A Caravan with the Pyramids and Sphinx Beyond (Joseph Austin Benwell , 1868)

To many Muslims today, it will sound patently absurd if someone were to tell them that it is a mortal sin for them to draw a cat. But some religious scholars would tell you that drawing a cat is an act of taṣwīr (the depiction of living things in paintings, sculptures and elsewhere), a sin for which God supposedly promises the severest punishment.

Mainstream Sunni Muslims today follow the opinions of popular religious scholars like Muhammad al-Ghazali, Yusuf al-Qaradawi and Ali Gomaa, who by and large have no issue with drawings and statues. Since neither Muslims nor their respected scholars have an issue with taṣwīr, it is largely a theoretical issue within Islamic law. There is, however, a minority of puritan Muslims, especially on the internet, who often bring up this issue, claim that a severe and even violent distaste for taṣwīr is the proper Islamic stance, and who categorically reject the opinions of mainstream scholars like al-Ghazali, al-Qaradawi and Gomaa.

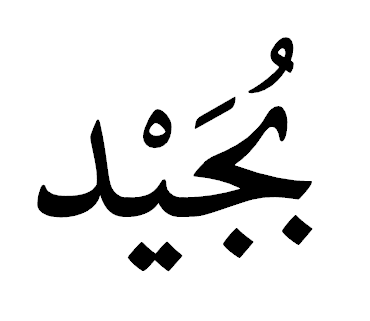

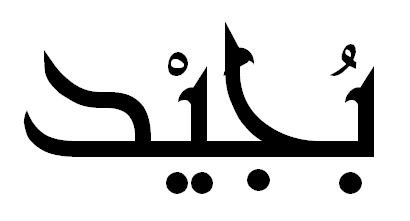

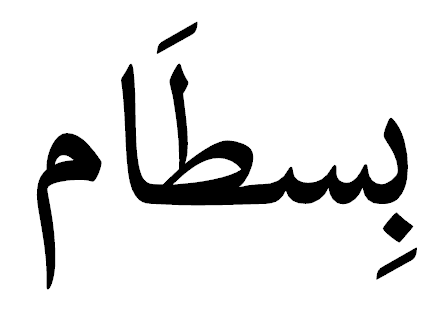

This article seeks to answer the needs of Traditionalist-minded Muslims on the matter of drawings and statues. Below I translate an Arabic article I discovered a few years ago by a well-informed Traditionalist author who criticizes the supposed prohibition on taṣwīr. This article is significant because when even such a Muslim can find good reasons to doubt the prohibition on taṣwīr, this acts as supporting evidence for the mainstream Islamic practice of tolerating it. The author is an anonymous user of the Traditionalist internet forum Multaqā Ahl al-Ḥadīth (The Meeting Place of the Traditionalists) who goes by the name of al-Shaykh Muḥammad ibn Amīn.

The author’s notes are in parentheses, while translator’s notes are in square brackets. I use the word “statue” to translate timthāl, a catch-all term for all statues, sculptures, effigies, murals and other three-dimensional figures depicting humans and animals. I use the word picture, painting, image and figure mostly interchangeably, choosing one over the other depending on the context.

