the ulema] agreed on prohibiting all [figures] that have shadows and on the necessity of changing them.” But Ibn Ḥajar6 adds in al-Fatḥ [his commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī] (10/388): “This consensus does not include children’s toys.”

There is conclusive evidence that the Prophet PBUH used pillows and utensils that had pictures on them, but he used to remove and wipe out pictures of crosses. It is also proven that he permitted children’s toys in the form of small statues/dolls, as is narrated from the Mother of the Believers Aisha, may God be pleased with her. Qaḍī ʿIyāḍ7 mentions that the majority of jurists permitted buying these dolls for the training of girls in matters pertaining to childcare, which is recognized as a worthy aim in Islamic law. While his information is correct regarding the permissibility of dolls, his reasoning is incorrect, since Aisha mentions a horse that had two wings; what relationship does that have with children’s education? The correct opinion is that children’s playthings are permissible for males and females without any karāha (legal disapproval), since they [dolls] are far away from the potential for veneration. One of our teachers used to say: “Children’s wisdom is greater than that of many adults, for you never find a child worshiping the doll he or she plays with.”

But if statues are an imitation of God’s creations, or creating their likeness, then that makes them forbidden and is considered a mortal sin according to the authentic narrations on the matter. But creating a likeness of God’s creations or imitating them could be done through making sculptures of soulless things like the sun, the moon, mountains and trees, and through making girls’ dolls and similar things that the texts explicitly permit. For this reason some of the ulema say that what is intended are those who create statues or make pictures with the aim of challenging God’s power, or those who think that they have a similar power to create as God has. God shows such people their incapacity by asking them to bring life to what they create. In support of this, Ibn Ḥajar, in al-Fatḥ al-Bārī [his aforementioned commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī], regarding God’s saying in His ḥadīth qudsī: “And who is greater in injustice than one who goes in order to create a creature like My creation?” interprets “goes” here to mean “aims”. According to this, the forbidden thing here is related to the intention of the maker [of the statue, etc.], whether the product is a statue or a hand-drawing of any image. It is mentioned in the Mawsūʿa al-Fiqhīya [The Encyclopedia of Islamic Jurisprudence, a 45-volume work by Kuwait’s Awqāf ministry including opinions from all of the four schools of Islamic jurisprudence, completed in 2005 after 40 years of work], in Bāb al-Taṣwīr [the chapter on figure-making]:

The majority of ulema agree that prohibiting figures does not imply a prohibition on possessing them or using them, for regarding the process of making figures of things that have souls, it is mentioned that figure-makers are cursed and that they will be punished in the Hellfire and that they will be among the most severely punished among the people, but nothing is mentioned regarding possessing pictures, and there is no accepted evidence for the existence of a reason for prohibiting the user of such figures. Despite that, there are narrations that prohibit the possession and use of pictures, but they do not mention a punishment or equivalent that imply that possessing figures is a mortal sin. For these reasons, the judgment regarding the possessor of pictures whose possession is forbidden is that they have committed a small sin... Among those who were aware of the difference between figure-making and the [mere] possession of figures were: al-Nawawī... and most of the jurists are in agreement with this.

As for narrations saying that the angels do not enter a house in which there is a figure or a dog, the likely intent are the angels of revelation and not others. For this reason Ibn Ḥibbān8 made this restricted to the Prophet PBUH, for the angels that are assigned to each individual would enter such houses, and God knows best.

The majority of the jurists have permitted the user of statues and pictures in houses if they are not placed on curtains or walls with the intent to view them with veneration, and if they are subject to debasement as in people stepping on them and so on. ʿIkrima9 says: “They used to dislike statues set up on pedestals, but they saw no issues with those which feet could step on.” ʿIkrima here is transmitting from [mentioning the opinion of] the Companions. Muḥammad ibn Sīrīn10 said: “They used to see figures that were spread out or stepped upon as different from those that were set up on pedestals.” Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr11 says in the Tamhīd (21/199): “This is the most balanced among the opinions and the most moderate in this matter and most of the ulema are in agreement with it. Whoever is fatigued with narrations [unclear meaning] will not oppose this interpretation. This is the best of what I believe about this matter. God is the helper toward the correct opinion.”

It appears that the permissibility of leaving alone figures and statues that are not venerated is the creed of the majority of the Companions, even their consensus. For they did not destroy statues and pictures in the countries of Persia, the Levant and Iraq, but they did so in India and the Arabian countries. That is because these things were not worshiped in Persia, the Levant and Egypt. They did not touch those enormous edifices and great numbers of statues which remain there to this day. Consider this anecdote:

Saʿd bin Abī Waqqāṣ (the conqueror of Iraq and one of those promised Paradise) [ra] entered the palace of Khosrow II in al-Madāʾin [Ctesiphon, the Persian capital, near modern-day Baghdad]. In that palace there were many figures on the walls and many statues. He did not destroy any of them, in fact they remain where they are to our day. None of the Companions criticized him or anyone else for this. This is a consensus from them regarding the permissibility of letting such things remain undestroyed if they are not worshiped in God’s stead and they are not ascribed holiness. Al-Tabarī says in his Tarīkh (2/464): “When Saʿd entered al-Madāʾin and saw its desertedness, and went to Khosrow’s hall, he went on to recite: “How many gardens and fountains did they leave behind? And plantations, and splendid buildings. And comforts they used to enjoy. So it was; and We passed it on to another people.”12 He performed ṣalāt al-fatḥ [ritual prayer performed after a conquest], which is not performed communally. He performed eight rakʿāt [units of prayer, plural of rakʿa] without pausing between them, and turned the hall into a masjid [mosque or prayer hall]. In it there were statues made of gypsum, of men and horses. Neither he nor the Muslims opposed their presence and left them where they were. It is said: Saʿd completed the prayer on the day he entered it, for he wanted to take residence in it [or take it as a seat of the new government]. The first Friday in which the Muslims gathered for Friday prayers in Iraq in al-Madāʾin was in the year 16 [of the hijra].” Also see the al-Dhahabi’s History of Islam (3/158).

In Khosrow’s hall there were colorful and life-sized pictures done in great detail. These pictures survive to our day. These pictures were, of course, not buried in the sand, rather, numerous companions entered this palace and stayed in it. How did they then not see the pictures which can be seen clearly to our day? Even if they were not able to destroy the pictures, they could have blotted them out through white-washing, and this does not require great expenses nor a large number of workers. It would have been easy for the ruling power to command that the walls be repainted. There is no other interpretation other than that they understood the hadith narrations regarding the destruction of figures as being specific to those which were accorded veneration or were worshiped in God’s stead. These pictures continued to be viewed, being described by historians and writers. Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī says in his Muʿjam al-Buldān [his famous geographical dictionary] (1/295): “In the hall there was Khosrow Anūshirvān picture, and that of Caesar king of Antioch, who was besieging it and fighting its people.”

The famous Abbasid poet al-Buḥturī describes them in his wonderful qaṣīda al-sīnīya [a type of ode]. He describes these pictures as having such detail that one could imagine them real, so that one would want to touch them to reassure themselves that they were mere pictures. He says in his ode:13

Sorrows attend my saddle. I direct

my stout she-camel to Madāʾin [Ctesiphon].

