Initial version published in March 2019 as “probabilistic hadith verification”. Formally integrated with information theory and renamed to HadithRank in December 2025.

Abstract for researchers:

At its most basic level, a hadith’s HadithRank is about empirical hard limits; a 50% HadithRank means that the laws of physical reality make it impossible to attain any confidence greater than 50% of a hadith’s chance to be genuine and non-distorted, going by its isnād alone, regardless of how trustworthy its transmitters are. To claim higher certainty is to claim the laws of nature have been broken.

HadithRank is a percentage-based hadith grading system that replaces the subjective ṣaḥīḥ-ḍaʿīf judgments of the traditional science of hadith with data-driven percentages that accurately reflect the level of trust in a hadith that its chains of transmitters warrant. It uses information theory to determine the reliability (“likelihood of integrity” or LI) of hadiths by the analysis of their isnād topologies; the “shape” or configuration of their narrator chain graph taken as an abstract mathematical object. Information theory provides the “grammar” for studying isnād topologies. HadithRank provides the “calculus” for solving them.

With HadithRank, a hadith’s isnād topology is treated as an instance of independent redundant channels in information theory where n independent transmissions of the same message through channels with individual error probability p yield a combined error probability of approximately p^n. Thus without any reference to the various realities relevant to hadiths, by envisioning the elements of a hadith’s isnād topology as abstract/mathematical information-theoretic elements, HadithRank yields reliability scores far more in accordance with the likely empirical integrity of a hadith compared to the (publicly-expressed) ṣaḥīḥ-ḍaʿīf judgments of hadith scholars (the reliability level of individual transmitters is taken into account, as shown below).

The HadithRank algorithm represents the general, scientific laws applicable to oral transmission of texts in the context of hadiths–a least-assumptions “Occam’s Razor” approach regarding the level of trust that it is justified to place in any given hadith given its isnād topology, unless we have more specific information that makes a hadith’s likelihood of integrity stronger or weaker. However, no matter how trustworthy or educated a transmitter is supposed to be, and the nature of the transmission that apparently enhanced the integrity of the hadith they transmitted, since such data about the transmitters itself is subject to corruption and distortion, they must never be given too much weight; the HadithRank results must be given the greatest weight as making the least assumptions.

Similar to the way that Arabic grammar is the only correct way to conceptualize the grammatical rules of the language of the Quran, information theory is proposed as the only correct way to conceptualize the “grammar” of isnāds–not one way to think about them, but the way, so that a creative hadith scholar could have invented a rudimentary version of information theory based on their study of hadith chain graphs.

Introduction

Islam’s hadith literature (reports about the actions and sayings of the Prophet PBUH) is one of the most problematic aspects of the religion, due to the issues concerning the reliability of transmitters; whether they were trustworthy individuals and not fabricators or exaggerators, whether they were capable of understanding the contents of the hadiths they were transmitting (in order not to distort their meanings by mixing up similar-sounding words), whether they had sufficient knowledge and training to know the value of accurately narrating hadiths, and so on, among many other questions that can be asked about each transmitter. Relying on such human transmitters, how do we know if a report going back six or seven generations to the Prophet PBUH truly and accurately reports what the Prophet PBUH said or did?

So far the science of hadith has almost entirely limited itself to verifying the authenticity of hadiths by verifying the trustworthiness of each person in a hadith’s chain of narrators. If all the transmitters are trustworthy, the assumption is that the hadith is ṣaḥīḥ (“authentic” or “sound”). The problem is that a hadith scholar’s own beliefs and biases can strongly affect whether they consider a strange and rare hadith to be authentic or not. A good example is the following hadith in Imām al-Bukhārīʾs collection:

Narrated Abu 'Amir or Abu Malik Al-Ash'ari that he heard the Prophet (ﷺ) saying, "From among my followers there will be some people who will consider illegal sexual intercourse, khazz (a type of clothing), the wearing of silk, the drinking of alcoholic drinks and the use of musical instruments, as lawful. And there will be some people who will stay near the side of a mountain and in the evening their shepherd will come to them with their sheep and ask them for something, but they will say to him, 'Return to us tomorrow.' Allah will destroy them during the night and will let the mountain fall on them, and He will transform the rest of them into monkeys and pigs and they will remain so till the Day of Resurrection."

(Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 5590)

A non-scholar who reads this hadith will be greatly troubled by the implication that the use of musical instruments is a characteristic of misguided and impious Muslims. And since the hadith is authentic and present in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, they will face the difficult choice of either believing musical instruments (and hence all music) to be forbidden in Islam, or ignoring the hadith and going with the commonsense and widespread Muslim belief that music is permissible in Islam.

By introducing probability theory into the science of hadith, treating hadith chain graphs as a mathematical, information-theoretic problem, we gain an extremely powerful tool that enables us to judge just how seriously we should take any particular hadith. This is especially useful in the case of ṣāḥīḥ hadiths that seem to be contradicted by other ṣāḥīḥ hadiths. For example, on the issue of musical instruments we have the following hadith:

Narrated Aisha:

Abu Bakr came to my house while two small Ansari girls were singing beside me the stories of the Ansar concerning the Day of Buath. And they were not singers. Abu Bakr said protestingly, "Musical instruments of Satan in the house of Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) !" It happened on the `Id day and Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) said, "O Abu Bakr! There is an `Id for every nation and this is our `Id."

Sahih al-Bukhari 952

An authentic version of this hadith (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 892 b) tells us that the girls were using the instrument daff (“tambourine”). So here we have the Prophet PBUH approving of the use of musical instruments in his own home, yet the other hadith implies that musical instruments are wicked and unlawful. (One way to get around this contradiction has been to consider daff halal and other instruments haram, a good illustration of the fossilized nature of the methods used in the science of hadith.)

Information-theoretic hadith verification helps solve the dilemma of having to choose between two hadiths that are both judged authentic by hadith scholars by telling us which one is stronger. As it happens, the hadith mentioning the Prophet’s approval of musical instruments is far more “authentic” and believable than the hadith in which he disapproves of them.

In this essay I will use these hadiths on music as an illustration of HadithRank information-theoretic hadith verification method.

I have always been a defender of the ordinary, moderate Islam of mainstream Islamic scholars and teachers, so my offering of this method is not an attempt to break with the mainstream, and in fact I believe it will help defend the mainstream Islam of ordinary Muslims, who know that there must be something wrong with the science of hadith when it purports to prove that enjoying music, or drawing paintings of cats, is prohibited.

Being with the mainstream is not just a consequence of upbringing, personal peculiarities, principles, or some other influence; it is also a rationally justified one. Studies support the idea that broad, independently formed agreement is an indicator that a claim is likely true, and that highly idiosyncratic views rejected by a well-functioning expert community count as evidence against those views (though never as logical proof of their falsity).1 From a Bayesian perspective, if a proposition has been widely scrutinized by competent researchers/thinkers and almost none of them endorse it, that pattern is evidence that the proposition is probably false or at least there is little evidence to in its favor, even though it does not logically rule it out. While intelligence encourages a skeptical attitude and an unreadiness to quickly accept what others take for granted, even more intelligence allows one to recognize that in any trade, craft, or field of knowledge, the traditional ways things are done have become traditional because they align with common sense, make practical sense, and lead to good results.

