There is no reason why we can’t make a perfectly legal, and better, alternative to platforms like Popcorn Time

In my previous essay Why Digital Piracy is Ethical and Necessary I discussed why there are no proper digital libraries: publishers pretend that digital goods cannot be sold. They demand continuous rents for digital products they give to libraries, making things like ebooks costlier (and for more difficult to lend due to various licensing clauses) than printed books. In this essay I will discuss an alternative model for digital libraries that will accomplish the following:

- It will accomplish everything the digital piracy scene currently accomplishes: providing a very low-cost method of conveniently accessing digital products.

- It will help break the power of the publishers by bypassing them: the library becomes an alternative platform where creators can offer their products for “sale” (as will be explained).

- It will help create an open alternative to the “walled garden” approaches of Steam and Kindle Unlimited.

- It will help support creators by creating a highly convenient method for people from around the world to pool their funds in order to buy the products they need.

This is how the Universal Digital Library works: When the Library buys a copy of a digital product (we will use the example of an ebook), it buys the right to lend out one copy of this ebook to one user at a time for two weeks. If two library users want to access the same ebook at the same time, the Library pays for a second copy of the ebook to lend out to the second user. Once two weeks are over, the ebook is “returned”, meaning that it is deleted from the user’s computer by the Library program. Once it is returned, the ebook can be lent out again to another user.

In this way, the Universal Digital Library recreates the way a traditional, real-world library works. It treats digital goods exactly like physical goods. An ebook is just like a print book: the Library has to acquire one copy for each user. If there is a bestseller that thousands of people want to read at the same time, the Library will need to pay for thousands of copies of that book if it wants every user to read it immediately. If the Library cannot afford to pay for thousands of copies, users will need to join waiting lists as in a real library.

This creates an interesting economic effect: a digital product can only sell as many copies as there are people who want to use it simultaneously. If the maximum number of Library members who want to read your ebook is 1000 at the ebook’s most popular phase, and if the Library buys 1000 copies to satisfy all members, from then on the sales of the ebook will drop to zero since every member that comes afterwards will have access to one of those 1000 copies to borrow (once the members start “returning” them).

This, of course, means that ebook creators will have to price their ebooks very high in order to make a profit, since the Library gobbles all the copies it needs until it stops buying. And that is fine, as I discuss below.

Major Features of the Library

A Self-Publishing and Fundraising Platform for Digital Creators

The Library will have a self-serve system for ebook creators, video game makers, software makers, filmmakers and the creators of all other kinds of sell-able and lend-able digital products. If you write ebooks, you can upload the book to the library, set your price, then let the users start borrowing it. The Library will have a pool of money that it uses to buy copies of products that users borrow. The Library will need an algorithm to decide when to buy books: it will take into account the demand for it and the book’s sale price. If Stephen King wants to put his latest book on the Library, he can price each copy at $1,000 USD. For every Library member who joins the waiting list for that book, the Library assigns a certain portion of funds to buying a copy. In order to reward more affordably priced products, the Library can use the following algorithm to decide how much funds to allocate for buying each product:

for each member on the waiting list, during each funding round, assign this amount in dollars to the book's buying fund: 1 / square root of the sale price

This algorithm is designed to reward affordably priced products: the amount of funds assigned to each product decreases the higher its price is

So if a book is priced at $1,000, 1 over its square root is 1/31.6, or $0.03. This means that for every member who joins the waiting list for Stephen King’s book, the Library assigns $0.03 to buying it during each funding round. A funding round could be a daily thing: every day the Library distributes all its income (from donations and subscription fees) over all products on members’ waiting lists. So if there are 100,000 members on Stephen King’s book’s waiting list, that means 300,000 cents will be assigned to its buying fund per day, meaning $3000 per day. This means that the Library acquires three new copies of the book every day. Members will also be able to donate specifically to buying a certain product. So those 100,000 members on the waiting list may donate thousands of dollars daily to acquire more copies. In this way, the Library enables it members to pool their resources to acquire the products they want (if you wonder why anyone would want to donate, read on).

King may realize that he can make money faster by lowering the price. If he prices the book at $250 instead, that would mean $0.06 per user on the waiting list, amounting to $6000 per day. But that $6000 will now buy 24 copies every day. Within a month the Library will have 720 copies of the book. If King prices the book at only $10, the Library will pay out $31,000 per day, amounting to 3,100 copies bought per day. Within a month it will acquire about 100,000 copies, pay out about $1 million to King, and stop buying the book altogether since all possible demand is now met.