When you see a panel of the Battle at Antioch,

you tremble among Byzantines and Persians.

The Fates stand still, while Anūshirvān

leads the ranks onward under the banner

In a deep green robe over yellow.

It appears dyed in saffron.

The eye depicts them very much alive:

they have between them speechless signs.

My wonder about them boils till

my hand explores them with a touch.

The question here is: Why did the Companions let the pictures in Khosrow’s hall remain? Those who disagree with us are incapable of answering this. One of them says that we should only follow hadith and disregard the actions of the Companions. This is strange, for is it imaginable that the Companions would randomly follow their own inclinations? Aren’t the actions of the Companions and their sayings an interpretation and illustration of the teachings of the Prophet PBUH? We have not abandoned the Prophet’s sayings PBUH, and neither did the Companions, may God be pleased with them. Rather, they understood the texts in a way different from those who disagree with us. It is the Companions who narrated those hadith narrations to us. And it is they to whom those narrations were directed, therefore their understanding takes precedence in matters of dispute. And the ijmaʿ [consensus] of the Companions is one of the acknowledged sources of Islamic legislation. Additionally, all of the 73 groups claim to follow the Quran and the Sunnah, but the distinguishing characteristic of al-firqa al-nājiya [“the group that attains salvation”, i.e. from the hellfire]14 is that the group follows the Companions of the Prophet PBUH.

As for the claim that during all of those years they were too busy [to destroy the paintings and statues], I do not think the person saying that believes it himself, it is just that he cannot find a better argument. Was it too difficult for Saʿd bin Abī Waqqāṣ or one of the rulers after him to command one of the slaves to repaint those walls that had pictures? As for denying that the Companions had seen the pictures, this is obstinacy and denialism, for Khosrow’s hall is the biggest building in al-Madāʾin, and the fact of the Muslims entering it is a well-known and multiply-transferred piece of information that no one denies. It was full of pictures and statues and poems were written about it. This same hall became the center of government in Iraq until the building of the city of Kūfa was finished.

The sheikh Dr. Aḥmad al-Ghāmidī answered this criticism by saying: “These pictures and statues were not worshiped aṣnām, they were rather figures depicting past events, and perhaps there was a lesson or benefit in letting them remain.” I say that it might be so, and using the fact of their not being worshiped in his reasoning is the same as what I say. He also said: “Fifth, the prohibited thing is the creation of pictures. As for the narration from Ali, may God be pleased with him, regarding the destruction of figures, it refers to three-dimensional statues.” But they weren’t pictures only; the hall of Khosrow was full of statues as is the wont of kings. Ali himself ruled Iraq and did not order the destruction of any of its statues.

The mention of Khosrow’s palace is merely an example. In reality great statues have been allowed to remain not only in Khosrow’s palaces but in [the rest of] Iraq, the Levant, Egypt and Persia. Yes, certain worshiped statues were destroyed in Sindh [a province of modern-day Pakistan] and Transoxania when the Companions discovered peoples who worshiped them, as happened in the Arabian peninsula itself. But other than these, then no. A comical event was that one contemporary caller for the destruction of statues claimed that the Pharaonic statues had been buried in the sand and were not visible during the time of the Companions! Saying the in fact they hadn’t been seen until the past two hundred years. In this saying is negligence toward the books of history, for history books are full of information regarding the familiarity of Muslims with these statues. Al-Jāḥīẓ (who was a contemporary of the imams Mālik, al-Shafiʿī and Aḥmad) enumerated the wonders of the world, saying in his Ḥusn al-Muḥāḍara (3/65): “The ṣanam [statue of religious significance, singular of aṣnām] of the two pyramids is Balhawīya, also called Balhunayt [?] and called Abū l-Hawl by the common people. It is said that it is placed there as a talisman so that the sand would not overcome the Giza.” Yaqūt al-Ḥamawī in his Muʿjam al-Buldān (5/401) says: “On the corner of one of them (meaning the pyramids) there is a great ṣanam that is called Bulhayt [?]. It is said that it is a talisman for the sand so that it would not overcome the area of Giza. It depicts a human head and neck, and the top of its shoulders are like that of the lion. And it is very large. It has a pleasant appearance, as if its creator had recently completed it. It is painted a red color that survives to this day despite the great length of time and the distance of the years.” Also see the words of Ibn Faḍl in Masālik al-Abṣār (1/235) and the words of al-Baghdādī in al-Ifāda (p. 96).

The number of the Companions who entered Egypt was greater than three hundred, as al-Suyūṭī confirmed in Ḥusn al-Muḥāḍara (1/166). The first city they besieged was ʿAin Shams [today a suburb of Cairo] as is mentioned in Ibn Kathīr’s al-Bidāya wa-l-Nihāya (7/98). It is filled with large statues as ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādī mentioned in the sixth century [of the hijra], saying in his travelogue (p. 96): “Of that [type?] are the antiquities in ʿAin Shams. It is a small city the ruins of whose surrounding wall are visible, it appears that it was a place of worship. In it there are enormous statues carved from rock. The length of a statue is around thirty cubits, and its limbs are proportionally large. There is much writing on those rocks and figures of humans and animals of the unintelligible [ancient Egyptian] writing.” The Companions resided in al-Fusṭāṭ [today part of Cairo] and Giza, which are very close to the pyramids. It is worth mentioning that the pyramids themselves were covered in the language of the pharaohs, some of whose letters are in the shapes of birds and animals. Al-Baghdādī says about the pyramids (p. 92): “Upon those rocks there are writings in the unknown ancient pen, such that I did not find anyone in the towns of Egypt who knew of anyone who understood them. There is a great amount of these writings, such that if what is written was transmitted to pages of books, they would take up ten thousand pages.” Al-Masʿūdī mentions similar things in his history (1/361) and Ibn Taghrībirdī in al-Nujūm al-Zāhira (1/41).

Judging from all of that, the Companions who entered Egypt certainly saw the Sphinx and the pictures on the pyramids. These in addition to the statues in ʿAin Shams, about which there is no doubt that they saw them after its conquest and their entering the city. Denying that they saw them is obstinacy. These, in addition to the statues in the pharaonic cities of Memphis and others. It is more likely than not that they saw these too, due to the great number of the Companions and the length of their stay in Egypt. And it is these about which al-Baghdādī says (p. 102): “As for the statues, the greatness of their number and the enormity of their size, it is a matter that is beyond description and computation. The accuracy of their shapes, the meticulousness of their aspects and the carving upon them of natural facets is in truth a matter for wonder.” Despite that, we have not seen them [the Companions] destroy any of them. So were the Muslims incapable of destroying those statues? This is absolutely false. That is because they were able to destroy the fortress of Babylon and the walls of Nahavand in Persia, and they drilled through [the walls of] many of the fortresses they besieged, which were great fortresses that had armed guards that shot arrows at the Muslims during their drilling and destruction of them. Couldn’t they at least disfigure the faces of the statues? If this saying [that the Companions were unable to destroy the statues] is not an insult to the Companions then I do not know what is. Is it conceivable that non-Muslims were capable of building while the Muslims incapable of mere demolition? This is impossible.