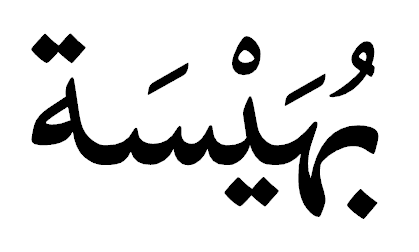

Beginning of Translated Article

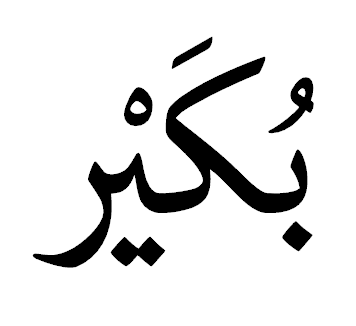

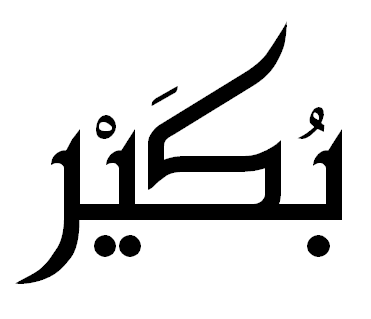

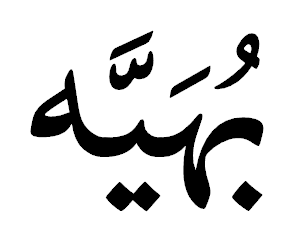

Ḥukm al-Ṣuwar wa-l-Tamāthīl – The Islamic Ruling Regarding Pictures and Statues

Praise be to God. There has long been a legal theoretic issue of dispute, in fact since the time of the Companions, and that issue is this: Do we enact the literal meaning of a text or do we enact its spirit? Meaning, do we apply the text in its literal and apparent sense, or do we try to understand its spirit and rationale? The Companions differed on this. You are probably aware of the hadith on the ʿaṣr prayer in the Banī Qurayẓa affair. Some of the Companion understood [the Prophet’s instructions PBUH] in their apparent form, while others tried to understand the purpose behind the instructions. The Prophet PBUH approved of the actions of both groups.

The issue [surrounding drawings and statues] is confused because there are texts mentioning instructions regarding the destruction of statues and the obliteration of pictures. Those who take these texts in their literal meaning would consider it obligatory to destroy every statue and obliterate every picture. Most of them [those who take the texts literally] consider photographic pictures permissible because they are merely the capturing of projections of light. And whoever prohibits this falls into contradiction since he is bringing together two mutually exclusive views.

The other opinion is that the reason for the prohibition of pictures and statues was to prevent them from becoming means of shirk [assigning divine powers to other than God] or tabarruk [considering an object a source of blessings]. Forbidding statues does not require that they should be worshiped. If they are regarded with veneration by people, then this is sufficient to prohibit them in order to prevent this veneration from developing into worship. For this reason many of the ulema [scholars] consider it permissible to place pictures in debased places. It is permissible [in their opinion] for a rug to have pictures on it since it is stepped on by people, preventing the pictures from being venerated. It is also permissible to create statues without heads, since this makes them appear deficient. And it is also permissible to place a picture in a place where it cannot be viewed. It is not permissible to place a picture (photographic or drawn) on a wall, but it is permissible to place it between the pages of a book if one can be sure that the picture is not venerated (for example if it is not the picture of a sheikh or wali). The majority permitted pictures of living things that do not have rūḥ [soul or spirit], such as plants and nature. There are even those who permitted the creation of statues and pictures if it was certain that they would not be venerated. Al-Qirāfī [a Mālikī legal theorist of the seventh century of the hijra] used to make statues himself, as he mentioned in his book Sharḥ al-Maḥṣūr.

Two types of statues are mentioned in the Book of God [the Quran]: The first type are those statues that are worshiped instead of God. These are called tamāthīl, aṣnām and anṣāb. It is obvious for us to say that these types of statues are prohibited for a Muslim to create or buy, since in such an act would be an aid in shirk. The second type are those statues that are not worshiped instead of God, such statues are not aṣnām or anṣāb. The Quran, in fact, mentions the creation of statues as one of the blessings that God bestowed upon Solomon [as]:

12. And for Solomon the wind—its outward journey was one month, and its return journey was one month. And We made a spring of tar flow for him. And there were sprites that worked under him, by the leave of his Lord. But whoever of them swerved from Our command, We make him taste of the punishment of the Inferno. 13. They made for him whatever he wished: sanctuaries, statues, bowls like pools, and heavy cauldrons. “O House of David, work with appreciation,” but a few of My servants are appreciative.

Here, God refers to statues as timthāl-s [statues] rather than aṣnām [idols], since they were not meant to be worshiped in God’s stead. This matter has to do with monotheism and faith and is a shared doctrine among all of the Prophets. There is no disagreement among the ulema that when it comes to the ʿaqāʾid [plural of ʿaqīda, beliefs regarding the nature of God and other matters] have not undergone change and that they have always been one and the same among the Prophets, for God says:

He prescribed for you the same religion He enjoined upon Noah, and what We inspired to you, and what We enjoined upon Abraham, and Moses, and Jesus: “You shall uphold the religion, and be not divided therein.” ...

