Kak Ahmadi Muftizada: Darwazayak bo Xabateki Nanasraw (کاک ئەحمەدی موفتیزادە: دەروازەیەک بۆ خەباتێکی نەناسراو, Ahmad Moftizadeh: A Gateway to an Unknown Struggle) is a 394-page Kurdish biography of the great Iranian Kurdish leader Ahmad Moftizadeh written by Sarwat Abdullah, apparently published in 2010.

I have been reading all available materials on Ahmad Moftizadeh, since he is one of the few modern leaders who have truly embodied the type of activist, Quran-centered and heart-centered Islam I believe in, and it would be a shame to not learn everything significant that his life can teach. In my view studying the lives (and mistakes) of the previous few generations coming right before us is crucial to making progress.

Origin

It is mentioned that his grandfather, Abdullah Dishi, “came from” the village of Disha (a Hawrami village), which would suggest that Moftizadeh’s family are Hawrami. According to The Last Mufti, Abdullah Dishi’s family were originally from the Kurdish areas and had settled in Disha, meaning that they weren’t originally from this village, and meaning that Moftizadeh’s family are not necessarily Hawrami.

Ahmad Moftizadeh came from Iranian Kurdistan’s religious elite. His grandfather had been given the status of mufti (chief religious law-maker) of all of Iranian Kurdistan, and this title had been passed down to his son (Moftizadeh’s father), and Ahmad Moftizadeh was in line to receive the title himself. Moftizadeh’s father lectured at Tehran University on Shafii jurisprudence, and Ahmad Moftizadeh would go on to lecture there himself later on.

Dreams and childhood

It is mentioned that multiple people around him had dreams about him in his childhood in which they saw him as having a high status. This includes a very old and pious aunt of his when he was 4-5 years old. When he is 8 or 9 a friend of his mother has a dream in which she sees a great army in the city of Sanandaj and she is told that that is Ahmad’s army. She asks if they mean the little boy Aha Rash (a nickname for Ahmad Moftizadeh), and she is answered yes.

Moftizadeh had many dreams of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, in which the Prophet taught him things. Seeing the Prophet ﷺ in dreams is something highly prized by Sufis, whose influence on the area made the population look out for such dreams as well.

At the age of 13 a great officer in the army is invited to his home, so that his family cooks five types of rise and five types of meat. He is disgusted by this, considering it wasteful and thinking of all the poor people who have little to eat, and he decides not to eat anything of it. The aristocratic atmosphere of his home apparently makes him eager to leave it, so that he goes to Iraq to study.

Prison and repentance

After coming back from his studies, he goes to Tehran and is involved in some Kurdish nationalist activity, attracting the attention of the Shah’s secret police (SAVAK).

When Moftizadeh is imprisoned by the SAVAK 1964 for his Kurdish political activism, it is mentioned that he is taken to Evin prison, when in reality he was taken to Qezelqaleh prison as mentioned The Last Mufti. Evin prison comes at a later stage in his life, after the revolution. Later on, on page 53, the book contradicts itself, correctly saying that Moftizadeh was actually at Qezelqaleh.

In prison, in solitary confinement, with death feeling close at hand, he starts to feel guilty about his government job. He worked at a government office where part of his job was to assess and receive taxes from people. While he did his job with conscientiousness, not taking bribes and not cheating people (like other government employees would do), he has the realization that his salary from that job was partially impure, since it was from a government’s unjust taxes on the people.

At first he is too shy to seek repentance from God, feeling that with death so close at hand, the time of repentance is past. He eventually repents, and says to himself, “Even if my (infant) son Jiyan is about to starve to death, I will not use impure money to buy him powdered milk.”

Later in his life, one night his son Jiyan is extremely sick and the only open pharmacy in town is one that is Jewish-owned. He refuses to buy from them, thinking that his money would be used to “buy bullets” for Israel’s terror against Palestinians.

While somewhat extremist (Islam allows one to make exceptions in times of need), his method of thinking of ordinary daily decisions in activist terms is very important and relevant, and quite similar to Sayyid Qutb’s thinking. The spiritual world takes precedence over the material world. He refuses a material good (the feeding of his son, or his son’s health) to maintain a spiritual good (remaining true to God, refusing to be party to any form of injustice, even if it is merely by buying a drug from an entity that might possibly support injustice).

