Important note: See the 2025 update below

My new update mentions the latest scholarly views (from 2024) on the origin of Hawramis, and which support my views presented in the original article.

I know some of the names used in this article can be rather confusing, so here’s a brief explanation:

- My last name Hawramani (Hawrāmānī) means “from Hawraman”.

- Hawraman is a small region high in the mountains that spans the Iran-Iraq border in the Zagros mountains.

- Hawraman is the home of the Hawrami (not “Hawramani”) race, an Iranian people similar to Kurds, Tajiks, and Pashtuns (and other Iranian peoples like the Alans, the Bactrians, the Khwarazmians, the Massagetae, the Medes, the Parthians, the Persians, the Sagartians, the Saka, the Sarmatians, the Scythians, and the Sogdians). Hawrami, the name of the ethnicity, can also be spelled as Horami and Avromani.

- The Hawrami people are also known as the Gorani people (not to be confused with the Gorani peoples of other continents). Hawrami Islamic scholars in classical scholarly works are referred to by the title al-Kūrānī, an Arabization of “Gorani”.

Original article:

Regarding the Hawramani people – are they not Kurds? How come you write: “Like the Kurds around them, the Hawrami people are largely Sunni Muslims.” ? Do you consider yourself as Hawramani and not as a Hawramani-Kurd?

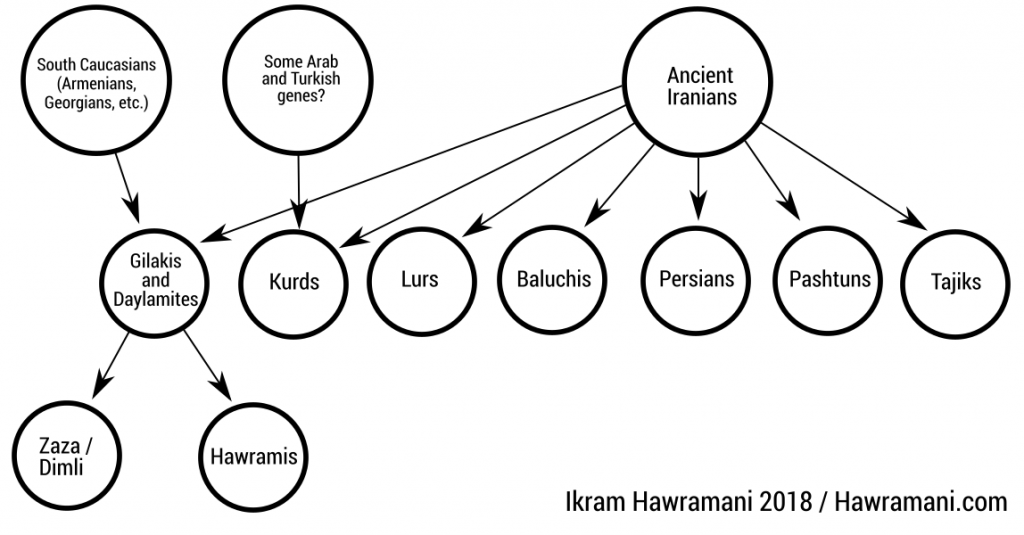

The cultural and linguistic evidence suggests that Hawramis are descended from the people of Gilan, who themselves are a mix of South Caucasians (Georgians, Armenians, etc.) and Persians. Hawramis are closely related to the Zaza people of Turkey, who are also descended from the people of that area. On the other hand, Kurds are a separate race who inhabited the borderlands between Persia, Turkey and Arabia and who probably came from South East Persia.

While Hawramis live among Kurds, they are a different race. Kurds may themselves be anciently descended from the Iranians of Fars province then mixed with Turks and Arabs. Hawramis are descended from the people of the Caspian sea area, who might be a mix of Persians, Armenians and other Caucasian races (such as Circassians) who inhabited the Gilan/Tabarstan area.

Below is a representation of the migration of the original “Kurds” out of Fars province in Iran, perhaps between 600 and 1000 CE (in the BCE era). They settled in that oval area and mixed with Arabs and other original inhabitants.