Many authentic hadith narrations exist that insist that the muṣawwirīn [figure-makers] are in the Hellfire, and that they will be among those who suffer the severest punishment. The reason for their punishment according to the texts of the hadith narrations is that they imitate God’s creation, and muḍāhāt [the sin the texts accuse them of] is the same as mushākala [the creation of the likeness of something], meaning that they create sculptures in the likeness of God’s creation, so that on the Day of Judgment they are told: “Bring to life what you have created!” Al-Nawawī says in his Commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (14/84): “They [i.e. the ulema] agreed on prohibiting all [figures] that have shadows and on the necessity of changing them.” But Ibn Ḥajar adds in al-Fatḥ [his commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī] (10/388): “This consensus does not include children’s toys.”

There is conclusive evidence that the Prophet PBUH used pillows and utensils that had pictures on them, but he used to remove and wipe out pictures of crosses. It is also proven that he permitted children’s toys in the form of small statues/dolls, as is narrated from the Mother of the Believers Aisha, may God be pleased with her. Qaḍī ʿIyāḍ mentions that the majority of jurists permitted buying these dolls for the training of girls in matters pertaining to childcare, which is recognized as a worthy aim in Islamic law. While his information is correct regarding the permissibility of dolls, his reasoning is incorrect, since Aisha mentions a horse that had two wings; what relationship does that have with children’s education? The correct opinion is that children’s playthings are permissible for males and females without any karāha (legal disapproval), since they [dolls] are far away from the potential for veneration. One of our teachers used to say: “Children’s wisdom is greater than that of many adults, for you never find a child worshiping the doll he or she plays with.”

But if statues are an imitation of God’s creations, or creating their likeness, then that makes them forbidden and is considered a mortal sin according to the authentic narrations on the matter. But creating a likeness of God’s creations or imitating them could be done through making sculptures of soulless things like the sun, the moon, mountains and trees, and through making girls’ dolls and similar things that the texts explicitly permit. For this reason some of the ulema say that what is intended are those who create statues or make pictures with the aim of challenging God’s power, or those who think that they have a similar power to create as God has. God shows such people their incapacity by asking them to bring life to what they create. In support of this, Ibn Ḥajar, in al-Fatḥ al-Bārī [his aforementioned commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī], regarding God’s saying in His ḥadīth qudsī: “And who is greater in injustice than one who goes in order to create a creature like My creation?” interprets “goes” here to mean “aims”. According to this, the forbidden thing here is related to the intention of the maker [of the statue, etc.], whether the product is a statue or a hand-drawing of any image. It is mentioned in the Mawsūʿa al-Fiqhīya [The Encyclopedia of Islamic Jurisprudence, a 45-volume work by Kuwait’s Awqāf ministry including opinions from all of the four schools of Islamic jurisprudence, completed in 2005 after 40 years of work], in Bāb al-Taṣwīr [the chapter on figure-making]:

The majority of ulema agree that prohibiting figures does not imply a prohibition on possessing them or using them, for regarding the process of making figures of things that have souls, it is mentioned that figure-makers are cursed and that they will be punished in the Hellfire and that they will be among the most severely punished among the people, but nothing is mentioned regarding possessing pictures, and there is no accepted evidence for the existence of a reason for prohibiting the user of such figures. Despite that, there are narrations that prohibit the possession and use of pictures, but they do not mention a punishment or equivalent that imply that possessing figures is a mortal sin. For these reasons, the judgment regarding the possessor of pictures whose possession is forbidden is that they have committed a small sin... Among those who were aware of the difference between figure-making and the [mere] possession of figures were: al-Nawawī... and most of the jurists are in agreement with this.

As for narrations saying that the angels do not enter a house in which there is a figure or a dog, the likely intent are the angels of revelation and not others. For this reason Ibn Ḥibbān made this restricted to the Prophet PBUH, for the angels that are assigned to each individual would enter such houses, and God knows best.

The majority of the jurists have permitted the user of statues and pictures in houses if they are not placed on curtains or walls with the intent to view them with veneration, and if they are subject to debasement as in people stepping on them and so on. ʿIkrima says: “They used to dislike statues set up on pedestals, but they saw no issues with those which feet could step on.” ʿIkrima here is transmitting from [mentioning the opinion of] the Companions. Muḥammad ibn Sīrīn said: “They used to see figures that were spread out or stepped upon as different from those that were set up on pedestals.” Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr says in the Tamhīd (21/199): “This is the most balanced among the opinions and the most moderate in this matter and most of the ulema are in agreement with it. Whoever is fatigued with narrations [unclear meaning] will not oppose this interpretation. This is the best of what I believe about this matter. God is the helper toward the correct opinion.”