In mainstream Islamic practice, the culture and the clerics come in between the Quran and population. The job of making moral choices was outsourced to the religious establishment, so that morality was not something on the minds of ordinary people. If the mullahs allowed something, it was OK. If they didn’t, it wasn’t. Moftizadeh and Sayyid Qutb’s approach was to take the religious establishment out of the equation; one reads the Quran, understands its moral philosophy to the best of his or her ability, then follows it to the best of his or her ability in everything in their lives.

This is far more difficult, since there are many difficult moral choices the responsibility for which must be carried by each individual, instead of throwing the responsibility on the shoulders of the establishment without giving it a thought.

More dreams

In prison, he has a dream in which he is about 13 years of age and the Prophet ﷺ is teaching him from the Quran. His elbows are resting on the Prophet’s left shoulder, with him looking on as the Prophet passes his right index finger over a book of Quran that he is reciting from. He mentions that this dream put him in a state of joy and ecstasy that lasted for many days, considering it such a great honor from God.

The start of his Quran-focused Islam

So far in his life, Ahmad Moftizadeh had been a classical Shafii jurist, having had a classical education under his father and other scholars in Iran and Iraq.

He has a dream in which he is standing on the rooftop of his childhood home in Sanandaj, when he sees two persons coming toward him from a distance. The persons do not take steps but appear to glide. They stand about a meter and a half from him and ask him to interpret Sura ad-Duha and Sura ash-Sharh (chapters 93 and 94 of the Quran). Instead of trying to interpret these chapters as an intellectual exercise, he starts speaking effortlessly, saying things he had never even thought of before.

He says that as he spoke, he saw the Prophet ﷺ and his followers during what is known as the Meccan Boycott of the Hashemites, in which the he and his followers suffered extreme difficulty. He saw the relevance of the verses he was interpreting to these conditions, as if they were all part of the same story that he himself had lived. He also sees the Prophet ﷺ praying ardently for Umar ibn al-Khattab to be guided to Islam. He says the things he said in his interpretation of these chapters were as obvious and clear to him as 2+2 = 4. When he wakes up, he is completely thunderstruck by the dream, since none of the things he had said had ever before seemed obvious to him.

This dream causes him to completely change his approach to the Quran. Before this, he had the classical approach, what I call considering the Quran a “historical artifact” or a “dead book”. He says:

Before that, when I would look at the Quran, I would look at its meaning as mere Arabic words and sentences. After that, when I looked at the Quran I saw it as a living thing. The way I looked at life, that way I also looked at the Quran.

Strangely, this appears to also have been the approach of Said Nursi and Sayyid Qutb, both of whom also suffered through prison, and both of whom went on to be great revivalists.

Moftizadeh considers this discovery his re-birth, and afterwards would go on to speak of “the old Ahmad’ and “the new Ahmad”, similar to Said Nursi’s “old Said” and “new Said”.

He says that without his discovery of the Quran’s nature, his life would have been empty, and that a hundred thousand lifetimes were nothing compared to that single moment where he discovered the Quran.

Training the vanguard

After being released from prison, SAVAK offers him a professorship at Tehran University in return for softening his rhetoric against the Shah’s regime, which he refuses. He goes back to Sanandaj with his wife and child. He appears to conclude that the best way to spread Islam’s message is to train activists, a vanguard who embody the Quran’s teachings and go on to create change within their own social circles. This was also Sayyid Qutb’s idea.

His non-classical (Quran-focused) approach quickly garners him fame and people start to flock to his house to learn his reformist-activist approach on various issues, such as women’s rights.

He invites a number of faqih‘s (mullahs-in-training) to come to Sanandaj to learn and work on his project, and works hard to buy them a house. He has a highly valuable rug in his own house that he gives away and places in the new house. When asked why, he says, “This was the last artifact I had of my jahili (pre-enlightenment) life, and you are the cause of freeing me from it.”