Within the science of hadith, as the most traditionalist one within the Islamic fields of study (which is only natural, as it is concerned with “traditions”), and one whose task is to fight innovations as opposed to encouraging them, there is neither impetus, nor demand, for an established scholar to create innovative new ways of doing things; they’re expected to vindicate the past not challenge it. A person who does not quite like this way of thinking does not become a hadith scholar. In fact, the last two interesting innovations in the science of hadith were both made in the 800’s by Imam al-Bukhārī (the liqāʾ system, and building hadith collections containing only hadiths that pass a verification algorithm).

In the science of hadith, as in any field of knowledge, the fact that certain views and methods are widely shared among the experts is a strong indicator of the validity of those views and methods. But this is only a strong indicator, not proof, and especially not proof that such views and methods are the best possible views and methods.

There are times when someone who was deeply involved with one field, on becoming deeply involved in another, by seeing the analogies between them, finds new ways of doing things in the new field that are more effective than the traditional ways. And thanks to being both an “outsider” and an “insider” at the same time (due to belonging to multiple fields), they are not so worried about the skepticism and criticism of their new colleagues, and dare to do things in a new way that they know to be better.

For example, Claude Shannon trained in both electrical engineering and mathematics. He realized that Boolean algebra (mathematics) could describe logic circuits (engineering). His master’s thesis, now called “the most important master’s thesis of the 20th century”, showed that switching circuits could implement logic, fundamentally changing digital circuit design.

Gregor Mendel (1822-1884) was a monk, but his university training was primarily in physics and mathematics (studying under Christian Doppler), not the descriptive natural history that dominated biology at the time. Biologists of his era were “insiders” who described species through observation and taxonomy (classifying how things look). Mendel viewed biology through the lens of discrete mathematics and statistics. He didn’t just look at the peas; he counted them like data points in a physics equation. He applied statistical probability to heredity. While traditional biologists were looking for “blending” traits (like mixing paint), Mendel looked for “discrete particles” (genes) that followed mathematical ratios. His work was completely ignored for decades because the “insiders” didn’t understand why a botanist was using so much math. He didn’t care to conform to the descriptive style of the time, leading to the founding of modern Genetics.

There are other important names (Hermann von Helmholtz, Louis Pasteur, Florence Nightingale, James Clerk Maxwell).

In this article, similar to Mendel2, I will try to bring mathematics and probabilities into a field where it hasn’t been seen often before (hadith studies), and by using ideas from Claude Shannon (namely, information theory), I will attempt to show that hadith chain graphs, or isnād topologies, can be treated as information-carrying mathematical objects that can automatically determine a hadith’s reliability without any need for human judgment.

The following features of HadithRank give it the potential to be a cause for transformative changes, even paradigm shifts, in the various fields of Islamic study and thought:

- Empirical and algorithmic methodology – The method relies on systematic data analysis and computational processing rather than individual scholarly judgment, making it reproducible, testable, and falsifiable in ways traditional hadith criticism cannot be.

- Probabilistic rather than categorical – Produces continuous reliability scores (0-100%) instead of discrete binary or tertiary classifications (sahih/hasan/da’if), better reflecting the actual spectrum of evidentiary strength and epistemic uncertainty.

- Making the analysis of hadiths with immensely complex chain graphs into a straightforward problem: Two hadiths of very different levels of reliability can appear similar due to the vastness of their chain graphs, often causing an exaggeration of a hadith’s likely reliability (a lie repeated often enough sounds like the truth). HadithRank transforms the challenging task of analyzing and judging the reliability of such hadiths into a simple matter of applying a recursive algorithm, and thanks to a built-in “bottleneck” feature, the algorithm cannot be misled by the mere extensiveness of a hadith’s chains.

- Transparent and accessible – Makes underlying data, reasoning processes, and reliability assessments directly available for scrutiny, rather than requiring trust in opaque scholarly conclusions.

- Epistemological transformation – Shifts hadith sciences from authority-based knowledge to evidence-based knowledge, from qualitative interpretation to quantitative measurement, introducing explicit uncertainty quantification where tradition provided categorical certainty.

- Democratization of hadith criticism – Transfers evaluative power from the scholarly class to individual Muslims by providing direct access to reliability data, removing the need for intermediation in assessing source authenticity.

- Decentralization of religious authority – Challenges traditional hierarchies of Islamic knowledge production by enabling non-specialists to engage with primary source evaluation using shared empirical tools.

- Fine-grained analytical capability – Enables distinctions and comparisons (40% vs 44% reliable) previously impossible within coarse traditional categories, allowing re-ranking within collections and revealing systematic patterns or biases in historical authentication.

Seeing Information Theory in Hadith Chain Graphs

The solution had been obvious for a long time based on these two facts:

- The true nature of the reliability of hadiths is analog, not binary (a spectrum, not black and white): regardless of claims about ṣaḥīḥ and ḍaʿīf, the reliability of hadiths goes from 0% to close to 100%, and while hadith scholars are essential to determining the reliability of transmitters, it is not up to them to decide which hadiths are better than which; the information is, or must be, already contained in the chains–otherwise such scholars are merely expressing their personal opinions. And if the information is already contained in the chains, there is no need for deciding the reliability of hadiths by making pronouncements about what is ṣaḥīḥ and what is not as if deciding legal cases; there is no need for pronouncements at all. The matter is about strength (a less technical way of referring to LIs/likelihoods of integrity that will be discussed later), not ṣaḥīḥ vs. ḍaʿīf. It is similar to going from seeing all humans as either saints or non-saints to opening one’s field of vision to see varying degrees of worth from the highest downwards.

- There’s an obvious one-to-one mapping between hadith science and information theory, so that a correct information-theoretic approach will derive the strength of hadiths (based on their chains and the strength of their transmitters as researched by hadith scholars) in a rationally defensible and empirically verifiable way. This is not about introducing anything alien into Islamic studies; it is just a more sophisticated form of mathematics already used in hadith science, as in the mathematical equation G = r * (k-u/k) used by hadith scholars.3

There are various concepts in information theory and related fields where the same questions are dealt with, but using different terms:

- Source – The original utterance/event that occurred in historical time

- Message – The specific content of what was said (the information to be transmitted)

- Encoders – The witnesses/transmitters who each encode the event into memory and then into testimony

- Channels – The transmission paths from each witness to the recorder (hadith collector):

- Each witness’s perception → memory → recall → verbal/written report

- Each channel has noise (memory errors, bias, misperception)

- Crucially: the channels are independent (different people, perspectives, motivations)

- Receiver – The recorder in historical time who collects all the reports

- Decoding/Decision – The recorder, i.e. the hadith collector, later scholars and we in this essay who must decide: is the signal authentic?