To summarize, it is not permissible to hang any picture (including photographic pictures) if this has the potential of leading to veneration and the expectation of blessings from it (especially the pictures of sheikhs and leaders). But if one is safe from that (as in the case of one hanging his own picture or that of his child) then there is no issue with it. Any pictures that are in a place unlikely to be venerated, as on pillows and rugs, then there is no distaste for that. The same is true of statues. And there is no issue with children’s toys and dolls, for such things are not venerated. And if statues accomplish a benefit recognized by the Sharīʿa, such as for teaching or training (such as those used in schools for illustration and clarification), then they go from being mubāḥ [not forbidden] to mustaḥabb [recommended], they may even be wājib [strongly recommended or compulsory] in certain cases if they are a means of understanding the sciences and advancing in them. And God knows what the most correct opinion is.

End of the translated article

Translator’s Conclusion

It appears from the above discussion that one can conclude that the issue of taṣwīr is one of context. If a figure is accorded veneration for supposed metaphysical powers, it is prohibited to have it and use it. If it is not, then there is no issue with it. This means that the issue of taṣwīr is quite irrelevant to the lives of most educated Muslims, who find the idea of venerating a picture or statue absurd.

The issue is very similar to that of music (which I discuss here):

- Neither taṣwīr nor music are mentioned in the Quran.

- Neither are clearly and unequivocally prohibited by a command of the Prophet PBUH.

- There is no good logical reason for prohibiting either; both have good and wholesome uses that do not cause any difficulty to the conscience or repugnance to one’s sensibilities.

- Both of them are associated with highly sinful activities; taṣwīr with the worship of idols, music with maʾāzif (wild parties involving wine-drinking and half-dressed women), so that a Traditionalist wishing to be safe from sin would have a strong incentive to stay away from both regardless of any expected benefits.

- The majority of the world’s Muslims refuse to take either prohibition seriously.

On the unreliability of the hadith narrations mentioning 73 Muslim sects, 72 of which are supposedly doomed to the Hellfire

There are a group of hadith narrations, not found in al-Bukhārī and Muslim, but found in various other collections, in which the Prophet Muhammad PBUH mentions that the Muslims will divide into 73 groups, 72 of which will enter the Hellfire, meaning that only one among these 73 groups will be saved. This one group is known as al-firqa al-nājiya (“the group that attains salvation”).

These narrations have unfortunately been a favorite polemical tool. Each group can claim to be al-firqa al-nājiya to imply that the members of every other group will enter the Hellfire:

But they tore themselves into sects; each party (self-righteously) happy with what they have.1

The truth of the matter is that these narrations are all likely corrupted or fabricated, and there is no authentic evidence whatsoever for the part that says “all of them will enter the Hellfire except one”.

The Kuwaiti Islamic scholar Dr. Ḥākim al-Muṭayrī (b. 1964, holds PhDs in Islamic studies from Birmingham University and University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, Morocco) has conducted a study (Arabic PDF – 3 MB) of all of the relevant hadith narrations regarding this issue. He mentions that Ibn Ḥazm rejected the narration, and that al-Shawkani considered the part that says “all of them are doomed save one” a fabrication. In the conclusion, he writes:

وعلى كل فكل طرق هذا الحديث مناكير وغرائب ضعيفة ومنكرة، وأحسنها حالا حديث أبي هريرة وهو حديث حسن، مع تساهل كبير في تحسينه لتفرد محمد بن عمرو به، وهو صدوق له أوهام خاصة في روايته عن أبي سلمة عن أبي هريرة، ولهذا كان القدماء يتقون حديثه كما قال يحيى بن معين.

All of the ṭuruq (the chains of narrators) of this hadith are objectionable and unauthentic. The best of them is the hadith of Abū Hurayra, which is a ḥasan hadith (i.e. not good enough to be considered authentic, but having an acceptable meaning and not clearly fabricated), provided that we extend it great latitude (i.e. lower our standards) for the fact of Muhammad bin ʿAmr being its only transmitter, who is known to be a truthful person who has awhām (plural of wahm, "confusion" or "delusion", meaning he gets confused and mixes up narrations), especially in his narrations from Abū Salama, from Abū Hurayra, and for this reason the early hadith scholars were cautious of his narrations, as Yaḥyā bin Maʿīn has mentioned.

Note that this best hadith that Dr. Muṭayrī refers to does not have the part that says “all of them will enter the Hellfire save one” (see page 24 of the PDF). The most we can learn from these narrations is that the Muslims will possibly divide into 73 sects (which could possibly be a randomly chosen number used to imply “a great many”, as is typical in Arabian usage).

In conclusion, there is no justification whatsoever for using these narrations to imply that Muslims from other groups will enter the Hellfire; anyone who says such a thing has uttered a falsehood, either out ignorance or dishonesty.

The Muslim World on the Eve of Europe’s Expansion by John J. Saunders

The Muslim World on the Eve of Europe’s Expansion (published in 1966), at only 136 pages, is a short and enjoyable history of the Muslim world in the early modern period, with interesting articles on the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal Empires, the Mamlukes, the Uzbeks, Islam in Southeast Asia and Africa, the remnants of the Mongols in Russia, the Indian Ocean trade and the naval struggle between the Ottomans and the Christian powers.

Many interesting scenes from history are presented in the book; the siege of Vienna by the Ottomans; celebrations in Rome on the fall of Granada, the last Muslim principality in Spain; an Italian traveler who performs the Hajj in 1503 disguised as a Muslim.

The book is a collection of excerpts from other works. Each section is introduced by the fair-minded and able British historian John J. Saunders. The book is recommended to anyone who wants to enjoy a lighthearted and non-politicized introduction to the state of the Islamic world during the rise of European power.

On unanswered prayers, and is it normal for a Muslim to doubt God’s existence?

On giving up a sinful relationship

A Muslim who cannot escape the guilt of a sinful life

Why is seeking knowledge important in Islam?

Is it forbidden for a Muslim to fall in love with a Christian?

On sharing a room with a homosexual person of one’s own sex

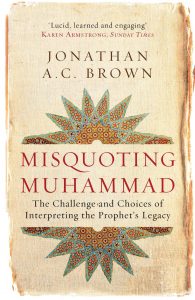

Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet’s Legacy [Short Book Review]

Professor Jonathan Brown’s Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet’s Legacy is one of the best English-language books about Islam written by a Muslim (he converted to Islam in 1997). While the book’s focus is on the issues surrounding the authenticity and interpretation of hadith, it provides a good general history of the development of Islam’s intellectual tradition.

The book will contain many eye-openers for Muslims and non-Muslims alike. While rising many questions, the book does not generally provide conclusive answers.

The issue of violence against women (as in verse 4:34) is covered in great detail, although no solution is reached (see my essay A New Interpretation of Wife-Beating in Verse 4:34 of the Quran for a potential solution). On the issue of the stoning of adulterers:

...and so strong was the sense of duty to avoid carrying them out that Cairo’s senior judge chose exile over agreeing to execute two adulterers.