Below is a representation of the origins of the Hawrami and Zaza people (2025 Edit: the current scholarly view is that the Gorani people were actually the original inhabitants of the areas where they’re found, and were replaced by Kurds). They came out of the south-western coast of the Caspian Sea and settled in Hawraman and Dersim. The origins of the Hawrami and Zaza people were only worked out by scholars in the past 100 years. Vladimir Minorsky spoke of his theory of Hawramis coming out of Gilan, and another scholar whose name I cannot remember worked out the relationship between the Zaza language of Turkey and the Daylam area of Iran. The extreme similarity between the Zaza and the Hawrami languages, their similarity to the Caspian languages (Gilaki, Mazandarani), and their extreme difference from Kurdish, all made Western scholars realize that they are in reality non-Kurdish languages coming out of the Western Caspian.

Another clue for the different origins of Hawramis and Kurds is that Hawramis often look different from the Kurds that live close to them. Tall stature, very pale skin, soft, colored hair and colored eyes are very common among Hawramis while they are not very common among the Kurds belonging to the Jaf tribe or other Kurdish tribes of the area.

For the Zaza people, the word they use for themselves is a clue: “Dimli”, which is an alternative pronunciation of Dilmi, which is a localized pronunciation of Daylami, which means “from Daylam” (the area by the Caspian Sea in Iran).

Update (2018)

I have realized that it is a very sensitive issue for some people whether Hawramis are Kurds or not. To me it’s merely a matter of historical curiosity. Almost all my friends are Kurds and growing up in Slemani, Iraqi Kurdistan, I never made a difference between Hawramis and Kurds. I always tell people that I’m Kurdish when people in the West ask me because I consider myself part of Kurdish history and culture, even though I may not be from the same race exactly. It’s similar to a Volga German from Russia saying he is Russian even though he knows he is descended from Germans.

ladimir Minorsky (1877 – 1966), who lived among Kurds and Hawramis in the first part of the 20th century and had a great love for the people he studied, believed that Hawramis were not Kurds based on the evidence he had gathered regarding Hawrami place names like Gilan and the Hawrami language. Garnik Asatrian, a great linguist of Iranian languages, implies it is laughable to consider Hawramis Kurds because the differences between their languages is so great in his paper “Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds“. Since he is an Armenian, he may have an anti-Kurdish bias, but as a respected academic it is unlikely he would make this claim without good evidence.

If anyone has scholarly evidence that these two scholars are wrong about the matter, I will be happy to see it.

Important Update (2025)

This was originally written as a reply to the comment by Zaza Kurdizade below, who challenged my views. I decided to expand the answer and make it part of the article.

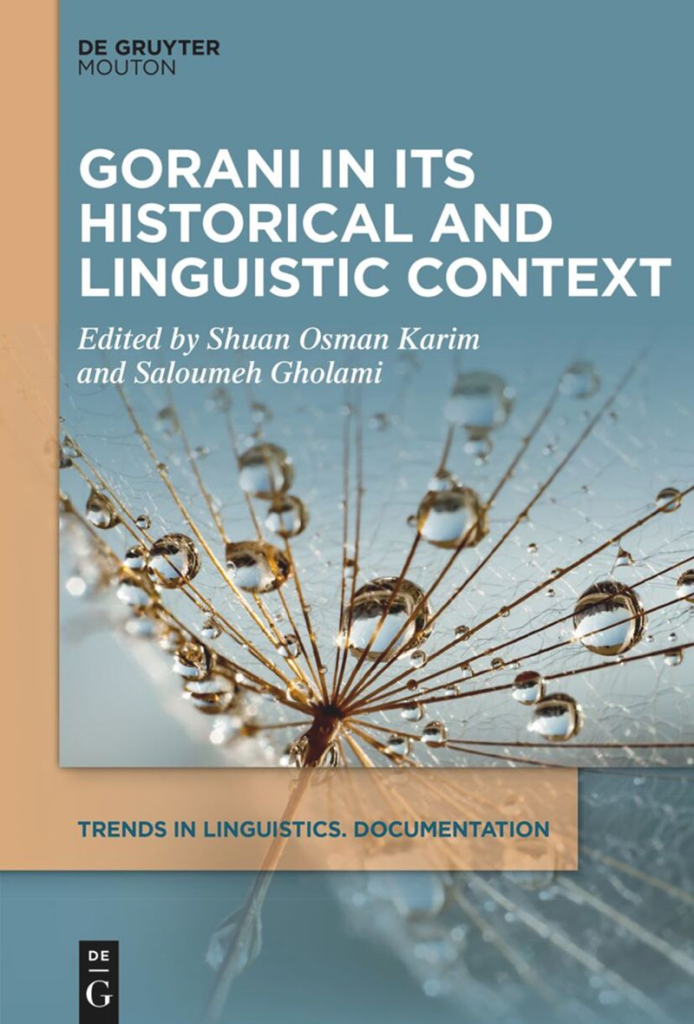

In 2024 the book Gorani in Its Historical and Linguistic Context was published, which is probably the most important contribution to the question of the origin and history of the Hawrami people and their language, with both Western and Middle Eastern scholars (working in the Western tradition). Below are the most important points from this book relevant to our discussion (based on my quick scan of the book, and the help of robot assistants to save time, since this area of research doesn’t really interest me):