- Redundancy – The same message transmitted through many independent channels

- Noise – Each channel introduces potential errors:

- Perceptual errors

- Memory decay

- Intentional fabrication

- Miscommunication

- Channel independence – Critical assumption: the witnesses did not coordinate or influence each other

- Signal-to-noise ratio improvement – Each additional independent channel carrying the same signal improves the overall SNR at the receiver

- Entropy/Uncertainty reduction – Each additional independent witness reduces the receiver’s uncertainty about whether the event occurred:

- H(event) before testimony: high uncertainty

- H(event | 8 independent witnesses): dramatically reduced uncertainty

- Capacity – Even noisy channels (unreliable witnesses) can reliably transmit information if you use enough redundancy

- Diversity gain – If the witnesses have uncorrelated noise (different types of biases/errors), this further improves reliability

- Detection problem – Binary hypothesis testing:

- H₀: The signal is false (what the hadith says didn’t happen)

- H₁: The signal is true (what the hadith says happened)

- The independent observations (by individual transmitters) provide a likelihood ratio

- Information accumulation – Each witness adds information content, and with independent channels, information adds (roughly) linearly while error probability decreases exponentially

This is textbook information theory—specifically the principle that redundancy enables reliable communication over unreliable channels, which is one of Shannon’s foundational insights.

This is also textbook hadith science.

By representing the elements of a hadith’s isnād topology as elements in an information-theoretic model, we can reach reliable conclusions about the strength of the hadith–conclusions that do not rely on anyone’s opinion and judgment.

While the technical terms may sound complex, the actual method’s calculations can be done by anyone (at least anyone with some STEM interests), and you can always plug in the isnāds into my HadithGraph tool to get the calculation results immediately without doing any math.

See An Interactive Step-By-Step Demonstration

HadithRank Algorithm Showcase: Press "Next" below to continue.

The HadithRank Algorithm for Hadith Science

Given that hadith authenticity is about strength, not ṣaḥīḥ vs. ḍaʿīf (percentages representing the hadith’s likelihood of integrity, i.e. how likely it is to be genuine and not distorted or fabricated, not just 0 and 1), and given that the strengths of hadith chains can be computed using information-theoretic methods (as will be shown), we can now look at the practical side of the matter.

One does not require a degree in fields that deal with information theory (electrical engineering, computer engineering, some math and CS tracks, or data science and statistics) in order to appreciate and make use of the concepts mentioned here. They are elementary and fundamental concepts that naturally apply to the problems of hadith science, as opposed to niche ideas that have some interesting uses in the science.

All of our calculations rely on an important constant, the attenuation coefficient alpha (α). This constant determines how much less reliable a piece of information becomes as it passes from one person to another across historical time, in the context of the historical realities of hadith transmission and preservation.

“α = 0.6” means the signal attenuates to 60% per hop (i.e. the information’s reliability drops from 100% to 60% when it is heard from a transmitter, as opposed to hearing it directly from the source).

How reliable is the testimony of a randomly chosen single trustworthy hadith transmitter on a scale of 100% reliable to 0% reliable? Obviously their testimony is not 100% reliable, because any human can make errors. And since they’re trustworthy as individuals (their character has been verified by scholars4), it is unlikely that their testimony would be 0% reliable (although in the case of individual testimonies it is possible, perhaps their testimony was made in old age and they mistakenly transmitted a proverb as a hadith and imagined a chain of transmitters for it, confusing it with another hadith, this type of thing–tadlīs–is a commonly recorded phenomenon in jarḥ wa-l-taʿdīl literature).

A hadith’s reliability is not about the reliability of its transmitters alone: A big defect in hadith science is that it assumes that the reliability of a hadith’s chain of transmitters is a function of the reliability of each individual in the chain (along with the fact of their having being contemporaries, or more strict, their having met). In reality, every hadith transmission contains a built-in chance of error; no matter how reliable the individuals, it is very much possible that this one time someone erred and transmitted something in a way that changed a hadith’s meaning, or even transmitted a non-existent hadith. If you tell me that 20 years ago your father said such and such, no matter how trustworthy you are, you may have actually heard that from your uncle. Our work here is to establish a model that makes room for all such possibilities by expressing the logarithmic way the chances of such random errors creeping into a hadith explodes as the chain lengthens.

Determining the attenuation coefficient (= how much trust we put in the genuineness and correctness of a single witness’s testimony) requires a great deal of testing (“calibration”) in order to create a hadith scoring model that aligns with one’s design goals. My goals for the model were to produce scores that satisfied these criteria:

- Proper spread ensuring utility and alignment with educated intuitions: a model where every hadith receives a score of 95% or higher is practically useless, as it blurs the distinction between vastly differing reliability levels among ṣaḥīḥ hadiths. And a converse model that gives hadiths very low values is equally useless. The scores must accurately “spread out” so that some hadiths receive 5%, others 15%, others 30%, and so on, in a way that matches an experienced hadith student/scholar’s intuitions and conscience.

- Empirically plausible coefficient: the scores must reflect what is within the realm of the possible, given what we know of human nature, and of the culture of the time, and the respect given to the Prophet’s statements PBUH and stories about him. This means avoiding attributing superhuman memories to the Muslims of the formative era, or assuming levels of fabrication for which there is no evidence (and good evidence against, as shown in Harald Motzki’s work). All facts considered, the integrity of information concerning Prophet Muhammad PBUH can be expected to be much higher than is true of ordinary oral transmission of rumors and tales (as opposed to ritualized transmission, as in the passing down of poetry or other cultural works), but not so high as to suggest careful, well-developed and widespread transmission practices in the first century intended to preserve hadiths the way the Quran was preserved.

- The model must be able to represent the fact of certain ṣaḥīḥ hadiths being many times stronger than other ṣaḥīḥ hadiths: This might perhaps be the most important criterion. A model that exaggerates scores will give both weaker ṣaḥīḥ and stronger ṣaḥīḥ hadiths high scores, perhaps with the majority above 60 or 70%, so that there is no room for any hadith to receive double the score of another hadith without going above 100%. If the model cannot express the fact of one hadith being four or eight times stronger than another hadith, then it is miscalibrated.

After much testing (the “calibration” I mentioned above), I found that α = 0.6 produces the best results:

- The scores cause no pressure on my conscience that they are being exaggerated to make them align with the culture of the science of hadith, or that they’re being understated to align with supposedly more empirically plausible scores.

- The scores reflect very good spread that align with my intuitions; a hadith receiving 10%, another 20%, and another 30%, are obvious in being members of different classes of hadith when looked at without the aid of the method, showing that there is neither “compression” nor over-spreading.

- There seems to be very good room for representing the fact of one hadith being many times stronger than another, with some ṣaḥīḥ hadiths receiving values below 5%, and some above 60%.