He starts giving lectures at Sanandaj’s mosques, until he attracts a fellowship of 60-70 people. SAVAK issues a threat against his followers, so that most of the followers leave and only 15-20 people remain. SAVAK approaches him and offers him wealth and protection, and not just for himself but for his followers too, in return for a. not working with political parties and b. softening his stance against the Shah. His extreme poverty and the pressure his extended family puts on him to make him accept this offer slowly makes him start considering it. He wasn’t going to be involved with political parties, so this wasn’t an issue. And what harm did it do to accept not to speak against the Shah?

He says this was the most difficult moral dilemma of his life, since the things offered him were so attractive, and the things required of him so seemingly unimportant. During this, he has a dream that involves the Prophet ﷺ and Umar ibn al-Khattab. The Prophet is about to tell Umar something, starting by “O Umar…”, but Moftizadeh wakes up before hearing it. This greatly upsets him and he starts to look in the books of hadith to find narrations in which the Prophet speaks to Umar in such a manner. Despairing of his search, he goes to the Quran and tries to find guidance in it for his situation, and he finds that in verse 13:17:

He sends down water from the sky, and riverbeds flow according to their capacity. The current carries swelling froth. And from what they heat in fire of ornaments or utensils comes a similar froth. Thus God exemplifies truth and falsehood. As for the froth, it is swept away, but what benefits the people remains in the ground. Thus God presents the analogies.

He sees the Shah and his apparatus as the ephemeral “froth” that is covering truth and justice for a time, but that will surely be swept away by the forces of time. This makes him decide that truth and justice are timeless principles that deserve his full and never-ceasing allegiance, while any request from the Shah and SAVAK for his allegiance should be automatically rejected, since they are the froth who want to cover up what benefits the people. They are nobodies who will be swept away by history, while truth and justice will remain supreme. He goes on to live by this learning for the rest of his life, even after the Shah falls and the “Islamic” Republic is established.

Maktab Quran

Moftizadeh garnered fame in Iranian Kurdistan by his famous speeches, such as the one he gave at the funeral of the poet Suwaray Ilkhanizada. His fearless criticism of the Shah (sometimes comparing him to the Pharaoh of the time of Moses) gave people hope, since the rest of the Islamic establishment was thoroughly hand-in-hand with the Shah’s regime. A Muslim scholar speaking against the Shah was something unknown and highly attractive.

Maktab Quran (“school of Quran”) is the name of the movement/organization he and his friends created, first in the city of Mariwan and later in Sanandaj. The word maktab refers more to a “school of thought” than a physical entity (as pointed out by Ali Ezzatyar in The Last Mufti), a reference to his use of the Quran as a source for a reformist-activist Islam. He did, however, create schools in multiple cities where the Quran and related topics were taught, so Maktab Quran was a physical entity as well.

Revolution (1978)

Moftizadeh’s fame and opposition to the Shah made him a natural leader of Iranian Sunnis at the time of the Iranian revolution. The revolution worried him because he considered it untimely, and was aware of the great possibility for the rise of a new anti-Kurdish tyranny in Tehran (which is what happened).

He believes that if his movement had been given 10-15 years without the Iran Revolution happening, the movement would have been able to bring Kurds to a state where they were ready to be the leaders of revolutionary change, since his goal was to teach people to insist on truth and justice and refuse to (intellectually) submit to tyrants.

SHAMS

After the Iranian revolution, Moftizadeh worked with other Sunni leaders (such as the scholar Abdulaziz Malazadeh from Sistan-Balochistan) to create a unified front for interacting with the Shia-majority revolutionary government, accepting Khomeini’s promises of respecting democracy and pluralism. This unified front was called SHAMS (which means “sun” in Arabic, and was an acronym for shurayeh markaziyeh sunnat, meaning “central council of the Sunnis”). A meeting was held in Tehran in public in which the creation of SHAMS was announced and its details agreed upon by Sunni religious leaders from various areas of Iran.

Naturally, Khoemini and his friends considered this union of the Sunnis a dangerous attack on their establishment, and the Iranian propaganda press went into overdrive over the few days following the meeting, associating the meeting with foreign influence, treason and all the other buzzwords that governments use to describe those who make them feel uncomfortable. Khomeini even gave a speech denouncing SHAMS.