- Genealogical Position as a Unique Linguistic Group: The authors classify Gorani as a “unique linguistic group within the Iranian language family”. Gorani is portrayed as a conservative branch of Western Iranian languages, sharing some features with other Northwestern Iranian groups (e.g., Zazaki) but diverging significantly from Kurdish in phonology, morphology, and syntax. For instance, Gorani preserves archaic nominal morphology, such as case distinctions (direct vs. oblique), gender (masculine/feminine), and number marking, which have been largely lost or simplified in Kurdish varieties. Contributors like Karim and Gholami note that Gorani’s nominal system includes unique syncretisms (e.g., feminine singular oblique syncretizing with direct plural), a pattern rare in Iranian languages and absent in most Kurdish forms.

- Isoglosses and Innovations: The work discusses sound changes, verbal stem suppletion (e.g., preserving forms like gn-/ket- ‘fall’ in Shabaki, a Gorani variety), and pronominal systems (e.g., deictic pronouns encoding speaker/listener/far distinctions and animacy) as isoglosses distinguishing Gorani from Kurdish.

- Subgrouping Debates: There is no consensus on a unified “Zaza-Gorani” family, as proposed by some earlier scholars (e.g., Mann and Hadank in 1932). The volume critiques this as based on superficial similarities (e.g., initial w- in certain words) and calls for more systematic studies of shared innovations. Gorani is not grouped with Kurdish in genealogical trees; instead, it is treated as a parallel branch, with Kurdish influence often attributed to borrowing or substratum effects rather than shared ancestry.

- Conservative Traits: Contributors highlight Gorani’s retention of Proto-Iranian elements, such as the active participle in the copula (hen ‘is’ from Proto-Iranian hant- < Proto-Indo-European Hes). Nominal declensions preserve case, gender, and number in ways reminiscent of Middle Iranian (e.g., Parthian), with extensions like -ag (from Proto-Indo-Iranian -(V)kā̆) forming separate classes. Verbal suppletion (e.g., present vs. past stems from different etyma) is more robust in Gorani than in Kurdish or New Persian, where regularization has occurred.

And a quote from the book on the Caspian hypothesis:

[Continuing my summarization of the book:] The consensus hypothesis, supported by the linguistic data referenced in the book and the broader academic context, is that the Gorani people and their language came from a different origin than the main body of Kurdish speakers, and migrated at a different (likely earlier) time to the Zagros region.Based on these findings, [Ludwig Paul] proposed a historical migration theory confirming ‘Zazaki’s origin around the ancient region of Deylam south of the Caspian Sea at pre-Achaemenian times’. In his view, centuries later, probably during the Sasanian period, Kurdish pushed Zazaki in the west more north and northwest, maintaining contact with Azari, Semnani, Talešī, and Caspian languages. Echoing [David Neil] MacKenzie’s (1961) perspective on Kurdish development, Paul suggested that ‘Gorani, on the other hand, soon found itself surrounded by a sea of Kurdish. Eventually, it was reduced to small language islands, exerting considerable influence on southern and central Kurdish varieties’

(Paul 1998: 175)

The historical-linguistic view, which underpins the classification of Gorani as a distinct language, posits that:

-

Different Origin: Gorani and Zazaki are believed to have originated in the Caspian Sea provinces (Northern Iran), based on linguistic features they share with other languages from that region. This contrasts with hypotheses that place the original home of Kurdish further south or southwest in the Iranian plateau.

The difference between the Hawrami/Gorani people and Kurds is further explained by a later wave of Kurdish migration in the Zagros region:

-

Kurdish Arrival: It is hypothesized that at some point, a group of Kurdish speakers migrated southward and “overtook” the existing Gorani-speaking people in the Zagros region.

-

“Overrun” and Displacement: Gorani, despite being once more widely distributed, was “displaced by Kurdish” and other varieties, shrinking to the mountainous pockets where it is found today, such as Hawraman.