In order to perform calibration, the method (as described below) is used to score a large number of hadiths, trying out different values for α for reach hadith’s score, and studying the result sets. Merely working with the method for a while will also be valuable in showing whether α is too high or too low. Note, however, that working with the method itself will likely cause some reassessments in your existing views about the nature of hadiths, so that your initial view of what α should be may change (as it did for me).

How HadithRank Scores the Hadiths on Music

We can now begin to dive into the actual substance of the method, using the following hadiths on the permissibility (or lack thereof) of enjoying music as our example cases.

Narrated Abu 'Amir or Abu Malik Al-Ash'ari that he heard the Prophet (ﷺ) saying, "From among my followers there will be some people who will consider illegal sexual intercourse, khazz (a type of clothing), the wearing of silk, the drinking of alcoholic drinks and the use of musical instruments, as lawful. And there will be some people who will stay near the side of a mountain and in the evening their shepherd will come to them with their sheep and ask them for something, but they will say to him, 'Return to us tomorrow.' Allah will destroy them during the night and will let the mountain fall on them, and He will transform the rest of them into monkeys and pigs and they will remain so till the Day of Resurrection."

(Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 5590)

A non-scholar who reads this hadith will be greatly troubled by the implication that the use of musical instruments is a characteristic of misguided and impious Muslims. And since the hadith is authentic and present in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, they will face the difficult choice of either believing musical instruments (and hence all music) to be forbidden in Islam, or ignoring the hadith and going with the commonsense and widespread Muslim belief that music is permissible in Islam.

By introducing information theory into the science of hadith, we gain an extremely powerful tool that enables us to judge just how seriously we should take any particular hadith. This is especially useful in the case of hadiths that seem to be contradicted by other hadiths. For example on the issue of musical instruments we have the following hadith:

Narrated Aisha:

Abu Bakr came to my house while two small Ansari girls were singing beside me the stories of the Ansar concerning the Day of Buath. And they were not singers. Abu Bakr said protestingly, "Musical instruments of Satan in the house of Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) !" It happened on the `Id day and Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) said, "O Abu Bakr! There is an `Id for every nation and this is our `Id."

Sahih al-Bukhari 952

An authentic version of this hadith (Sahih Muslim 892 b) tells us that the girls were using the instrument daff (“tambourine”). So here we have the Prophet PBUH approving of the use of musical instruments in his own home, yet the other hadith implies that musical instruments are wicked and unlawful.