It appears that the permissibility of leaving alone figures and statues that are not venerated is the creed of the majority of the Companions, even their consensus. For they did not destroy statues and pictures in the countries of Persia, the Levant and Iraq, but they did so in India and the Arabian countries. That is because these things were not worshiped in Persia, the Levant and Egypt. They did not touch those enormous edifices and great numbers of statues which remain there to this day. Consider this anecdote:

Saʿd bin Abī Waqqāṣ (the conqueror of Iraq and one of those promised Paradise) [ra] entered the palace of Khosrow II in al-Madāʾin [Ctesiphon, the Persian capital, near modern-day Baghdad]. In that palace there were many figures on the walls and many statues. He did not destroy any of them, in fact they remain where they are to our day. None of the Companions criticized him or anyone else for this. This is a consensus from them regarding the permissibility of letting such things remain undestroyed if they are not worshiped in God’s stead and they are not ascribed holiness. Al-Tabarī says in his Tarīkh (2/464): “When Saʿd entered al-Madāʾin and saw its desertedness, and went to Khosrow’s hall, he went on to recite: “How many gardens and fountains did they leave behind? And plantations, and splendid buildings. And comforts they used to enjoy. So it was; and We passed it on to another people.” He performed ṣalāt al-fatḥ [ritual prayer performed after a conquest], which is not performed communally. He performed eight rakʿāt [units of prayer, plural of rakʿa] without pausing between them, and turned the hall into a masjid [mosque or prayer hall]. In it there were statues made of gypsum, of men and horses. Neither he nor the Muslims opposed their presence and left them where they were. It is said: Saʿd completed the prayer on the day he entered it, for he wanted to take residence in it [or take it as a seat of the new government]. The first Friday in which the Muslims gathered for Friday prayers in Iraq in al-Madāʾin was in the year 16 [of the hijra].” Also see the al-Dhahabi’s History of Islam (3/158).

In Khosrow’s hall there were colorful and life-sized pictures done in great detail. These pictures survive to our day. These pictures were, of course, not buried in the sand, rather, numerous companions entered this palace and stayed in it. How did they then not see the pictures which can be seen clearly to our day? Even if they were not able to destroy the pictures, they could have blotted them out through white-washing, and this does not require great expenses nor a large number of workers. It would have been easy for the ruling power to command that the walls be repainted. There is no other interpretation other than that they understood the hadith narrations regarding the destruction of figures as being specific to those which were accorded veneration or were worshiped in God’s stead. These pictures continued to be viewed, being described by historians and writers. Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī says in his Muʿjam al-Buldān [his famous geographical dictionary] (1/295): “In the hall there was Khosrow Anūshirvān picture, and that of Caesar king of Antioch, who was besieging it and fighting its people.”

The famous Abbasid poet al-Buḥturī describes them in his wonderful qaṣīda al-sīnīya [a type of ode]. He describes these pictures as having such detail that one could imagine them real, so that one would want to touch them to reassure themselves that they were mere pictures. He says in his ode:

Sorrows attend my saddle. I direct

my stout she-camel to Madāʾin [Ctesiphon].

When you see a panel of the Battle at Antioch,

you tremble among Byzantines and Persians.

The Fates stand still, while Anūshirvān

leads the ranks onward under the banner

In a deep green robe over yellow.

It appears dyed in saffron.

The eye depicts them very much alive:

they have between them speechless signs.

My wonder about them boils till

my hand explores them with a touch.

The question here is: Why did the Companions let the pictures in Khosrow’s hall remain? Those who disagree with us are incapable of answering this. One of them says that we should only follow hadith and disregard the actions of the Companions. This is strange, for is it imaginable that the Companions would randomly follow their own inclinations? Aren’t the actions of the Companions and their sayings an interpretation and illustration of the teachings of the Prophet PBUH? We have not abandoned the Prophet’s sayings PBUH, and neither did the Companions, may God be pleased with them. Rather, they understood the texts in a way different from those who disagree with us. It is the Companions who narrated those hadith narrations to us. And it is they to whom those narrations were directed, therefore their understanding takes precedence in matters of dispute. And the ijmaʿ [consensus] of the Companions is one of the acknowledged sources of Islamic legislation. Additionally, all of the 73 groups claim to follow the Quran and the Sunnah, but the distinguishing characteristic of al-firqa al-nājiya [“the group that attains salvation”, i.e. from the hellfire] is that the group follows the Companions of the Prophet PBUH.