But when it comes to non-bestselling writers, they will have to price their books lower in order to make sales, since the waiting list for the book will be much shorter. Let’s say you write an ebook on repairing cars. You can upload the ebook to the Library and price it at $100. For each member who joins the book’s waiting list, 1/10 USD, or $0.10, will be assigned per day to its buying fund. Since the Library serves the entire world, 1000 people may simultaneously want to borrow the book at any one time, meaning that eventually the writer may sell $100,000 worth of the book. Each day the Library will assign $.10 USD for each member on the book’s waiting list, which equals $100 per day. The writer earns $100 per day for that ebook every day, and the Library acquires one new copy every day (since each copy costs $100). Eventually a point of equilibrium is reached where anyone can read the book without having to join a waiting list since the Library ends up having so many copies of it.

The Viable Photoshop Alternative

The Universal Library will not be for ebooks alone. It can also host anything else that can be sold digitally, such as software. The existence of the Library will actually encourage the creation of a wholly new ecosystem for software. A company may develop a Photoshop alternative, let’s call it Imageshop, and place it on the Library for $1000. The Library will have to acquire one copy of this software for each member who wants to use it. If the software is good enough, it would be no surprise of 100,000 people from around the world have a need for it simultaneously within a two-week period. And that means $100 million worth of copies that the Library will need to acquire in order to satisfy the demand.

Many companies may try to develop Photoshop alternatives to upload to the Library, and the ones that are priced cheaper will be funded more quickly due to the funding algorithm–provided that there is sufficiently high demand for it.

The way the Library will work on the client-side will be like Steam. Library members will “borrow” a piece of software, say Imageshop, which will be installed on their device for two weeks. Once the borrowing period is over, the Library program disables the software unless the Library member can renew their borrow and there is no waiting list. If there is a waiting list, the software may be disabled without being uninstalled until the borrow can be renewed. A member may also be allowed to renew their borrow by making a small donation which would cause them to jump to the top of the waiting list.

A Digital Sales Platform for Indie Films

If you want to make an independent film and sell it on the Internet, your options are limited to a few major companies that will demand a major share of any revenues. The Library can act as an independent movie publishing platform: Filmmakers upload their films to the Library and set a price. Similar to ebooks, high-demand films can set prices like $1000 and expect to make millions of dollars through the Library. Lower-demand films can set lower prices.

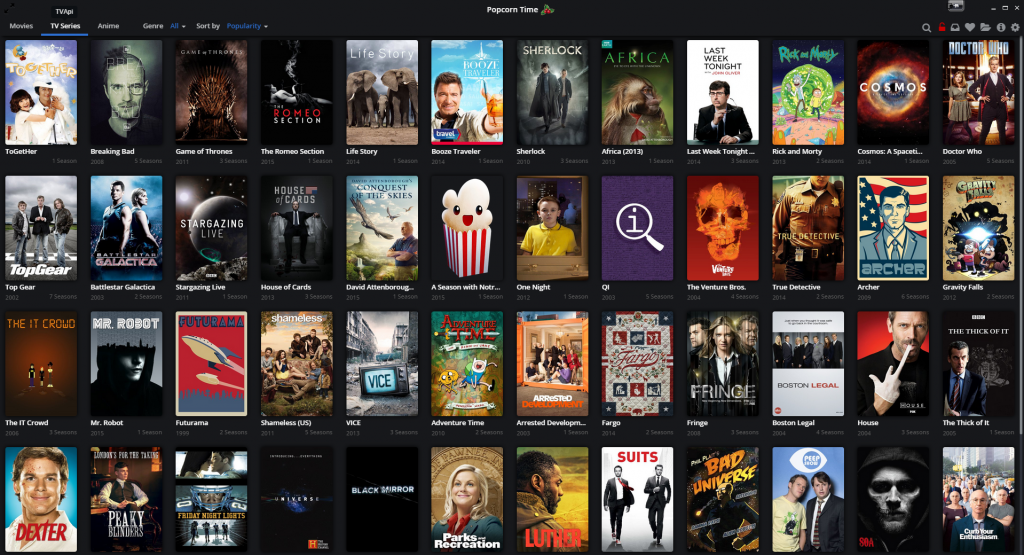

A Democratic Steam Alternative

Steam on my Linux desktop

Steam is Valve Corporation’s famous platform for buying and installing video games. Steam continues the anti-consumer traditions of the publishing industry but maintains a major user base due to its many convenient features. The Library can function as a Steam alternative: just like in the case for software, users can borrow games and play them for two weeks on their machines. The Library can function as a funding platform for independent video game companies: they can upload their game, set a price, and let the Library members decide (through joining the waiting list) how much the Library will spend on acquiring copies of it.

Ending Apple and Google’s App Store Walled Gardens of Garbage

Apple and Google’s approach to smartphone apps is “we and the publishers extracting every penny that can be extracted from consumers.” Google especially has made one of the most unusable app stores in its attempt to control which apps users buy. The Library can function as an app borrowing store where the same economics as those for other software will be at play.