The Hadiths Approving of Music

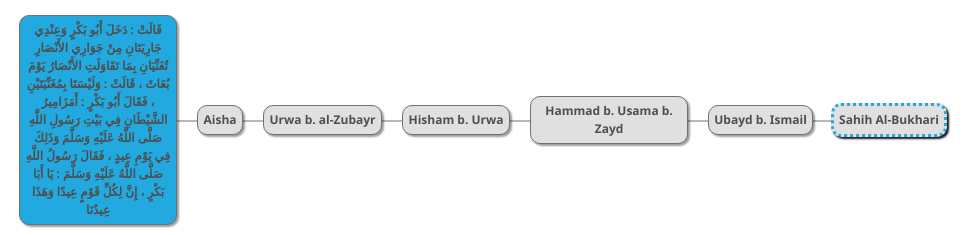

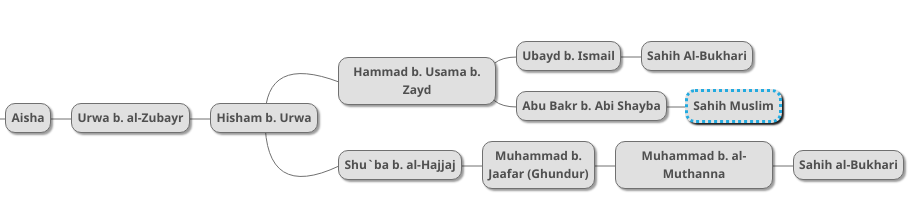

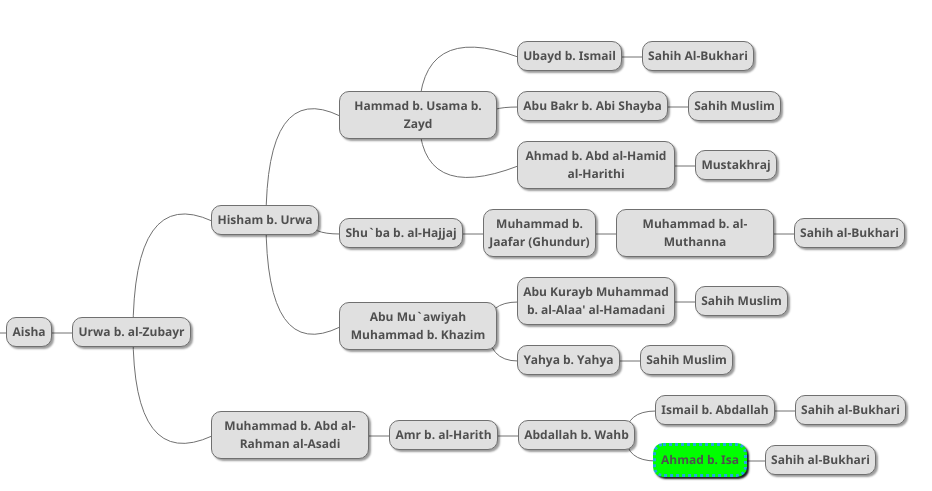

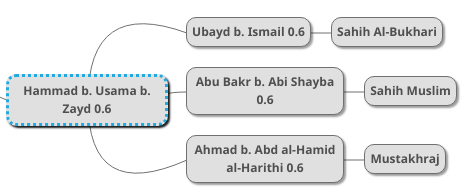

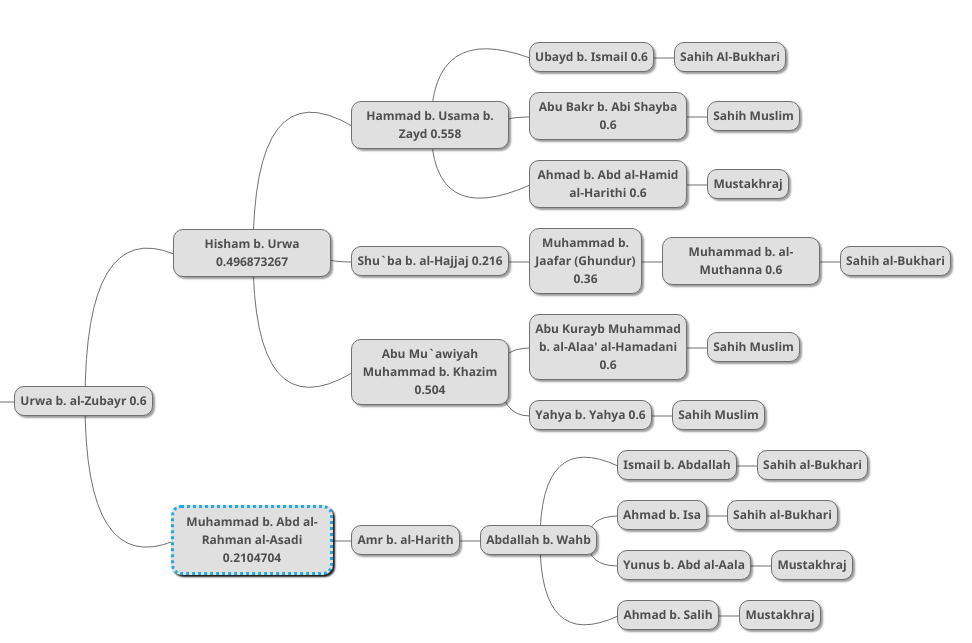

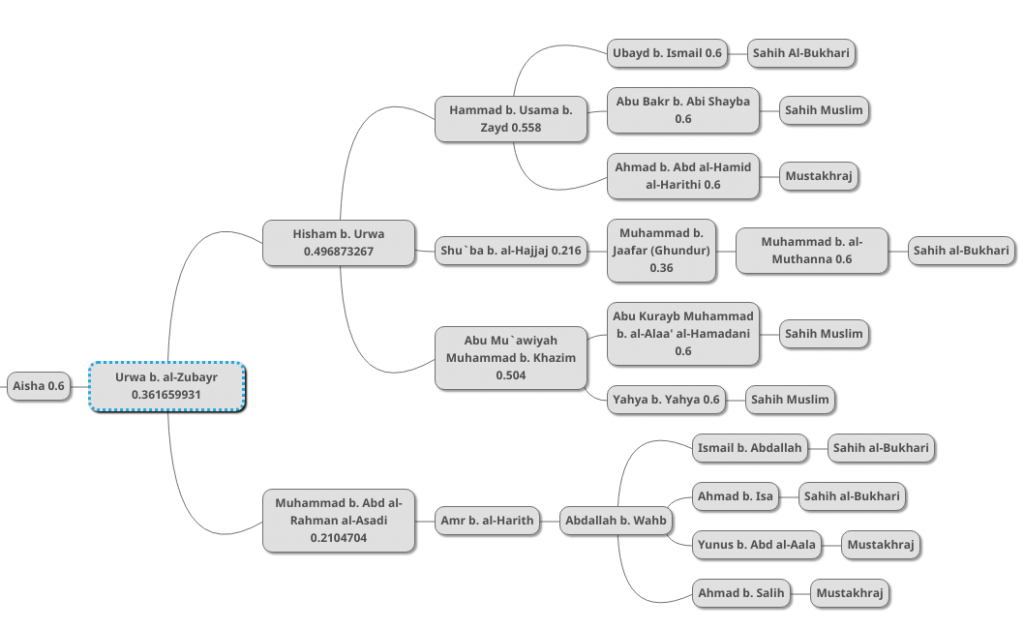

The first step in our hadith scoring is to gather all existing versions of a hadith and their chains and to draw a diagram representing all of their transmitters. Below is a diagram of the version of the “two singing girls” hadiths found in Sahih al-Bukhari:

The blue box is the hadith, and the gray boxes are its transmitters. The first transmitter is Aisha, may God be pleased with her, wife of the Prophet PBUH. The second transmitter is Urwa b. al-Zubayr, her nephew. The third transmitter is Urwa’s son Hisham. The the fourth transmitter is the highly respected hadith scholar Hammad b. Usama b. Zayd. The fifth transmitter is Ubayd b. Ismail, a respected hadith transmitter. This transmitter gave the hadith to Imam al-Bukhari who recorded it.

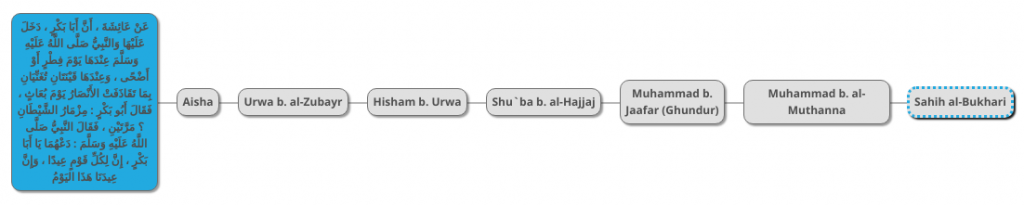

The second version of the hadith is also in Sahih al-Bukhari:

Narrated Aisha:

That once Abu Bakr came to her on the day of `Id-ul-Fitr or `Id ul Adha while the Prophet (ﷺ) was with her and there were two girl singers with her, singing songs of the Ansar about the day of Buath. Abu Bakr said twice. "Musical instrument of Satan!" But the Prophet (ﷺ) said, "Leave them Abu Bakr, for every nation has an `Id (i.e. festival) and this day is our `Id."

Sahih al-Bukhari 3931

Below is a diagram of this hadith’s chain:

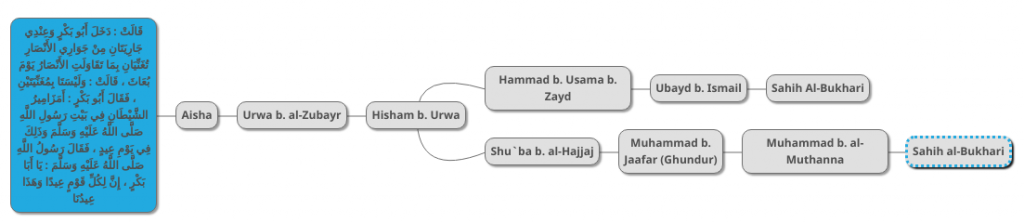

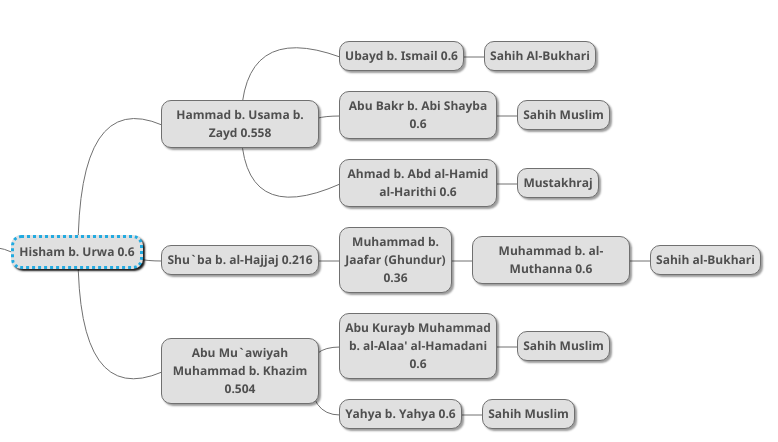

You may note that the first three transmitters are the same as those of the previous hadith. So we can join their diagrams into one as follows:

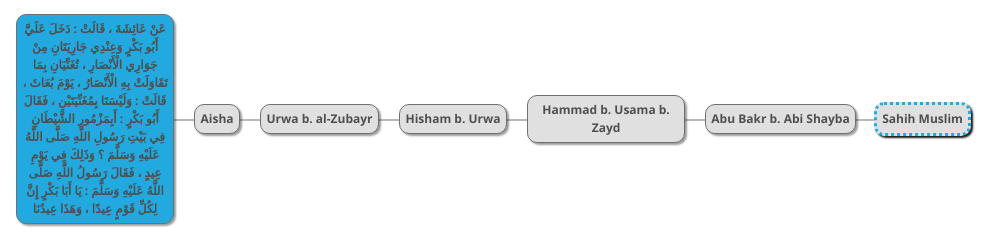

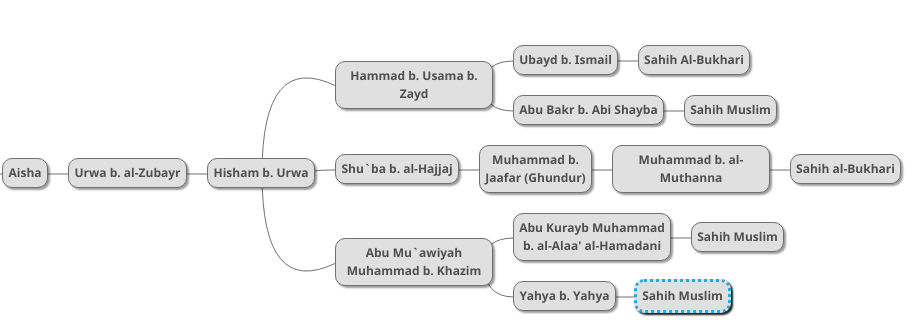

Next is the chain found in Sahih Muslim 892 a:

This chain is exactly the same as the al-Bukhari’s first chain except for the last transmitter. We can therefore join it with the rest as follows:

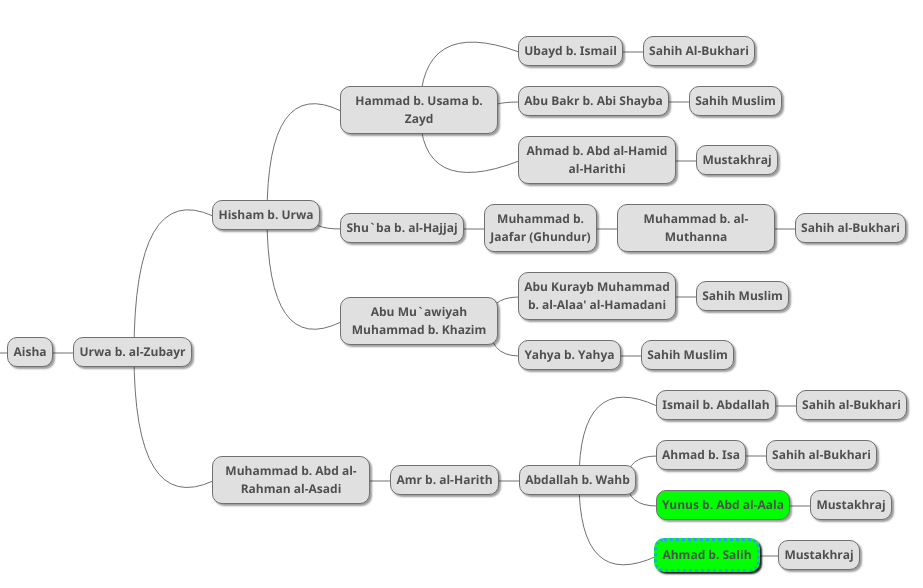

We now therefore have three chains going back to the same hadith. Imam Muslim mentions two additional chains which we add to the diagram as follows:

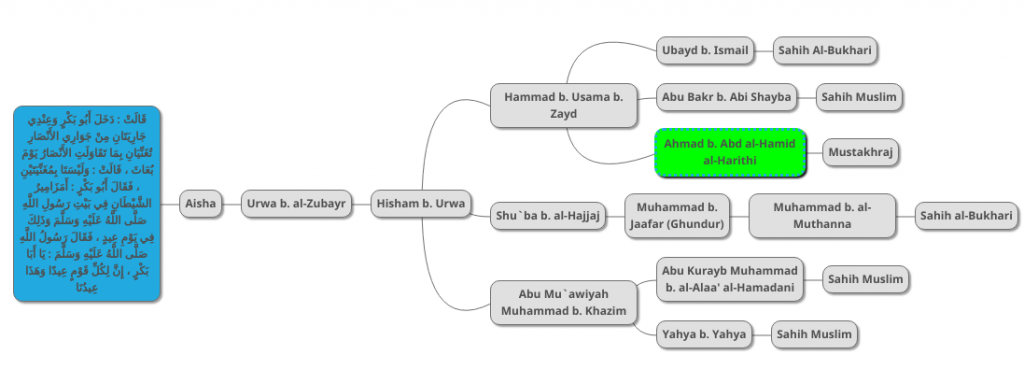

We now move on to other collections that mention the same hadith. The first one is a version mentioned in Abu Uwaana’s Mustakhraj, which we add to the diagram as follows:

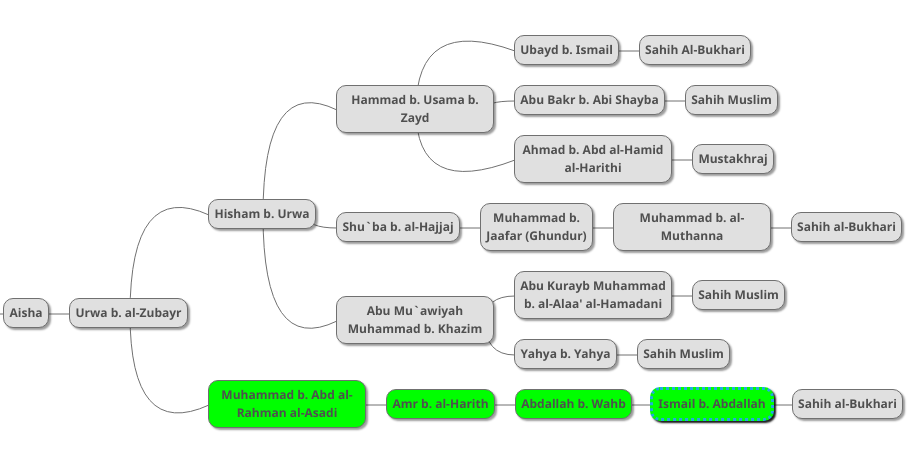

I have indicated the new chain in green. After further research, I was able to discover a further chain in Sahih al-Bukhari as indicated below:

Al-Bukhari mentions an alternative version of this new chain as indicated below:

The scholar Abu Uwana adds two of his own supporting chains to this version as follows:

We now have a fairly complete picture of all of the different chains of this hadith.