Prison again

Khomeini’s extremist grip on power continued to increase as a number of convenient assassinations removed his more balanced Shia friends from Earth (such as Ayatollah Beheshti). This purging of the moderate Shias cleared the field for him to let his totalitarian tendencies run wild.

A year after SHAMS, the Iranian government cracked down on those associated with Moftizadeh’s Maktab Quran movement throughout Iranian Kurdistan and imprisoned many of them, including Moftizadeh himself.

They held him for ten years in solitary confinement, never allowing a single visitation by his family and friends.

Keeping Kurdistan together

During the revolution (between 1978 and 1981), Moftizadeh worked constantly to bring the Kurds together and have them reach a peaceable agreement with the new government to ensure the rights of the Kurds. The people he was interacting with, the leftist Kurdish parties on the one hand, and the Shia government on the other, were both equally power-hungry, duplicitous and unreliable, so that his efforts were seemingly entirely futile.

Moftizadeh continued to try to work with everyone else in good faith, expecting the best of them, signing agreements with Kurdish party leaders who would go on to change the agreement the next day, adding their own clauses to it that had not actually been agreed upon, or agreeing on one thing then acting another way.

Moftizadeh tried his best fulfill his role as “the leader of Iran’s Kurds” as he was widely considered, but to no good. Would it have been better if he had refused, seeing as the Kurds and the Shias were both totally and utterly incapable of working in good faith together? What is the point of trying to make things work when everyone you are dealing with is corrupt and selfish?

While his political work has generally been considered a failure, his appeals for peace and avoidance of blood-shed may have saved Iranian Kurdistan from having the same fate as Iraqi Kurdistan, with hundreds of thousands of lives lost in a war with the government. It is quite possible that hundreds of thousands of Kurds living in Iran today owe their lives to some degree to his political work.

His fight with the sheikhs and mullahs

I wonder at the people of this town. They have so many mullahs, yet they have managed to remain religious and pious and they have not lost the way of Islam. —Ahmad Moftizadeh

Ahmad Moftizadeh, despite being a classically trained religious scholar and being the son of the chief religious authority of Iranian Kurdistan (and being offered this position himself later on), was a strong critic of the Islamic establishment of his time. The Sufi sheikhs and mullahs had created a comfortable religious aristocracy where the population was made to serve their interests, finding clever ways of extracting money from the poor, such as making farmers take large portions of their harvests to the nearest Sufi establishment where a fat and corrupt Sufi sheikh usually presided.

The mullahs (clerics and preachers who worked at the mosques) weren’t much better, fleecing the population through things like “repairing” divorces, without actually working to solve the roots of society’s issues.

Islam had become a ceremonial religion devoid of its activist message. Moftizadeh considered the religious establishment cowardly and complicit with the Shah’s regime. Not a single leader could be found who dared to speak a word of truth against the Shah’s injustice. Moftizadeh made many enemies by opposing this system, so that some mullahs and sheikhs labelled him a “hypocrite” and scared people away from his circles. Eventually, with his radical honesty and fearless criticism of the Shah despite the dangers to his own life, he became the unchallenged leader of Iran’s Kurdish Sunni Muslims (and perhaps forever broke the hold of the religious establishment on Islam).

In Shia Islam, the clerical establishment claims to have secret powers to interpret Islam properly, powers granted to them as descendants of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. This is highly convenient, since it gives the Shia clerical establishment monopoly power over the way Islam is interpreted and practiced.

Sunni Islam rejects this, saying there is nothing too special about being descended from the Prophet ﷺ. In practice, however, the Sunni establishment acts somewhat similar to the Shia establishment, requiring someone to be part of the establishment before considering their opinions valid. For many Sunni clerics, ordinary Muslims do not have the right to refute a ruling from an establishment scholar. The content of the refutation does not matter; if you haven’t gone through the establishment and do not have their stamp of approval, you do not have the right to speak your mind.

Ahmad Moftizadeh’s teachings took Islam away from the establishment and gave it to each Muslim capable of reading and understanding the Quran.