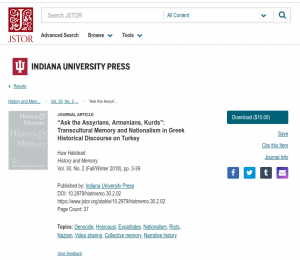

Ending the Absurdity of Scientific Paper Pricing

How would you like to pay $15 to read a single article?

Today reading a 20-page scientific paper often costs $30 or more, making them unaffordable to independent researchers and encouraging the use of pirate platforms like Sci-Hub. The Universal Digital Library can democratize the scientific publishing world and allow researchers to pool their funds for convenient and low-cost access. Similar to ebooks, papers can be priced according to demand. A newly published paper that thousands of people will be interested in reading at the same time can be priced at $100 so that it earns about $100 per day from the Library. Lower-demand papers can be priced at $30 and still make thousands of dollars for its creators.

Ending Publisher Gatekeeping and Walled Garden Behavior

The promotional home page for Amazon’s rather limited Kindle Unlimited platform

The Library can act as a worldwide publisher that connects creators with consumers, making publishers unnecessary. Platforms like Kindle Unlimited are somewhat nice for reading books, but they are still extremely handicapped and consumer-unfriendly:

- Amazon and publishers together decide what books to place on the platform. Users have no voice.

- Amazon can arbitrarily remove any book it wants from its platform

- Paying $10 a month to read a limited selection of books does not make sense unless you are the ideal Platonic consumer who only reads what major publishers dump on them (there is also a large selection of mostly sub-par works by unknown writers).

The Universal Digital Library will be the common-sense alternative to Kindle Unlimited. It will cost much less, it will break the power of publishers and middle men like Amazon, it will empower creators, and it will empower consumers by offering them full-featured versions of the products rather than highly stripped down and limited versions. Amazon’s Kindle Cloud Reader does not allow me to copy a single sentence from books I’m reading.

Kindle Unlimited is about turning ebooks into cable TV: Amazon and its friends get to decide what you can read and how you can read it.

If like me you are interested in making the world a better place through long-term-oriented projects, then you will see the Universal Digital Library as the wholesome, pro-humanity, creator-friendly and consumer-friendly alternative to absurd walled gardens like Kindle Unlimited.

The Two-Week Borrowing Period

I made a few mentions of a two-week borrowing period above. Such a period will have to be enforced just like in a physical library in order to allow members to have the time to use the digital products to their hearts’ content. The two-week borrowing period is also very important for creators since it decides how many copies of each product the Library will need. Since we are trying to recreate a physical Library in digital space, a two-week period seems sensible. However, just like in a physical library, users will be able to “return” their copies prior to the expiry of their borrow period.

How the Library Gets Funded

The Library will get funded through donations and possibly a low monthly subscription fee. The goal of the Library should be to make digital products accessible to those who cannot pay for them the ordinary way, so a free subscription plan may also be offered. The Library may also earn money through advertisements by recommending products to members, although the non-democratic nature of this always makes it a questionable practice. But if ads are necessary for the Library to exist or can make a significant contribution to improving it, then I believe they are justifiable.

We Can Make This Right Now

The Universal Digital Library does not have to wait for any breakthrough or legal change. It can be created right now. It will of course need to invite creators to upload their content according to the Library’s terms:

- One copy for each simultaneous user.

- The Library keeps the copy forever. Once it buys one copy of Imageshop, it is exactly the same as a physical library buying a physical book. The publisher has no right to demand it back.

- The Library has the right to infinitely copy each product while paying the full price for each copy.

A single talented programmer will actually be able to build the entire platform. This is something I have thought about doing, but my other projects have so far prevented me.

On DRM

The most difficult part will be implementing DRM (digital rights management) to prevent easily copying and sharing of the content of the Library by unfriendly actors. Now, the Library must take a common-sense approach to this problem: There is no way to prevent all piracy. There should be a minimum DRM that prevents casual users from sharing the Library’s contents illegitimately, but the DRM should not make the digital products less useful. Users should have access to proper PDF versions of books.

At the beginning the Library can function without any DRM. It will be like existing digital libraries like the pirate-made Popcorn Time. If creators can be convinced to upload their digital products without the existence of DRM, then that would be the best solution. DRM is largely about giving creators a false sense of security since users intent on piracy can always find a way. Using a few free and open source Linux tools a person could easily–within just a few minutes–copy the entire contents of a Kindle ebook and turn it into a PDF using Kindle’s Cloud Reader website. There is nothing Amazon can do about this.

The Library makes piracy largely unnecessary, so it is almost entirely a waste of efforts for it to worry about making piracy impossible. The Library’s program on my computer should be like Steam: it should be so convenient to use, and so powerful and rich, that I never have to think about pirating anything.