Kurdish Migration Hypotheses

The academic work on Gorani supports the dominant linguistic view that the Kurdish language arrived in the Zagros mountains at a different time and from a different starting location than the Gorani language.

Homeland 1: Original Kurdish Homeland

The exact original homeland of the Kurdish language (Proto-Kurdish) before its movement into the Zagros region is a matter of ongoing debate, but the prevalent linguistic hypothesis places it:

-

Original Location: Generally considered to be somewhere in Central Iran or the Southwest Iranian plateau.

-

Time: This migration of the group who would become the Kurds is typically placed around or after the 3rd century BCE. This would be the origin of the dialects that eventually led to all modern Kurdish variations.

Homeland 2: The Northern Zagros Region (The First Kurdish Heartlands)

Homeland 2 is where the Kurdish language first established itself and diversified before spreading south.

-

Geographical Area: The area described as “north of the Zagros” or the original heartland of the Kurdish people is generally understood as the region spanning:

-

The Taurus-Zagros mountain system: Specifically, the areas of Eastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), Northern Iraq, and Northwestern Iran (often described today as Northern Kurdistan and Western Iran).

-

This includes the region stretching from the south of Lake Van across to the west of Lake Urmia, and extending into Northern Mesopotamia. This area is the traditional homeland of the Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish) dialect group.

-

-

Role of Migration: According to one model, the Kurds migrated northward from their Central Iranian origin (Homeland 1) to this northern Zagros area (Homeland 2), perhaps due to pressure from other migrating groups (like the Parthians or the Turks later on).

Homeland 3: Southern Zagros (Gorani-Speaking Areas)

The region where the Gorani speakers lived (“Homeland 3”) became a secondary zone for Kurdish expansion:

-

Movement: From the Northern Zagros (Homeland 2), a group of Kurdish speakers moved southward.

-

Result: This southward movement led to the Kurdish speakers overtaking or settling in the areas previously dominated by Gorani speakers. This process led to the Kurdicization of many Gorani people, resulting in:

-

The formation of Central Kurdish and Southern Kurdish dialects, which show significant linguistic influence (a “substrate”) from the earlier Gorani language.

-

The Gorani language itself being pushed into isolated mountainous pockets, such as the Hawraman region.

-

That’s the most important information I gleaned from the book (along with other sources on the Kurdish migration hypotheses).

Right now to me all of this is merely historical and scientific curiosity. In case you thought I’m only out to upset Kurds, I will now say what will upset many Hawramis: I believe Hawramis are disappearing quickly and within a few generations only a few thousand speakers may be left. And I do not consider this a bad thing.

I care neither about either linguistic, cultural, nor genetic/blood purity preservation. This is not because I am “Islamic”, but because I have an evolutionary and sociological view of language and culture: they’re utilities that serve a specific function in a certain time and place, and once their existence does not add value, but becomes a burden, it either changes or disappears. The Hawrami language, whatever its virtues, is no longer necessary within the new world where Hawramis are no longer isolated from Kurds, but rather are heavily mixed with them. Languages are tools for communication, and the one that makes the most sense in a certain time and place ends up becoming dominant and taking over, and in the case of Kurdistan that language is Kurdish.

Of course I wouldn’t say much or any of this face-to-face with a Kurd or Hawrami. But it is easy to be courageous behind a keyboard, especially when most of the people I know don’t understand English, and even better, don’t care about what I think.

As for Hawrami genes, thanks to assortative mating, the best Hawramis will marry the best Kurds, and whatever genius exists in both races will unite together. Hawramis are intermarrying with Kurds now more than ever, and this is only going to accelerate. I do not know any Hawrami ridiculous enough to reject a suitable woman just because she is not Hawrami. We are all now part of the same culture, the same economic reality, the same demographic and social pressures and constraints, and the same destiny.

My extended family on both sides are Hawrami, but almost all my aunts and uncles are married to non-Hawramis, and among all of them, only one aunt’s family speak Hawrami at home. I understand Hawrami well but cannot speak it because I have never had reason to speak it, so I have no experience in expressing myself in it.

But moving on to my original concern of historical and scientific accuracy, if we use “Kurdish” as a linguistic/genetic designation, then Hawramis aren’t Kurds, despite coming from common Iranian origins, just as Persians aren’t Kurds.

But if we use “Kurdish” as a sociological designation (“those Iranian peoples who live around the Zagros and are neither Persian, Turk, nor Arab”), then you can call Hawramis Kurds.