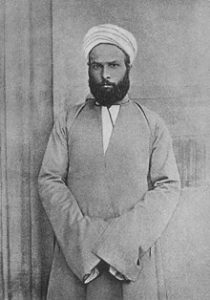

Moftizadeh’s Kurdish identity

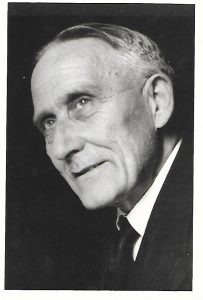

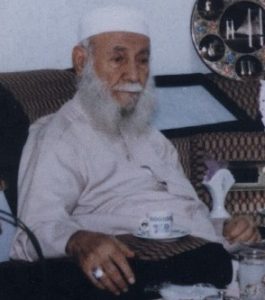

Moftizadeh in Kurdish pants.

Moftizadeh insisted on wearing Kurdish pants, as a way of encouraging other Kurds to not be ashamed of their cultural practices. This was considered unfashionable in his time by other Kurds. They would tell him “You are not a lower-class laborer, so why do you wear that?” He says he replied to such a statement once by saying, “I am a human, and laborers are humans.”

In Sanandaj, the nicknames of kaka (“big brother”), khalo (“uncle”) and mamo (also meaning “uncle”) were used as a way of addressing lower-class people. Moftizadeh came to be called kaka, and he asked his followers to continue calling him this, rejecting honorific titles.

He strongly opposed titles like “sayyid”, “sheikh”, “mala”, “haji”, all of which were used as honorifics for people supposedly religiously or socially superior to others, and all o which could be used to describe himself if I remember correctly. He says these are used to separate one section of society from another, the holier from the less holy, and this makes them un-Islamic and sinful.

Ahmad Moftizadeh considers the Medes the ancestors of Kurds, and the Persians their usurpers. He considers the Persian Empire a permanent force of oppression against Kurds since its inception. He considers Nawroz (the Iranian new year celebration) an imperial and anti-Kurd invention that celebrates the Persian usurpation of Kurdish power.

I have my doubts about this theory, and believe that considering all the Iranian races (Kurds, Lurs, Persians, Pashtos) one race that slowly branched out a far better foundation for building a constructive identity. Kurdish victimhood identity is extremely dangerous, as like all victimhood identities (Zionism, communism, feminism, Shiism) it reduces empathy and the sense of moral responsibility. A victim has the right to more privileges and is held to lower moral standards, and acts as such.

In Moftizadeh’s view, Kurds have been oppressed for 2500 years. In my view, the oppression of the Kurds might very well be a 20th century invention, as Turkish, Arab and Persian nationalism grew as responses to colonialism. Before that, the Kurds were just another subject nation of the Ottomans and the Safavids, and often enjoyed great autonomy, and their noblemen were accepted in the courts of these empires as men of power and status.

Having a single, global humanist identity is so much more beautiful and productive (I should note that I am strongly opposed to globalism, but that is another matter). Western Muslim intellectuals are ahead in this regard, in shunning racial and nationalist identities. But Moftizadeh was a product of his time, and at that time, the issue of Kurdish identity was a matter of top priority, since Persians by and large considered Kurds a backwater nation that should be Persianized for their own good. Moftizadeh’s response was to fight for Kurdish identity, saying that Kurds had as much right to exist and exercise their language and culture as Persians.

The Umayyads

Moftizadeh considers the Umayyads the root cause for the loss of the original “true” Islamic caliphate, and says things mirroring the Shia view on them; that Abu Sufyan’s conversion to Islam was not true and that Muawiyah was on the whole an evil ruler. Since he brought back the old aristocratic system, threw out the shura system of democratic rule, established a dynastic monarchy, and built a palace in which he lived in luxury, for Moftizadeh this is sufficient evidence to consider him evil and corrupt.

Personally, I doubt there is sufficient evidence to conclusively rule that Abu Sufyan or Muawiyah weren’t truly good people. They may have liked wealth and power and worked for it, but so do many other Muslims. They weren’t perfect, but this does not mean that they weren’t on the whole reasonably good people.

Moftizadeh’s anti-Umayyad stance comes from his extreme anti-aristocratic views and his dislike for the Sunni-Shia divide for which he holds the Umayyads responsible.

I believe a more balanced and sophisticated approach is needed when it comes to the historical facts of the matter. As for the religious division issue, focusing on history is not going help matters. The Shia establishment will continue promoting the Shia vicitmhood narrative, since this is important for maintaining power and relevance.