While the Egyptian scholar Muhammad Abu Zahra is mentioned in the book, his important opposition to the punishment of stoning is not (perhaps Dr. Brown was not aware of it).

This book’s most important contribution, I hope, will be to encourage other Muslims to write works of similar quality; fairly balanced and supported by a great deal of evidence.

On responding to criticisms of Islam and the Prophet Muhammad

On praying (making dua) during salah and whether one can do it in English

Balancing materialism and fatalism

Wanting to get married as a Muslim woman but having no suitors

Solution for a person who due to illness cannot make up missed fasts

A new approach to the Quran’s “Wife-Beating Verse” (al-Nisa 4:34)

In der Moschee by Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner (d. 1894)

In this essay, I present a plausible framework in which traditional scholarly interpretations of 4:34 can be considered correct without this becoming support for violence against women. I argue that the error has not been in understanding 4:34 but in scholarly efforts to justify it. There is a new line of justification that has so far been largely ignored and not taken to its conclusion. Verse 4:34 places a duty on men, rather than granting them a privilege, to be enforcers of social order–a heavy task that most men are not meant to enjoy.

Among middle class Muslims wife-beating is highly taboo. Muslim men do not need to look at religious references to decide whether they should approve of wife-beating or not; they justify a highly discriminatory attitude against wife-beaters in cultural and ethical—rather than legalistic—terms. A man who thinks it is acceptable to beat women is so crude, vulgar and uncivilized that he is considered unworthy of befriending or even speaking to. He is excluded from social circles and sympathy is extended to any women unfortunate enough to be associated with him. Yet these men who consider wife-beating completely unacceptable are devout Muslim men who believe in the letter of the Quran, including verse 4:34, which appears to encourage wife-beating.

This leads to a sociological conundrum that is often naively solved by asserting that these men are abandoning parts of Islam in order to be more humane and civilized. As I will argue in this chapter, a sociologically sophisticated analysis shows that it is quite possible to accept and adopt the plain sense of verse 4:34 while remaining humane, civilized and completely opposed to domestic violence.

Islam is often called a misogynistic religion. But if one checks out traditional works of Quranic exegesis, one finds a striking phenomenon: almost every scholar who has tried to interpret verse 4:34, in which a man is given the right to strike his wife in certain circumstances, has been at pains to place restrictions on it, as Karen Bauer discovered in her study of the historical Islamic sources on this issue.1 There were no feminists in the 8th century pressuring these scholars to be politically correct. We are talking about a time when the Viking campaigns of rape and plunder against the rest of the world were just starting to take off (and would continue for the next three centuries). What was making these men of those “Dark Ages” so sensitive toward women’s rights? I would argue that it was because they were humans taught by Islam to see women as fellow humans, and a chief feature of the human psyche is empathy when this empathy is not blocked due to the dehumanization of others. They had mothers, sisters, daughters and wives and did not like the thought of these loved humans suffering oppression and injustice.

Be that as it may, an uninformed reader who picks up an ancient Islamic text expecting to read things like “beat your wives, they are your property anyway” will be highly disappointed to find the depths and nuances of the Islamic discussions of the issue. Those who study Islam closely, the most important group being Western, non-Muslim scholars of Islam, are forced, often against their expectations, to respect it more the more they learn about it.

Like the scholars of ancient times, and like Prophet Muhammad PBUH himself (as will be seen), many Muslims feel uncomfortable with verse 4:34 of the Quran. It is difficult to find a balanced and holistic interpretation that does not either defend wife-beating or that does not nullify the verse completely. This essay attempts to provide such an answer; taking the traditional meaning of the verse seriously while explaining how it fits within a modern society in which violence against women is rare and taboo (as it should be). To begin addressing the issue, the first principle we can state on this matter is this:

There is no such thing as humanely striking a woman.

Contemporary Islamic scholars who wish to defend 4:34, such as Yusuf al-Qaradawi, often mention that there are various restrictions in Islamic law on the way a man can strike a woman, as if this somehow justifies it. It does not. What needs to be answered is why the Quran allows any form of striking at all.

Let’s now take a look at verse 4:34:

Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, as God has given some of them an advantage over others, and because they spend out of their wealth. The good women are obedient, guarding what God would have them guard. As for those from whom you fear disloyalty, admonish them, and abandon them in their beds, then strike them. But if they obey you, seek no way against them. God is Sublime, Great.2

The Arabic word qawwāmūn is translated as “protectors and maintainers” in English or something similar to it, and this leads to the verse sounding nonsensical. Why would the Quran go from the idea of financial support and protection for women to the idea of striking them in the same verse? The problem is that “protector and maintainer” is not exactly what qawwāmūn means. Qawwāmūn means “figures of authority who are in charge of and take care of (something)”.3 Verse 4:34 is about the issue of authority and law-enforcement within a household as I will explain, the idea of financial support and physical protection is only a subset of it.

Verse 4:34 establishes qiwāma, the gender framework within which Muslim families are meant to operate. The concept of qiwāma, along with that of wilāya (guardianship), have been a focus of concentrated feminist efforts that aim to defuse them in order to create gender equality within Islam.4 In a chapter of Men in Charge? Omaima Abou-Bakr tries to trace the way the concept of qiwāma developed in Islam. She mentions Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī by the Persian scholar Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310 AH / 923 CE) as the “first” work of tafsīr (Quranic exegesis), going on to say:

Hence, not only did al-Tabari initiate and put into motion the hierarchal idea of moral superiority and the right to discipline (ta’dibihinna), but he also instituted the twisted logic of turning the divine assignment to provide economic support into a reason for privilege: ‘they provide because they are better, or they are better because they provide’.

The truth is that the pro-qiwāma interpretation of verse 4:34 starts not with al-Ṭabarī. It started as early as the Islamic scholar and Companion of the Prophet Muhammad PBUH ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbbās [ra], in whose work of tafsīr5, authored two centuries before al-Ṭabarī, he says:

"Men are qawwāmūn over women" means umarāʾ ("commanders", "rulers", "chiefs"), she is required to obey him in that which he commands her. His obedience means that she should be well-mannered toward his household, she should watch over his property and [appreciate] the virtue of his taking care of her and striving for her sake.6

Incidentally, among other works of tafsīr predating al-Ṭabarī, also by two centuries, are the works of Mujāhid and al-Ḍaḥḥāk. Another early work of tafsīr is that of Muqātil bin Sulaymān (d. 150 AH / 767-768 CE), who predates al-Ṭabarī by a century and a half. Muqātil interprets qawwāmūn as musalliṭūn (“having lordship and authority”), a word that is largely similar to Ibn ʿAbbās’s umarāʾ, from the word sulṭa (“authority”, “dominion”).7 Al-Ṭabarī’s understanding of qawwāmūn was not new; he was following a tafsīr tradition that had been established centuries before him. The pre-Ṭabarī Ibāḍī scholar Hūd bin Muḥakkam al-Hawwārī (died in the last decades of the third century AH), reflecting a North African tafsīr tradition, also interprets qawwāmūn as musalliṭūn.8

Abou-Bakr goes on to conclude that al-Ṭabarī was responsible for the changes she mentions in the following passage:

Thus, the original direct meaning of qawwamun/bima faddala (financial support by the means God gave them) developed this way: 1) from descriptive to normative/from responsibility to authority; 2) introducing the noun qiyam (which paved the way to the later qiwamah) as an essentialist notion of moral superiority; 3) from the restricted meaning of providing financial support to a wider range of a generalized status of all men everywhere and at all times; and 4) from a relative, changing condition of material bounty on account of inheritance to an unconditional favouritism based on gender.