The Steps of the HadithRank Algorithm

Our attenuation coefficient of 60% (0r 0.6) indicates that as a hadith passes through more transmitters serially (a->b->c), the likelihood of its integrity goes down. According to the same principle, when a hadith passes through parallel channels (two or more people independently passing the same information on, a->b & a->c), we have a case of diversity gain (or information aggregation, or signal redundancy improving confidence, among many other terms that can be used) that improve the hadith’s strength score; multiple testimonies to the exact same hadith enhance that hadith’s credibility.

To calculate diversity gain, we use standard probability theory procedures by multiplying the likelihood of non-integrity (LNI, the likelihood that the testimony is fabricated/misattributed/corrupt/distorted) of both testimonies, then subtracting the result from a 100% likelihood of integrity (LI):

Person 1's testimony: 60% LI / 40% LNI

Person 2's testimony: 60% LI / 40% LNI

Combined LNI = 40% * 40% = 16%

Combined LI = 100% - 16% = 84%

See the next section below on the explanation for why the calculation is done in this way.

So thanks to having two parallel channels providing the same information, our “signal” jumps from 60% to 84%, meaning that the information we receive is now more credible. In real-world terms, if a person brings us a piece of news and we keep an open mind about whether it is true or false, considering it somewhat more likely to be true than false (α = 0.6), then another person comes and gives us the same news, then our confidence in the news increases according to our estimation of how likely it is that not just one person, but both persons, have brought the exact same false news (very unlikely).

Below, we will take a short detour to explain why we have to multiply probabilities of non-integrity (the chance of the testimony being false or corrupt), as opposed to doing anything more straightforward.

Parallel Transmission (Side-By-Side Witnesses)

The “Both Must Fail” Principle:

When two witnesses independently report the same thing, for the report to be false, both witnesses must be wrong at the same time.

Think of it like two security guards independently watching the same door. For a thief to sneak through undetected, the thief needs both guards to be asleep simultaneously. If Guard 1 sleeps 40% of the time and Guard 2 sleeps 40% of the time (independently), the chance both are asleep at the same moment is 0.4 × 0.4 = 16%. So you have 84% confidence the door is secure.

Similarly, since we assume any randomly chosen transmitter to be wrong 40% of the time, if transmitter 1 is wrong (i.e. provides false information) 40% of the time, and another transmitter 2 is wrong 40% of the time, for their shared testimony on the same hadith to be false requires both to independently get it wrong, which is 0.4 × 0.4 = 16% likely. Therefore, you have 84% confidence in their testimony.

For Chain/Serial Transmission (One Witness to Another)

The “Weakest Link” Principle:

When information passes from Person A -> Person B -> Person C, it’s like a chain. For the message to survive intact, it must pass through every link successfully.

Think of passing a fragile package through several handlers. If Handler 1 has a 60% chance of not breaking it, and Handler 2 has a 60% chance of not breaking it, the package must survive both handlers. The chance it survives both is 0.6 × 0.6 = 36%.

Similarly, if Person A transmits with 60% fidelity and Person B transmits with 60% fidelity, the message must survive both transmissions. Each transmission is an opportunity for corruption, and all must succeed: 0.6 × 0.6 = 36% final fidelity.

The Key Insight: In a chain, every link must hold. Each link is a potential failure point, so reliability decreases.

Intuitive Analogies

Corroboration = Backup Systems: In a given year, your computer has a 1% of dying, causing you to lose all your data lost. If you have two independent computers with the same data, for you to lose your data, both must die simultaneously (1% x 1% = 0.01% chance). Very unlikely!

Chain = Assembly Line: A factory has two stations. Station 1 produces a good part 60% of the time. Station 2 (working on Station 1’s output) produces a good part 60% of the time. For a final product to be good, both stations must succeed: 60% x 60% = 36%.

The Mathematical Logic

Why multiply in both cases?

Because we’re dealing with independent probabilities.

Corroboration / Parallel Transmitters:

- Question: “What’s the chance BOTH are wrong?”

- Answer: (chance first is wrong) x (chance second is wrong)

- Then flip it: 1 – (both wrong) = how likely it is that the testimony is right

Chain of One Transmitter to Another:

- Question: “What’s the chance ALL transmitters got it right?”

- Answer: (chance first succeeds) x (chance second succeeds)

- This directly gives your final confidence

The multiplication happens in both cases—we just multiply different things (failures vs. successes) because we’re asking different questions (both fail vs. all succeed).

Back to the HadithRank algorithm:

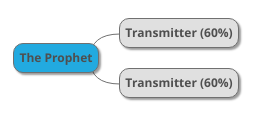

Below is a diagram of an illustrative hadith chain that represents the fact of two transmitters transmitting the same hadith from the Prophet PBUH:

We have testimonies from two people each of whom say that the Prophet PBUH said something. Each of them is given a 60% attenuation coefficient for their testimony, but the strength of the testimonies of the two of them together is 84%, so that the above hadith receives an LI of 84%; this hadith has an 84% likelihood of integrity, of not having undergone fabrication, distortion and other errors.

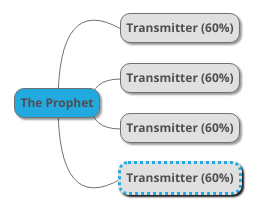

As we add more transmitters, the LI goes up:

Above, we have four supporting witnesses, so the strength of their shared testimonies increases:

NIL: 40% * 40% * 40% * 40% = 2.56%

LI: 100% - 2.56% = 97.44%

In other words, if you have four Companions transmit the same hadith from the Prophet PBUH (and if, in this unrealistic scenario, they were recorded by hadith collectors directly from the Companions), the chance of the hadith being genuine and truly and correctly transmitted is 97.44%, which is a very high chance.

In probability theory texts, “1” represents 100% and “0” represents 0%. So another way of writing down the above calculation, that makes the math easier to use, is as follows:

0.4 * 0.4 * 0.4 * 0.4 (or 0.4^4) = 0.0256

1 - 0.0256 = 0.9744

Back to the hadiths on music, we will first deal with the top part of the diagram, which is as follows:

First, we will fill in the attenuation coefficient by placing 0.6 in each bubble:

We do not add the 0.6 to the bubbles on the far right because those are not transmitters, but recorders (hadith collections), and the various information-theoretic processes that happens during “hops”/transmissions from one individual to another do not apply to them. What concerns us are unwritten, oral transmissions.

Starting from right to left (from the transmitters closest to the hadith collections), the first step is to combine the three middle transmitters’ coefficients vertically, as follows:

NIL: (1-0.6) * (1-0.6) * (1-0.6) = 0.064

LI: 1 - 0.064 = 0.936

Above, each of the three transmitters’ testimonies has a 100% – 60%, or 40% LNI. But in order to get the probability of all of them falsely transmitting the hadith at the same time, we have to multiply these chances together: 40% * 40% * 40% = 6.4%. So the chance of all of them having falsely transmitted the hadith is only 6.4%, meaning that there is a 93.6% chance of them having provided a correct testimony as to the form and contents of the hadith.