Equality and Marxism

Moftizadeh says “An Islamic society is one in which there are no (social) strata,” advocating for a radical equality among the population, from the ruler to the lowliest laborer (using the example of the Rashidun caliphs to explain what he meant). Some mullahs said that he was becoming a communist with his calls for equality. In response, he instead make a powerful critique of communism, recognizing its feudal nature. He says that communism is actually aristocracy taken to its most obscene extreme, where the central government becomes the unquestioned lord and the entirety of the population its lowly servants.

He strongly disliked the undue respect that government officials received. In one Islamic gathering he sees that a section of the best seats have been reserved for officials. He goes and sits there, to set the example that officials should not be treated specially. When officials visit his home, he is harsh and unfriendly with them. On the other hand, he treats the lower classes with the utmost love and respect.

Regarding the problem of nepotism, ever-present in the Middle East, he says:

Anyone who in his or her dealing with a government official gets preferential treatment because of family ties or other things, and he or she accepts this treatment, they have done injustice.

And on respecting the lower classes:

How miserable is the person who works in the name of leading a religious movement and dislikes meeting the poor, while exulting at meeting the rich and powerful.

His manners

Some of his followers suggested that he should get bodyguards, since they feared for his safety with his great fame and high status. He rejected this, saying that he is no better than the Rashidun caliphs Ali and Umar, who never had bodyguards. He says that one must go among the people, like the prophets used to, that separating himself from the people would automatically make him a failure.

When out, his friends suggest using a taxi to go somewhere (considered a luxury form of transport at the time), he refuses, saying “Why can’t we go like the rest of the people?”

After his release from prison (and close to his death), he was extremely sick from cancer and his body broken by the torture he had received under the Iranians. At one point he was receiving visitors, with everyone sitting on the floor as it is customary in Iran, and as he himself tried to sit, he suffered extreme pain since he couldn’t sit comfortably on the floor. Some offered to bring him a soft cushion to sit on, but he refused, saying, “A sick person can relax as needed when resting, but when among the people, he must behave like the people.” His meaning was that his sickness did not give him the privilege of acting differently and being catered to. This was part of his extreme insistence on equality and “not separating from the people”.

At one point, one of his followers opens a car door for him as a show of respect. He tells them to close it, to go sit themselves, and says, “Do you think I don’t know how to open car doors?”

He sees that someone refers to him as “dear kak Ahmad” in writing, and tells the person not to attach any title to him, even if it is merely “dear”.

One of his followers, who goes on to be killed by the Iranian government, explains that the reason why Moftizadeh attracted such a devoted following was that he truly embodied the three points mentioned in this verse of the Quran:

And who is better in speech than someone who calls to God, and carries out wholesome deeds, and says, “I am of the Muslims”? (The Quran, verse 41:33)

- Moftizadeh called toward God, toward submission to Him and freedom from submission to all other authorities and powers. He never worked for political power or for recognition, he never called for some group of his own.

- Moftizadeh worked to do good deeds day and night. He was a leader in applying the Quran in his own life, and this could be seen everywhere in his manners and actions.

- His stance always was “I am of the Muslims”, which this student of Moftizadeh interprets as meaning that the person does not separate himself from the Muslims using titles and status symbols. While the typical religious leader was happy to use his status as a bargaining tool for dealing with others in power, and while such a leader usually had a highly stratified organization around him, Mofizadeh not only rejected all of this, but turned the tables; he would treat the supposedly lowliest Muslims with the utmost respect and honor, while dealing harshly with the figures of authority in his town (knowing they were corrupt and hand-in-hand with the regime).

Relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood

Some members of the Muslim Brotherhood have mistakenly claimed that Moftizadeh was a member of their organization. While he had very close relationships with some Brothers, he did not do this out of allegiance to the Brotherhood, but out of his heart-centered approach; he would collaborate and help anyone who appeared like a good person.

He was, near the end of his life, against political work, and he is quoted in The Last Mufti as saying that one who engages in political work is very likely to lose the way of guidance.

Comparison with The Last Mufti

The last 100 pages or so of the book is dedicated to translations of articles and interviews with him published in various Iranian publications in the early years of the Iranian Revolution.