According to Abou-Bakr, an innocent and harmless verse 4:34 was over time given a patriarchal, male-centric interpretation by scholars like al-Ṭabarī. Such a narrative, if it were true, would certainly be strong support for the feminist cause. But Ibn ʿAbbās and Muqātil’s aforementioned interpretations are strong historical evidence against her thesis; the notion of qiwāma did not go from being merely about financial support among the early Muslims to something more later on through the harmful influence of tafsīr scholars; qiwāma was thought to be about authority from the time of the Companions. A second and equally serious flaw in her thesis is her considering financial support to be central to the verse’s reasoning. Verse 4:34 actually mentions financial support as the second, rather than the first, rationale for giving men authority over women (I will later discuss what this authority means, whether it can ever be fair and just, and the limitations Islam places on it). Let’s take another look at the relevant part of the verse:

Men are qawwāmūn over women as God has given some of them [i.e. males] faḍl [a preference, advantage, superiority in rank] over others [i.e. females], and because they spend out of their wealth.

The first reason for this authority is not men’s financial support of women, but a faḍl (“preference”) that God has given to men over women, as is recognized by Muqātil9. To clarify further, the verse can be rephrased as:

Men are qawwāmūn over women because 1. God has given men a faḍl over women, and 2. because men spend out of their wealth.

The superiority in rank, status or nature supposedly granted to men by God is what comes first, it is the main justification for qiwāma and has nothing to do with financial support as far as one can tell, since financial support is mentioned separately. As I will discuss below, this does not mean that men are morally superior to women, we can use the Quran to argue for the opposite. But to continue the discussion of rank, the Arabic wording of the verse can be said to go out of its way to make the separation between men’s rank and men’s financial support of women clear by using two bi-mās (“because”s) rather than one: because … and because … . It is quite unwarranted to collapse these two given reasons into one and claim that the verse is merely giving men the duty of supporting women’s welfare.

There are many hadith narrations that mention women as deficient in intellect and morality. I make no references whatsoever to those narrations in this discussion; the “preference” I refer to is the plain meaning of the Quranic verse; it is a rank granted by God, the way an army grants different ranks to different soldiers without suggesting that the lower ranks are morally inferior to the upper ranks. The concept of men having a superiority in rank over women is not unique to 4:34, it is also spelled out in verse 2:228:

Divorced women shall wait by themselves for three periods. And it is not lawful for them to conceal what God has created in their wombs, if they believe in God and the Last Day. Meanwhile, their husbands have the better right to take them back, if they desire reconciliation. And women have rights similar to their obligations, according to what is fair. But men have a degree over them. God is Mighty and Wise.

Scholars, such as al-Wāḥidī, Ibn al-ʿArabī, al-Rāzī, Ibn al-Jawzī, Abu Ḥayyān al-Gharnāṭī and Ibn al-Qayyim, mention that women are intrinsically mentally and morally inferior to men in their justification for the Quran’s special treatment of them in the matter of testimony (a man’s testimony equals two women’s, with various differences and nuances among the schools).10 A strong argument against the mental/moral inferiority thesis is that the Quran treats women as men’s equals throughout, considering them equally responsible for their actions and holding them to the same standards. If women were as irresponsible and foolish as children as some scholars suggest (such as al-Wāḥidī, Ibn al-Jawzī and al-Rāzī, who mention that women are perma-adolescents, never maturing), it would have been only fair to treat them as children in the matter of duties and punishments, yet the Quran treats them as complete humans. Karen Bauer writes:

But if women were deficient in rationality, then why did they have spiritual responsibilities similar to men? Although the majority of exegetes simply took inequality for granted, several explained why such inequality was fair, just, and according to God’s will. Such interpretations may reveal more, however, about the worldview of the interpreters than they reveal about the Qurʾān.11

A modern work of tafsīr that criticizes the infantilization of women in classical tafsīr works is Tafsīr al-Manār by the Egyptian reformist scholars Muhammad Abduh (d. 1905 CE) and Rashid Rida (d. 1935 CE).12

Before we go on, we can summarize the evidence in support of the classical view of qiwāma as:

- Classical scholarly works, such as those of Muqātil, al-Ṭabarī and al-Rāzī.

- The opinion of the Prophet’s Companion Ibn ʿAbbās.

- The wording of the verse, in which the primary rationale for qiwāma is given as a superiority in rank granted by God, rather than financial support.

- The fact that the verse seems to absurdly switch from the issue of financial support to the issue of discipline if we accept the feminist interpretation that qiwāma has to do with financial support alone. But if we accept the classical view that it is about authority, then the verse makes perfect sense: The first part asserts that men are the chief authorities in their households; the middle part gives two reasons for this; the last part deals with the issue of what a man should do when this authority is challenged.

Laleh Bakhtiar’s interpretation of “and strike them” as “leave them” in her Sublime Quran is so far-fetched that it is not worth addressing. Men in Charge? does not give it a mention and assumes that “strike them/beat them” is the correct interpretation. Despite the book’s attacks on traditional qiwāma, the question of why the verse mentions striking women at all is strangely not addressed in the book as far as I could find. It is quite far-fetched to claim that a verse that allows the male to strike the female is innocent of patriarchal concepts.

Another line of attack against qiwāma has been that of claiming that Quranic verses and principles are historically localized; they applied in the Arabia of the 7th century CE, but they do not necessarily apply today. Addressing this criticism would require another essay. The belief that Quranic principles are historically localized is debatable, it is against the understanding of the vast majority of Islamic thinkers and scholars. We can localize a verse in its historical context to understand its meaning and intent, but once we have extracted these, they should be generalized to all times and places. Historical localization would allow one to nullify almost any Quranic concept they want by arguing that it only applies to a particular time and place and not to another. The common and common-sense understanding of the Quran is that while its context can help us extract its meaning, the meaning itself is universal. The default assumption regarding the meaning of any verse should be that it is designed to be applied by all humans for all time. Overwhelming evidence should be needed to prove that the meaning of a particular verse has expired or is irrelevant today. In the case of qiwāma, there is no evidence at all that it is irrelevant today. There certainly is overwhelming desire among a certain group of intellectuals to throw the concept away, but that does not constitute evidence. Working for women’s rights is a good thing, but destroying the foundations of our understanding of the Quran in the process is not.