As for the claim that during all of those years they were too busy [to destroy the paintings and statues], I do not think the person saying that believes it himself, it is just that he cannot find a better argument. Was it too difficult for Saʿd bin Abī Waqqāṣ or one of the rulers after him to command one of the slaves to repaint those walls that had pictures? As for denying that the Companions had seen the pictures, this is obstinacy and denialism, for Khosrow’s hall is the biggest building in al-Madāʾin, and the fact of the Muslims entering it is a well-known and multiply-transferred piece of information that no one denies. It was full of pictures and statues and poems were written about it. This same hall became the center of government in Iraq until the building of the city of Kūfa was finished.

The sheikh Dr. Aḥmad al-Ghāmidī answered this criticism by saying: “These pictures and statues were not worshiped aṣnām, they were rather figures depicting past events, and perhaps there was a lesson or benefit in letting them remain.” I say that it might be so, and using the fact of their not being worshiped in his reasoning is the same as what I say. He also said: “Fifth, the prohibited thing is the creation of pictures. As for the narration from Ali, may God be pleased with him, regarding the destruction of figures, it refers to three-dimensional statues.” But they weren’t pictures only; the hall of Khosrow was full of statues as is the wont of kings. Ali himself ruled Iraq and did not order the destruction of any of its statues.

The mention of Khosrow’s palace is merely an example. In reality great statues have been allowed to remain not only in Khosrow’s palaces but in [the rest of] Iraq, the Levant, Egypt and Persia. Yes, certain worshiped statues were destroyed in Sindh [a province of modern-day Pakistan] and Transoxania when the Companions discovered peoples who worshiped them, as happened in the Arabian peninsula itself. But other than these, then no. A comical event was that one contemporary caller for the destruction of statues claimed that the Pharaonic statues had been buried in the sand and were not visible during the time of the Companions! Saying the in fact they hadn’t been seen until the past two hundred years. In this saying is negligence toward the books of history, for history books are full of information regarding the familiarity of Muslims with these statues. Al-Jāḥīẓ (who was a contemporary of the imams Mālik, al-Shafiʿī and Aḥmad) enumerated the wonders of the world, saying in his Ḥusn al-Muḥāḍara (3/65): “The ṣanam [statue of religious significance, singular of aṣnām] of the two pyramids is Balhawīya, also called Balhunayt [?] and called Abū l-Hawl by the common people. It is said that it is placed there as a talisman so that the sand would not overcome the Giza.” Yaqūt al-Ḥamawī in his Muʿjam al-Buldān (5/401) says: “On the corner of one of them (meaning the pyramids) there is a great ṣanam that is called Bulhayt [?]. It is said that it is a talisman for the sand so that it would not overcome the area of Giza. It depicts a human head and neck, and the top of its shoulders are like that of the lion. And it is very large. It has a pleasant appearance, as if its creator had recently completed it. It is painted a red color that survives to this day despite the great length of time and the distance of the years.” Also see the words of Ibn Faḍl in Masālik al-Abṣār (1/235) and the words of al-Baghdādī in al-Ifāda (p. 96).