The Last Mufti does a far better job of describing the cultural context of Moftizadeh’s time and the origins of his family, likely due to the fact that The Last Mufti relied on far more many sources than this book does. However, it does contain many interesting details and anecdotes not mentioned in The Last Mufti, so both are well worth reading.

Heroes

Moftizadeh’s (and Sayyid Qutb’s) life shows that people need heroes. Moftizadeh was not the founder of a new school of fiqh and one cannot point to any major work of his. A scholarly skeptic, proud of his own works and education, may look at Moftizadeh’s followers and think “What is wrong with all of these people who glorify this nobody?”

Yet the service that Moftizadeh did Islam has been immense and worthier than the works of perhaps a hundred scholars. By embodying his radical message, he became the message. It is sufficient to mention “Moftizadeh” to any of thousands of Iranian Sunnis to renew their motivation, their hope, their trust in God, their insistence on truth and justice, their bravery.

So while many people belonging to the Islamic establishment will be able to call Qutb and Moftizadeh “nobodies”, it is sufficient to see the effects of these men on their respective audiences to realize that these men did tremendously important things, that they were greater than the thousands of religious clerics who failed to do the same, who preferred silence and comfort to telling the truth and putting their lives at risk.

This is an important realization for me; that Islam cannot revive hearts and cannot cause social change unless it is embodied in certain people, no matter how few. For true, dynamic, activist Islam to exist in a community, that community needs to have its own Qutbs and Moftizadehs who are ready to be crucified for its sake, who tell the truth and stand for justice despite the danger to their own careers and lives.

Without such people, the poor, the oppressed, the marginalized will look at the religious establishment and think, “Look at those pompous idiots who think they are here to bring us salvation while they do nothing to protect our lives and dignity.” This was the attitude of people in Iran, Iraq and Egypt toward the religious establishment until people like Moftizadeh and Qutb appeared, and this is probably the attitude of many Saudi people toward their cowardly and well-fed Salafi scholars who turn a blind eye to the abuses of the Saudi family.

This is also the attitude of many Westerners toward the churches. Churchgoers who are not eager to give up large portions of their wealth to feed the poor and the oppressed in their communities have little right to pretend to be followers of Christ, and fully deserve to be considered out-of-touch and pompous hypocrites who do not really believe in their message.

If you do not embody Islam or Christianity’s radically activist message, don’t be surprised if no one takes you seriously.

Conclusion

Moftizadeh’s manners and story is similar to that of Jesus in the New Testament. He fearlessly embodied his message of radical honesty, of respecting all humans, of working against injustice and tyranny, acting like a wrench thrown into the comfortable decay of the Shah’s Kurdistan.

Moftizadeh was the worst nightmare of every corrupt politician, cleric and faux revolutionary, never accepting to limit his speech against them, never seeking material gain (thus he was unbribable), and treating his followers with far more respect and honor than the figures of authority of his society, whether secular or religious, in this way creating a new power structure that discredited the existing ones and empowered ordinary people to feel as if they had the freedom to question things.

Just like it happened with Jesus, many people started calling for his blood, including the religious establishment he was a part of. His criticism of the Shah’s regime helped topple it, but instead of acting the expected way toward his new Shia masters, silently acceding to them, he continued just like before, speaking his mind, discrediting them, not taking them seriously and focusing on truth and justice above all else.

Moftizadeh represents the ideal Muslim citizen; a good and kind friend of every good and kind person, a peaceful activist who did his utmost to prevent violence, a nightmare to every greedy and power-hungry politician, cleric and aristocrat.

Moftizadeh is a very difficult ideal to emulate. People either choose to be power-seeking revolutionaries who risk some but get a lot in return, or quietist mystics who risk nothing and enjoy a comfortable living. Moftizadeh brings together the difficult parts of both lifestyles and throws away the parts palatable to the human ego; you must be a revolutionary who does not seek power, and a mystic who risks everything. Most humans can either live up to the revolutionary ideal or the mystic ideal, very few can unite the two, because not only is there no personal gain in doing this, there is much chance of personal loss. Moftizadeh did that and suffered horribly for it, but renewed the world with his suffering.