To me the most accurate way of putting it is that Hawramis are to Kurds as Persians are to Kurds. Think of it like Icelandic versus Norwegian: Icelandic preserves ancient Norse features better due to isolation, while Norwegian changed more through contact, even though both diverged from Old Norse at the same time. One can say “the Kurds known as Hawramis have a different origin from the rest of the Kurds” (using “Kurd” as a sociological rather than ethnic designation). But if this was used as a linguistic/genetic designation (to mean that all Kurds are the same linguistically and genetically), it is like saying “the Norwegians known as Icelanders have a different origin from the rest of the Norwegians.” It is just a silly and pointless statement, trying to force Icelanders into the Norwegian category because of one’s preferred take on history, nationality and race. Icelanders and Norwegians both diverged from Old Norse (similar to Hawramis and Kurds diverging from ancient Iranians), but Icelanders are not Norwegians, and Hawramis are not Kurds, if Norwegian and Kurd are intended to mean a parent group under which Icelanders/Hawramis can be placed.

As for the matter of Kurds being Iranians: Many Kurds will be insulted to be called “Iranian” for the simple reason that they think it means “Persian”. Many are surprised to hear that Kurdish is an Iranian language. Others, more infected with the nationalist myth, will be insulted because they like to believe Kurds sprung out of the ground, some original, mythical race that came into existence by itself. And others like to be considered Indo-European while disliking to be considered Iranian, which is like your hating to be considered your father’s son while liking to be considered your grandfather’s grandson.

The unity of a race is preserved entirely by constraints. Once such constraints are removed (such as political borders), races end up mixing. In 10,000 years there may no longer be any Kurds or Persians; brand new races, created out of the long mixing of existing races, will have come into existence.

So to me arguing and fighting about matters of race and nationality is juvenile. The Internet is full of Balkan young men attacking each others’ races to prove their own race’s superiority. What does this matter in 100 years? What changes the world is real work, real effort, the seeking of truth, the building of what has value. A single great scholar’s efforts is sufficient to put an end to a hundred-year-long debate. This is what matters.

أَلَمْ تَرَ كَيْفَ ضَرَبَ اللَّهُ مَثَلًا كَلِمَةً طَيِّبَةً كَشَجَرَةٍ طَيِّبَةٍ أَصْلُهَا ثَابِتٌ وَفَرْعُهَا فِي السَّمَاءِ (24) تُؤْتِي أُكُلَهَا كُلَّ حِينٍ بِإِذْنِ رَبِّهَا وَيَضْرِبُ اللَّهُ الْأَمْثَالَ لِلنَّاسِ لَعَلَّهُمْ يَتَذَكَّرُونَ (25) وَمَثَلُ كَلِمَةٍ خَبِيثَةٍ كَشَجَرَةٍ خَبِيثَةٍ اجْتُثَّتْ مِنْ فَوْقِ الْأَرْضِ مَا لَهَا مِنْ قَرَارٍ

Have you not seen how God has struck a parable of a good word as a good tree, its root firm and its branches in the sky, yielding its fruit every season by permission of its Lord? And God strikes parables for people so that they may remember. And the parable of a foul word is as a foul tree, severed from off the face of the soil, having no roothold. (Quran 14:24-26)

أَنْزَلَ مِنَ السَّمَاءِ مَاءً فَسَالَتْ أَوْدِيَةٌ بِقَدَرِهَا فَاحْتَمَلَ السَّيْلُ زَبَدًا رَابِيًا وَمِمَّا يُوقِدُونَ عَلَيْهِ فِي النَّارِ ابْتِغَاءَ حِلْيَةٍ أَوْ مَتَاعٍ زَبَدٌ مِثْلُهُ كَذَلِكَ يَضْرِبُ اللَّهُ الْحَقَّ وَالْبَاطِلَ فَأَمَّا الزَّبَدُ فَيَذْهَبُ جُفَاءً وَأَمَّا مَا يَنْفَعُ النَّاسَ فَيَمْكُثُ فِي الْأَرْضِ كَذَلِكَ يَضْرِبُ اللَّهُ الْأَمْثَالَ

He sent down water from the sky, and valleys flowed according to their measure, and the torrent carried swelling foam. And from that which they heat in the fire, seeking ornament or goods, comes foam like it. Thus does God strike truth and falsehood. As for the foam, it goes away as waste, but as for that which benefits people, it remains in the earth. Thus does God strike the parables. (Quran 13:17)