The number of the Companions who entered Egypt was greater than three hundred, as al-Suyūṭī confirmed in Ḥusn al-Muḥāḍara (1/166). The first city they besieged was ʿAin Shams [today a suburb of Cairo] as is mentioned in Ibn Kathīr’s al-Bidāya wa-l-Nihāya (7/98). It is filled with large statues as ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādī mentioned in the sixth century [of the hijra], saying in his travelogue (p. 96): “Of that [type?] are the antiquities in ʿAin Shams. It is a small city the ruins of whose surrounding wall are visible, it appears that it was a place of worship. In it there are enormous statues carved from rock. The length of a statue is around thirty cubits, and its limbs are proportionally large. There is much writing on those rocks and figures of humans and animals of the unintelligible [ancient Egyptian] writing.” The Companions resided in al-Fusṭāṭ [today part of Cairo] and Giza, which are very close to the pyramids. It is worth mentioning that the pyramids themselves were covered in the language of the pharaohs, some of whose letters are in the shapes of birds and animals. Al-Baghdādī says about the pyramids (p. 92): “Upon those rocks there are writings in the unknown ancient pen, such that I did not find anyone in the towns of Egypt who knew of anyone who understood them. There is a great amount of these writings, such that if what is written was transmitted to pages of books, they would take up ten thousand pages.” Al-Masʿūdī mentions similar things in his history (1/361) and Ibn Taghrībirdī in al-Nujūm al-Zāhira (1/41).

Judging from all of that, the Companions who entered Egypt certainly saw the Sphinx and the pictures on the pyramids. These in addition to the statues in ʿAin Shams, about which there is no doubt that they saw them after its conquest and their entering the city. Denying that they saw them is obstinacy. These, in addition to the statues in the pharaonic cities of Memphis and others. It is more likely than not that they saw these too, due to the great number of the Companions and the length of their stay in Egypt. And it is these about which al-Baghdādī says (p. 102): “As for the statues, the greatness of their number and the enormity of their size, it is a matter that is beyond description and computation. The accuracy of their shapes, the meticulousness of their aspects and the carving upon them of natural facets is in truth a matter for wonder.” Despite that, we have not seen them [the Companions] destroy any of them. So were the Muslims incapable of destroying those statues? This is absolutely false. That is because they were able to destroy the fortress of Babylon and the walls of Nahavand in Persia, and they drilled through [the walls of] many of the fortresses they besieged, which were great fortresses that had armed guards that shot arrows at the Muslims during their drilling and destruction of them. Couldn’t they at least disfigure the faces of the statues? If this saying [that the Companions were unable to destroy the statues] is not an insult to the Companions then I do not know what is. Is it conceivable that non-Muslims were capable of building while the Muslims incapable of mere demolition? This is impossible.

To summarize, it is not permissible to hang any picture (including photographic pictures) if this has the potential of leading to veneration and the expectation of blessings from it (especially the pictures of sheikhs and leaders). But if one is safe from that (as in the case of one hanging his own picture or that of his child) then there is no issue with it. Any pictures that are in a place unlikely to be venerated, as on pillows and rugs, then there is no distaste for that. The same is true of statues. And there is no issue with children’s toys and dolls, for such things are not venerated. And if statues accomplish a benefit recognized by the Sharīʿa, such as for teaching or training (such as those used in schools for illustration and clarification), then they go from being mubāḥ [not forbidden] to mustaḥabb [recommended], they may even be wājib [strongly recommended or compulsory] in certain cases if they are a means of understanding the sciences and advancing in them. And God knows what the most correct opinion is.

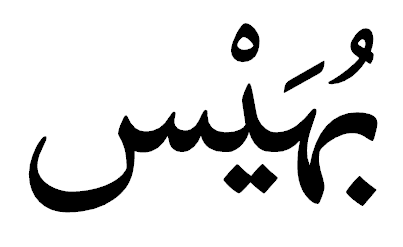

End of the translated article

Translator’s Conclusion

It appears from the above discussion that one can conclude that the issue of taṣwīr is one of context. If a figure is accorded veneration for supposed metaphysical powers, it is prohibited to have it and use it. If it is not, then there is no issue with it. This means that the issue of taṣwīr is quite irrelevant to the lives of most educated Muslims, who find the idea of venerating a picture or statue absurd.

The issue is very similar to that of music (which I discuss here):

- Neither taṣwīr nor music are mentioned in the Quran.

- Neither are clearly and unequivocally prohibited by a command of the Prophet PBUH.

- There is no good logical reason for prohibiting either; both have good and wholesome uses that do not cause any difficulty to the conscience or repugnance to one’s sensibilities.

- Both of them are associated with highly sinful activities; taṣwīr with the worship of idols, music with maʾāzif (wild parties involving wine-drinking and half-dressed women), so that a Traditionalist wishing to be safe from sin would have a strong incentive to stay away from both regardless of any expected benefits.

- The majority of the world’s Muslims refuse to take either prohibition seriously.