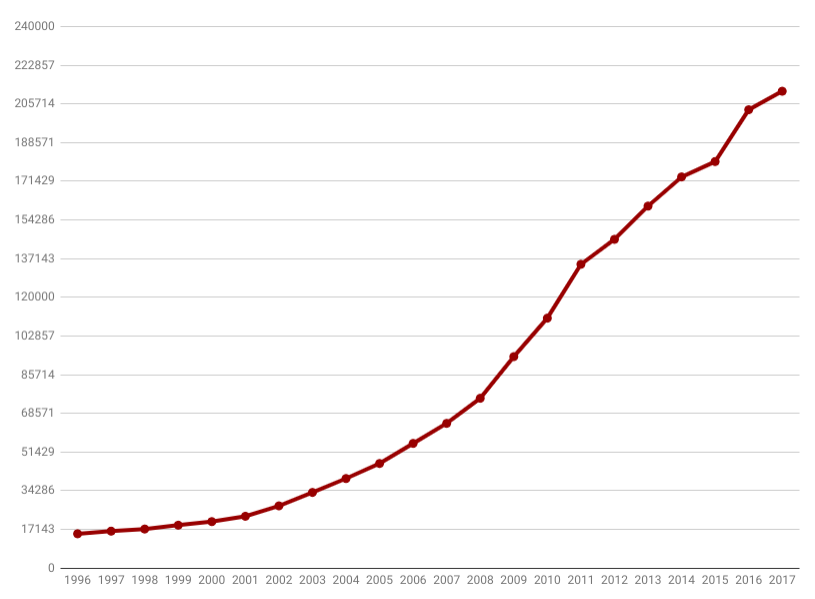

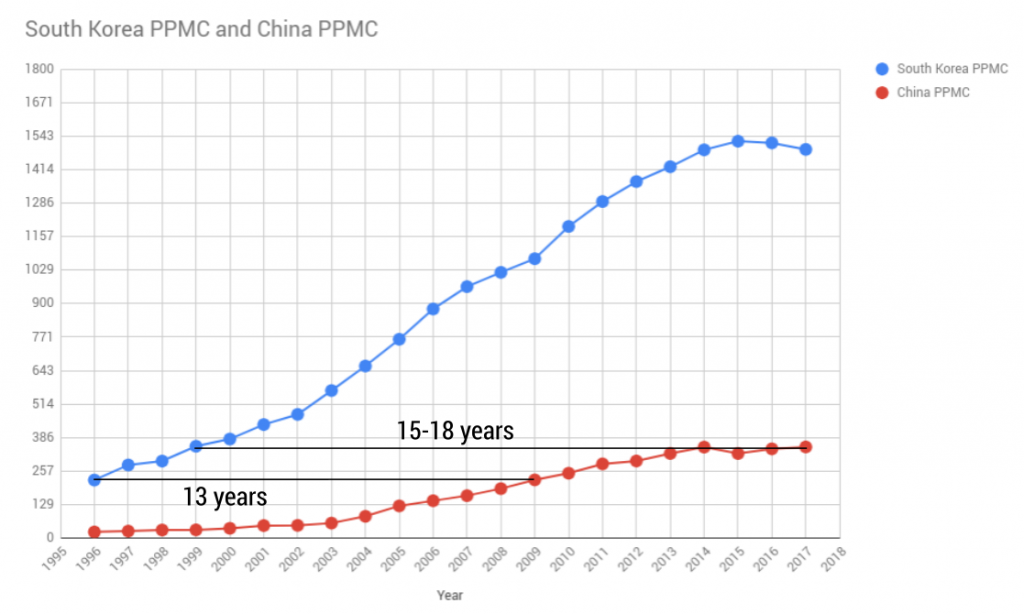

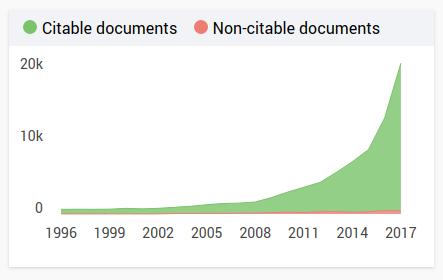

Below is a chart of the scientific output productivity of a number of important countries. Scientific output productivity refers to the number of scientific research papers published by a certain country divided by its population. A higher number indicates that the country is more “scientifically productive”, meaning that it is prosperous and advanced enough to have a large number of citizens busy doing scientific and scholarly research. In 2017, Russia’s scientific output per capita was 561. It published 80796 scientific papers and had a population of 143.9 million. Dividing the two numbers, we get 561, the number of scientific papers published by the country per million citizens. In 2008, Russia published 36419 papers. Ten years later its output had more than doubled, reflecting the fact it is investing heavily in science and has many more professors and researchers busy doing research at universities and research institutions. Still, its output per citizen is still below Iran, and it is almost half of Malaysia. Russia’s scientific output is almost exactly one third of the US, which stands at 1684 papers per million citizens.

The scientific output of the US peaked in 2014 and has only declined since. This is likely a trend that will continue. Russia, in the meantime, will likely continue growing barring a nuclear war, so that by 2028 it will likely reach South Korea’s output level, and soon after that of France (whose output is also declining). The forecast above assumes a 9.35% annual growth in scientific output for Russia, which is what its annual growth was between 2008 and 2017, so I am assuming a continuation of the same trend now since the Russian rulers appear to have finally realized the crucial importance of scientific research for national power and prestige and will likely continue investing heavily in it.

We can expect the scientific output of the United States and Europe to stagnate and decline due to their aging native populations. Immigrants can help stave off some of the fall in output, but due to their generally lower educational attainment, it is unlikely that they will be able to undo the trend unless the countries only allow in highly educated immigrants.

Russia’s 2017 output was where Spain was in 1996 and where South Korea was 2003. We can expect Russia to reach European levels of scientific output by 2028.

Spain: It is interesting to note that Spain is today publishing more science per capita than either the United States or France, despite its population having a median age five years higher than that of the US and two years higher than that of France.

The United Kingdom: The UK’s scientific output is amazing. It publishes almost 1000 more papers per million citizens than many other European countries, reflecting an extremely well-funded and well-organized post-graduate system.