If the Quran was written by the Prophet PBUH, then it would make sense that its meanings would expire and would be limited to the narrow context of 7th century Arabia. He was only a human and could not foresee all eventualities. But we believe the Quran is from God, it is His unchanged Words, which means that we have to treat it like a book written by an infinitely wise person who could foresee the fact that humanity would continue for the next 100,000 years (or however long). If something was supposed to only apply to one circumstance and not to others, then God would have told us so. What we believe is that the Quran was written by the Creator to be applied for all time. Saying that God was so short-sighted that He gave a universal command in His book that does not apply any longer is a great insult against the Creator of the universe. The question then becomes about the nature of God: mainstream Muslims believe that the Quran is from the same Creator who designed the laws of quantum mechanics and who watched the universe age for billions of years before humans started to walk the earth. When such a God tells us men should have a rank above their wives in their households, He is not stuck in the mindset of 7th century Arabia but is speaking from a billion-year perspective. Those who argue for historical localization are saying the opposite; they are saying that God was not intelligent and wise enough to see beyond 7th century Arabia. Therefore a person who argues for historical localization should first prove to us that God is not as intelligent and wise as we tend to think.

At this point, assuming that the classical interpretations of the verse are correct, we will examine how such a gender framework could be justified among civilized and self-respecting humans.

Domestic Violence in Islam

Domestic violence, as the phrase is commonly understood, is prohibited in Islam; a woman has the right to not be abused by her husband. This is the general rule; Islam does not tolerate cruelty and injustice toward anyone, whether man, woman, child or even animal. But verse 4:34 establishes an exception in the matter of authority and discipline in a household. The point of this verse is the establishment of a certain type of order within an Islamic household.

To explain how 4:34 can be implemented without this leading to domestic violence, the best analogy and the most relevant I have found is that of law enforcement. Throughout the world, the police have the right to strike a person who is about to break the law, for example a person who wants to set fire to a building. The police are required to sternly warn the person to stop their behavior, and if they do not, they have the right to intervene physically and subdue the person to prevent them from doing harm. The right of the police to strike any citizen they want given the appropriate circumstances establishes a certain type of order within society. It does not lead to a reign of terror; look at a peaceful and quiet Western town and you will find that that peace and quiet is protected by the existence of a police force that has the right to use violence when necessary.

In the West, law enforcement is the job of the police; they are given the right to use violence when necessary to carry out this job. Islam creates a second law enforcement jurisdiction that is non-existent in the West, that of the family, with the power of policing given to a husband (rather than a police force) within this internal family jurisdiction (later on I will discuss possible reasons for why this power is given to men rather than women).

Similar to the police, men are not allowed to abuse this authority. Police brutality and husband brutality can both be severely punished by the law. Verse 4:34 gives a man the authority to police his household. If his wife is about to do something highly damaging, such as trying to invite a lover into the house, he has the right to sternly warn her to stop and to use force against her if she does not.

Here, it should be stated that under Islamic law a woman should have the right to divorce any time she wants. If her husband is abusive, besides having access to agencies protecting women, she should also be able to threaten to leave him, and the police should be there to protect her rights and prevent her from being kept as a wife against her wishes. Middle Eastern countries have been notoriously bad at protecting women’s rights, this is slowly changing, and Islam can actually be used as justification for creating agencies that protect women’s rights.

Islamic law creates this situation inside a family:

- A husband has the right to police his household and to use violence in the extremely rare case where his wife wants to do something completely unacceptable in their culture and society.

- A woman has the right to leave her husband any time she wants.13

- A woman has the right to be free from cruel treatment and abuse, and has the right to enjoy the police’s protection from abuse.

In the vast majority of marriages (perhaps 99.99%), husbands will never have to use their right to violence, the same way that in a peaceful society the vast majority of people are never beaten by the police, despite the fact that the police have the right to strike any citizen when necessary. Islamic law, similar to Western law, creates a certain social order that does not do violence to anyone as long as no one tries to break the law. A husband’s right to act as policeman is irrelevant except in the extremely rare case when a wife, for whatever reason, 1. insults and threatens him by her actions, 2. does not listen to admonishment and 3. does not want a divorce. That is quite a ridiculous situation that very few couples will find themselves in.

A person may ask, if this verse truly applies to only 0.01% of marriages, why would the Quran have a verse about it? For the same reason that Western law has many clauses on the use of violence by the police despite the fact that only 0.01% of citizens are ever subject to police violence. The right to use violence is what matters here, not the actual use of violence. When a Western town gives the police the right to use violence, they do not do so because they like to watch the police beat people, but because they know that if the police did not have the right to use violence, they could not deal with the extremely rare cases in which violence is needed.

You cannot establish social order without giving someone the power to enforce it. A law is useless unless there is someone who can enforce it, and the enforcement of law in human society requires the power to use violence (only the power, not the actual use of violence). While Western law defines a certain legal code enforced by the police where necessary, Islamic law defines such a code, and in addition to it, defines internal family law (non-existent in the West) that husbands can enforce through violence where necessary.

Senseless Beatings and Cultural Mores

When talking about 4:34, people’s minds often jump to an imaginary or real wife who is beaten by a cruel husband. But that has nothing to do with 4:34. The violence in 4:34 is similar to police violence; if it is cruel, if it is senseless, if it is unnecessary, then that is forbidden and should be punished by law. 4:34 only justifies violence in cases where the couple’s culture considers the violence justified. The woman’s own relatives should be able to look into the case and agree that the husband’s actions were justified.

What situations could possibly justify a husband striking a wife? This is similar to asking what situations could possibly justify the police striking a citizen. If we think of good citizens being beaten by the police, we naturally find that cruel and unjustified. So to correctly answer the question, we have to think of bad citizens, those who do deserve violence according to the law worldwide. A bad citizen would be one who is mugging someone, or trying to steal a car, or trying to rape a woman. People will generally agree that police violence is justified in preventing such citizens from carrying out their intentions.

Verse 4:34 deals with the issue of bad wives, the way that Western laws allowing police violence are there to deal with the issue of bad citizens (I will address the question of bad husbands later on). In regards to good wives versus bad wives, verse 4:34 has this to say:

The good women are obedient, guarding what God would have them guard. As for those from whom you fear disloyalty, admonish them, and abandon them in their beds, then strike them.