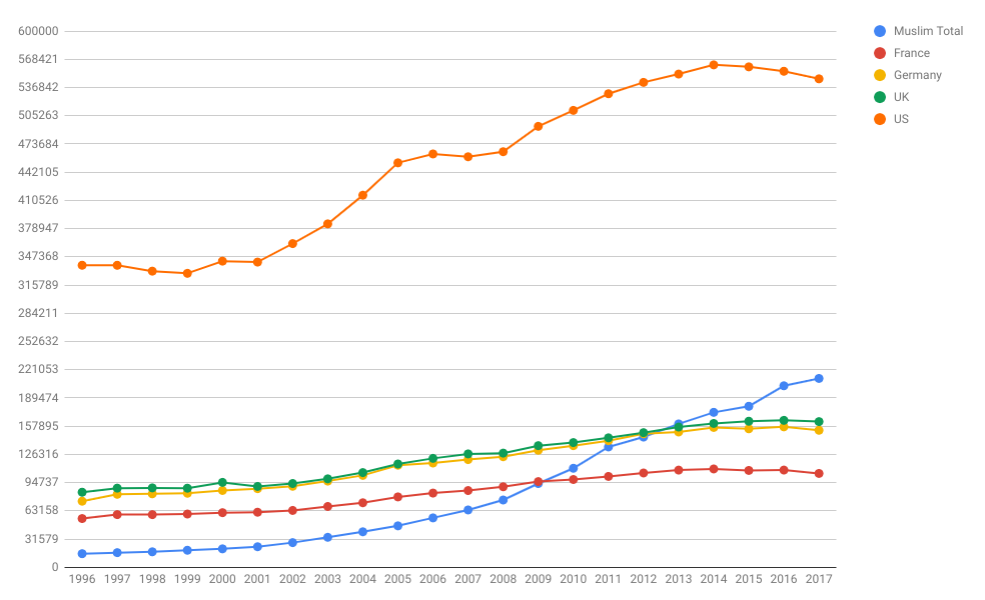

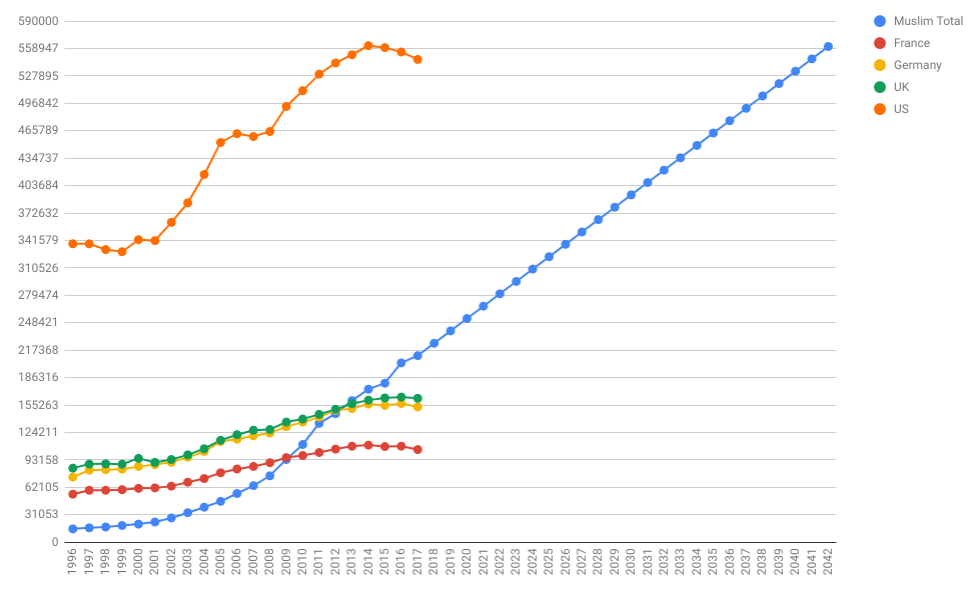

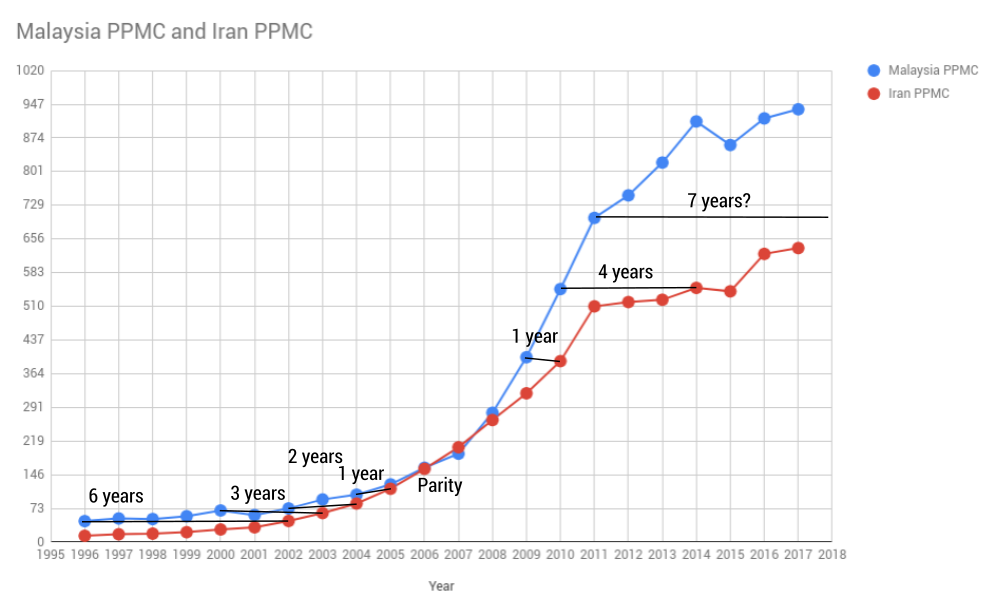

Below is a similar forecast done for Iran. If Iran continues at the rate of scientific output growth it had from 2008 to 2017, it will reach European output levels by 2028. I expect it to slow down its growth and to closely track that of Russia, perhaps being somewhere slightly below it by 2028.

Data from the United Nations and Scimago.