The Arabic word that is rendered as “disloyalty” above is nushūz, which according to al-Rāzī has a meaning close to “mutiny”, it is when a person acts as if they are superior to a figure of authority (as in a soldier acting in disregard of an officer’s rank).14 It literally means “to consider oneself superior”, the word can be used to describe a patch of land as being higher than another.1516 Interestingly, it is also used in the Quran in reference to a man’s misbehavior toward his wife, which provides an illustration of the fact that a husband is not an absolute authority; he too can be mutinous against the higher authority of the law if he is abusive or negligent toward his wife.17

The word nushūz is vague and does not clearly define what situations deserve a strong response and which ones do not. I believe this is in order to leave it to each family, culture and society to decide it for itself. All wives probably know what their husbands’ “deal-breakers” are, things that he would consider a severe insult and a betrayal, and these things can be different for different people. The most flagrant case of nushūz is a wife trying to have an affair. In general, nushūz is any case in which a wife acts in disregard and disrespect to the Islamic social order that the Quran wants to establish within the family. Among forms of nushūz explained in the Islamic legal literature are, many of which sound antique or somewhat irrelevant today:

- A woman refusing to engage in sexual intimacy with her husband without a valid reason.18 Ibn Rushd al-Jadd (grandfather of the more famous Ibn Rushd), in answer to a question, says that a man is not allowed to strike his wife if she refuses sexual intimacy unless she is doing it out of malice and spite and he fears she will continue to become more rebellious.19

- Refusing to do housework. The Ḥanabalī scholar Ibn Qayyim al-Jawzīya (d. 751 AH / 1350 CE) considers it a duty, saying that the marriage contract assumes that the woman perform such services,20 while the Shāfiʿī jurist Abū Isḥāq al-Shīrazī (d. 476 AH / c. 1083 CE) does not consider housework one of her duties.21 According to the Spanish Malikī scholar al-Qurṭubī (d. 671 AH / c. 1273 CE), whether housework is obligatory depends on her social class; it is not obligatory for upper class women who expect their husbands to hire servants.22

- Refusing to join the man in his home after marriage without a valid reason.

- Inviting someone into her marital home against her husband’s wishes.

A technical, modern and pluralistic definition of nushūz would be:

A woman's acting in flagrant disregard of the terms implied by her marriage contract in her particular culture.

Is it acceptable for a husband to use violence against his wife for refusing him sexual intimacy, even if she is doing it maliciously, for example as a form of emotional blackmail? Most, if not all, people today will probably say violence is not justified; they should work out their issue peacefully or get a divorce. And that is the correct general principle today. What constitutes scandalous behavior that deserves a decisive response from a husband can change as humanity develops.

The Quran does not give us a strict definition of nushūz, allowing us to make its scope wider or narrower as our reason, conscience and cultural experience demands. Any case of a woman suffering violence in a way that is clearly unjust and unreasonable can automatically be considered outside the bounds of 4:34: In a Muslim society, a woman should never have occasion to say that her husband beat her without a valid reason. If that is true, her husband should be punishable by law, as is the opinion of Ibn Ḥazm.23 Scholars, however, have historically differed greatly on whether and when a man can be held accountable for striking his wife, some going as far as practically prohibiting all violence and others giving a man carte blanche to beat his wife whenever he wants.24 But thanks to the vagueness of the concept of nushūz, we are under no strict limitation in our ability to give it a reading that fits reason and conscience. In my proposed interpretation of 4:34, if a wife was struck by a husband, it would only be justified in situations like this:

I tried to cheat on my husband, he found out and sternly warned me to give up the idea. I did not. He told me I should get a divorce if I do not want to be with him anymore, but what I want is to stay married to him and enjoy the benefits that come with it while having a lover on the side. We had a fight and he physically subdued me and took my phone away from me so I would not be able to speak with my lover.

In a Western country a husband in the above situation is required to let his wife do whatever she wants, only having recourse to divorce. The police will probably laugh at him if he was to give them a call and complain that his wife wants to sleep with another man. Under Islamic law, however, a husband is given the authority to be the law-enforcer himself in such a case. This creates a situation in which there is zero tolerance for a wife acting against the terms of her marriage. She is required to either accept to live amicably and faithfully with her husband or to get a divorce. Verse 4:34 ensures that there will be no “in-between” situations where a wife is only half faithful or respectful toward a husband, for example staying with him for the sake of the children while doing whatever she wants in her private life without concern for his interests. She is either fully committed to her life with her husband or she gets a divorce. While Western law tolerates all shades of commitment from full commitment to zero commitment between a husband and wife, Islamic law allows only full commitment or divorce, and gives the husband the right of violence to ensure that this will be the state of things in his family.

Laws versus real-life

Above, I have explained the theory behind verse 4:34. But that is only half the picture. Verse 4:34 creates a certain social order, a certain type of society, that an outsider may be completely unable to imagine from the wording of the verse. The type of society it creates is one in which it is unthinkable for a woman to flagrantly act in opposition to her husband and his household (the most glaring example being that of infidelity). It is as unthinkable for her to act thus as it is for a Western citizen to think of counterfeiting money. While in the West we do not live under a police reign of terror, we know that if we were to do something that severely threatens social order, such as making counterfeit money, law-enforcement will have something to say about it. We do not need the police to strike us to not make counterfeit money. We just know that in our society, in our social order, the making of counterfeit money is totally unacceptable and will bring down violence on the person who tries it.

In the same way, in an Islamic society, a woman knows that within the social order she lives in, she cannot act flagrantly in opposition to her husband; she knows that this is totally unacceptable in her society and can bring down violence on her. If there is a need for her to oppose her husband, she has the right to argue with her husband, to demand the support of her family and his family, to demand the support of women’s agencies, to sue him in court and to threaten divorce. These things ensure that her husband cannot abuse his authority and that her rights are not neglected. What she does not have the right to is acting in a way that damages her husband and his household. She is free to get a divorce; but while she chooses to be with him, she has to act in good faith toward him.

The “Rule” of Husbands

Giving husbands the right of policing does not make them tyrannical rulers, the same way that giving the police the right of policing and striking citizens does not make them rulers in society. Husbands and the police are both subject to higher laws that restrict their powers. In an Islamic society, both the husband and wife are subject to the law and its various restrictions. They are both servants of God who are required to do their best to please Him. One of them, the husband, has the powers of the police delegated to him to deal with the extremely rare case of having to enforce internal family law. It is true that no sensible wife would act in a way that threatens her husband and his family, similar to the way that no sensible citizen would act in a way that threatens society and requires police action. But not all wives or citizens are sensible, therefore the law sees the need to give certain people the right to use violence against those rare wives or citizens that do not act sensibly.

In focusing on the extremely rare situations when violence becomes necessary, discussions of Islam and domestic violence ignore the overwhelming majority of marriages in which a husband striking his wife is considered unthinkable. It is like focusing on police brutality in a peaceful town and ignoring the 99.999% of the citizenry who live in peace and never have any dealings with the police.

A husband who habitually beats his wife is similar to a policeman who habitually beats citizens for no reason. Such a husband or policeman should be severely punished, and if they cannot stop their violence, they should be fired from their jobs (a judge should force the husband and wife to separate, and should fire the policeman).

Why Make Husbands Policemen?

Even if it is admitted that the mere right of using violence against a wife does not lead to an epidemic of domestic violence (and my experience of Muslim societies in Iran, Iraq and the United States illustrates this beyond doubt), one may doubt if giving men the authority to act as part-time policemen in their households is the best way to organize society.

The Quran’s theory is that society functions best when husbands are recognized as authorities in their households, with the power to act swiftly, decisively and even violently when their interests are seriously threatened.

The feminist (etc.) theory is that society functions best when a husband and wife have equal shares of authority in their households, somewhat similar to a country or company having two presidents.

Which theory is true? A great many scientific studies would be needed to find out beyond reasonable doubt which type of society functions best. Such studies should try to answer these questions:

- Do women in devout Muslim households suffer more or less domestic violence compared to other women?

- Are women in devout Muslim households more or less likely to suffer depression than other women?

- Are women in devout Muslim households happier and more fulfilled or less compared to others?

- Are children brought up in a devout Muslim family more or less likely to suffer trauma compared to children brought up in a non-devout Muslim family, compared to children brought up in non-Muslim families from societies of equal development and prosperity?

- What type of society is more sustainable? Devout Muslim societies are sustainable in that families can produce enough children to replace the parents. Western societies are all failing at this; they are all slowly going extinct.

Note the keyword devout. Considering an alcoholic who regularly beats his wife representative of Islam just because he calls himself Muslim is something only a propagandist would do. Any study of the effects of the Quran’s teachings, including the teaching in verse 4:34, should focus on people who actually take the Quran’s teachings seriously.

My contention, and the Quran’s, is that a devout Muslim society will function better and will be happier than either a non-devout one or a modern, liberal and irreligious one.

Verse 4:34 explains why God considers men worthy of the authority He has given them in their households:

Men are qawwamūn (keepers, protectors and authorities) over women, as God has given some of them an advantage over others, and because they spend out of their wealth. The good women are obedient, guarding what God would have them guard. As for those from whom you fear disloyalty, admonish them, and abandon them in their beds, then strike them. But if they obey you, seek no way against them. God is Sublime, Great.25

The Quran gives two reasons:

- Men are inherently (i.e. genetically) suited to the role of being figures of authority in their households

- Men are the financial maintainers of women (by Islamic law)

The Quran’s contention, therefore, is that a family functions best when a man is the chief authority, because it is in the nature of human families that they function best when a man is the chief authority. We have no convincing scientific evidence for this at the moment, but we may have it in ten or twenty years. According to the Quran, humans have evolved (for a plausible reconciliation of Islam and evolution see my essay: God, Evolution and Abiogenesis) in a way that makes males different from females, and this difference justifies different roles within a relationship.

This difference does not mean that a man is given the right to do whatever he wants in his family. He is subject to the law and any abuse of his powers can be punished by law.

The question of whether men are really evolutionarily suited to be the chief authorities in their families cannot be settled by argument. It requires hundreds of scientific studies. Simply thinking of the 1% of men who abuse their powers tells us nothing about the 99% who do not. You cannot judge social policy by thinking of a few glaring bad examples. You have to study all of society. You cannot judge verse 4:34 by thinking of the hundred families in a Muslim city in which the husbands are abusive and ignore the 10,000 families in which the husbands are not abusive.

Bad Husbands

The passage 4:128-130 of the Quran deals with the issue of bad husbands, and refers to them as mutinous as already mentioned:

If a woman fears mutiny or desertion from her husband, there is no fault in them if they reconcile their differences, for reconciliation is best. Souls are prone to avarice; yet if you do what is good, and practice piety—God is Cognizant of what you do.

You will not be able to treat women with equal fairness, no matter how much you desire it. But do not be so biased as to leave another suspended. If you make amends, and act righteously—God is Forgiving and Merciful.

And if they separate, God will enrich each from His abundance. God is Bounteous and Wise.

Verse 4:35 is also relevant:

If you fear a breach between the two, appoint an arbiter from his family and an arbiter from her family. If they wish to reconcile, God will bring them together. God is Knowledgeable, Expert.

The above verses are taken to mean that in the case of bad husbands, a wife should either have recourse to their families, or to government-appointed judges, who have the right to try to reconcile their differences or to enforce a divorce according to the wife’s wishes.

Wives, unlike husbands, are not law enforcers in their households. Due to the genetic differences between the sexes, it makes no sense to ask a wife to use violence against her husband when necessary; men are physically stronger than women in the overwhelming majority of cases and could do dangerous physical harm to a woman. Therefore the woman instead has recourse to a higher authority than her husband when her husband is mutinous. That higher authority is her family, his family, government-appointed judges, and women’s agencies if any are available.

A modern, civilized society will ensure that women always have easy access to this higher authority that can swiftly deal with bad husbands when necessary.

Devout Muslims and Habitual Wife-beaters

It is my contention that the more devoutly Muslim a man is, the less likely he is to be a wife-beater. There are hundreds of verses in the Quran that call him to be kind and forgiving. A single verse that allows violence in extremely rare circumstances is not going to be sufficient to wipe out the teachings of these hundreds of other verses from his mind. Any person with sufficient intelligence to understand the Quran will feel restricted by it in his ability to be mean and violent toward others, including his own wife and children, rather than feeling encouraged by it.

I have no respect for a man who beats his wife and will never befriend a man who thinks he has the God-given right to beat women when the mood strikes him. I am not unique in this regard. In the devout Muslim society I come from, a man who is known to beat his wife is considered a low-life, a person unworthy of befriending. Yet we are all Muslims who take the Quran seriously, including verse 4:34.

Verse 4:34’s main function is a defense of Islam’s “patriarchy”. It makes it impossible to give the Quran a feminist reading that sees men and women as exactly equal. It gives men higher authority in their households and goes as far as delegating some of the powers of the police to them. This is a completely anti-feminist way of organizing society, and for this reason feminists who wish to “feminize” the Quran will be forced to either ignore 4:34 or to give it far-fetched interpretations (as Laleh Bakhtiar has done).

Those who have occasion to speak of 4:34 are generally middle and upper middle class people for whom domestic violence is unthinkable (and it is that way for me too). But saying that 4:34 is unnecessary because our men and women are mature and sensible enough to act as honorable adults toward one another is like saying the police are unnecessary because we sensible people do not plan to break the law.

The police’s main function is not violence; it is the protection of social order. By using violence against the very small minority of citizens who wish to break the law, a certain type of order is created that everyone follows. The same applies to verse 4:34. By giving husbands the right of violence against the extremely small minority of wives who desire infidelity and other ways of damaging their families, a certain type of social order is created where wives and husbands are required to be 100% committed to their families. 4:34 establishes a social order in which wives are either fully committed or get divorces. 4:35 and 4:128-130 establish a social order in which husbands are either fully committed are get corrected or punished by higher authorities.

The vast majority of wives are already fully committed and do not need violence to make them so, the same way that the vast majority of citizens are fully committed to being good citizens and do not need violence to make them so. But it is foolishness to say that social order does not need a policing power to protect it. Without a violent power protecting against threats to order, social order will break down, as seen in cases where the police abandon a town (such as during a police strike), which quickly leads to looting and rioting by irresponsible citizens.

The Islamic social order that requires wives to be fully committed functions peacefully and without violence in the overwhelming majority of cases; 4:34 ensures that there is a policing power that protects this social order and can respond to those extremely rare cases where this order is threatened.

People have the right to wonder if this is the best way to create happy families and societies. Without a great number of unbiased scientific studies there can be no conclusive answer. It might seem “obvious” to someone that this is not a good way to create happy families and societies, but this is just a personal bias unless they can provide statistical data to back up their opinion. There are faithful and loyal wives among both Muslims and irreligious people, but if devout Muslim wives are on average 50% more likely to be loyal, and their families are 20% more likely to be happy and to avoid being broken up, then that is all we need to know to tell us that we should not be too quick to judge the sociological consequences of the Quran’s teachings.