We will call this process of combining the strengths of the testimonies of multiple transmitters transmitting a hadith in parallel “parallel combination”. Going by the graph, we vertically combine all of the LIs of the parallel testimonies to get a single number, in this case 93.6%, which represents the combined integrity of all of the testimonies taken together. In this way, the three testimonies are converted into a single stronger testimony, simplifying the mathematical problem.

We next have to do serial combination, when we calculate the decay or reduction in the LI of testimonies, due to their going through multiple hops / transmitters. All three transmitters transmit the hadith from Hammad b. Usama, whose testimony has a 0.6 (60%) LI, therefore we have this case of serial combination:

Hammad b. Usama (60%) -> [the three transmitters combined (93.6%)]

In the case of serial combination, rather than multiplying non-integrity likelihoods, we multiply likelihoods of integrity. The reason is that as information passes down through a chain of transmitters each of whom have a 60% chance of authenticity, the chance of the information being correctly passed down decreases. There is more chance for error and fabrication. If you hear a Companion say that the Prophet PBUH said something, that is far more trustworthy than another person saying they heard their father say that their grandfather said that a Companion said that the Prophet PBUH said such and such. Each additional person in the chain adds more room for the loss of integrity of the message.

We multiply the 0.93 we got earlier by parallel combination by 0.6 to get 0.558, which means 55.8%. As helpful notation, we now update the bubble for Hammad b. Usama to represent this new probability:

Hammad b. Usama’s testimony’s LI went down from 0.6 to 0.558 because we did not hear the hadith directly from him, but from three people who claim to have heard it him. Since those three people’s testimonies have a combined LI of 93% (rather than 100%), this slightly decreases the LI of the information we get from Hammad b. Usama.

We now move on to al-Bukhari’s second chain, which is as follows:

Using serial combination:

0.6 * 0.6 * 0.6 = 0.216

So this second chain has only a 21.6% LI. The reason is that we do not have any supporting transmitters. We only have Muhammad b. al-Muthanna’s word for it that Muhammad b. Jaafar said that, and we only have Muhammad b. Jaafar’s word for it that Shu`ba said that. The deeper a chain goes back in time, the lower its probability of authenticity and accuracy becomes.

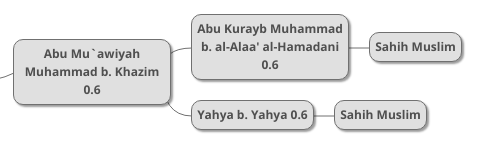

We next deal with two chains from Sahih Muslim:

Starting from the transmitters closest to the hadith collection (we must always start from these, as hadith chains are like branching trees, and we have to close each branch, merging it into one branch, in the correct order, until all of them turn into a single branch, that will get shorter as we go on, until we remain with the hadith all by itself).

Using parallel combination for the middle transmitters, we get an LI of 0.84 or 84%. Multiplying that by 0.6 through serial combination, we get 0.504, meaning that Abu Mu`awiyah’s testimony, as received from the two nearer transmitters, has a 50.4% probability of authenticity.

Next we have the more interesting task of combining all the chains we examined above. We have to perform parallel combination on the probabilities of Hammad (0.558), Shu`ba (0.216) and Abu Mu`awiyah (0.504):

NILs: (1-0.558) * (1-0.216) * (1-0.504) = 0.171877888

LIs: 1 - 0.171877888 = 0.828122112

So the LI of the information coming from these three transmitters and all those who transmitted from them is 82.8%.

Now we serially combine this result with Hisham b. Urwa’s 0.6 probability, resulting in 0.496873267. In this way we have dismissed this entire part of the hadith chain, as if we had received the testimony directly from Hisham b. Urwa.

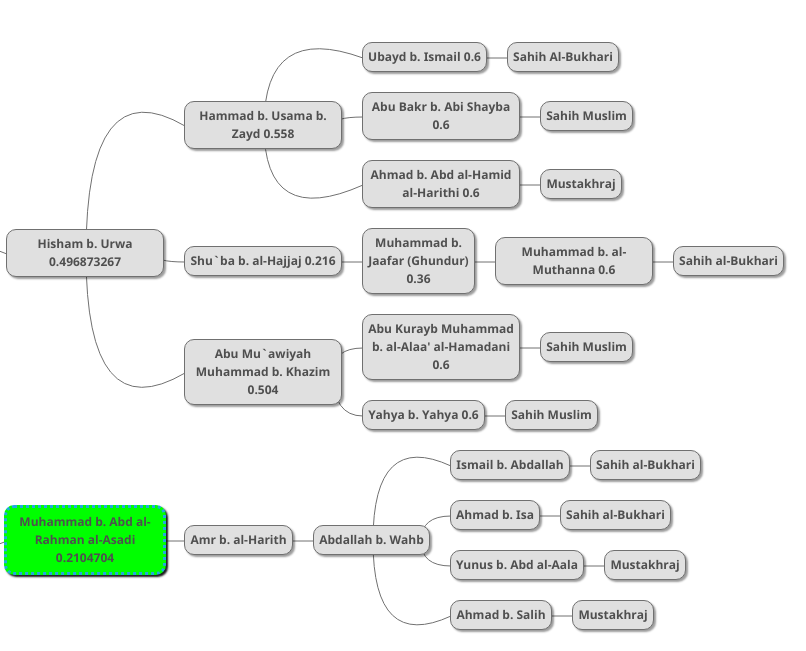

We repeat these same steps for the remaining chains, as follows:

And by vertically combining the left-most probabilities (Hisham b. Urwa’s 49.68% and Muhammad b. Abd al-Rahman’s 21.04%), we get 0.602766552, so the information has a 60.27% probability of authenticity at this stage.

We next multiply this 0.602766552 by Urwa b. al-Zubayr’s 0.6 (serial combination), resulting in 0.361659931.

In the final step, we serially combine this result with Aisha’s 0.6:

The result is 0.216995959. This means that, wrapping all testimonies into a single resulting testimony, this resulting testimony has this LI.

The Hadith That Disapproves of Music

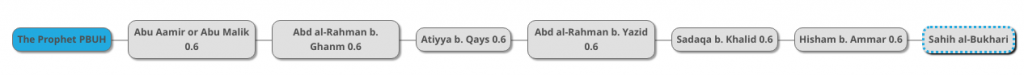

We now move on to Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 5590, the hadith that says misguided Muslims will approve of musical instruments. Below is a diagram of the hadith’s chain:

That’s all. This is a textbook case of a highly questionable hadith. The hadith comes from a single chain that does not branch out, which I call a “precarious” chain. To calculate its score, we merely serially combine all of the 0.6 probabilities as follows (0.6^6):

LI = 0.6 * 0.6 * 0.6 *0.6 *0.6 *0.6 = 0.046656

This hadith therefore has a 4.66% LI, which is extremely low. As discussed in another article, there is another reason to consider this hadith questionable: it says misguided Muslims will consider khazz (a type of clothing) lawful. Imam al-Tirmidhi expresses his incredulity by writing that 20 Companions of the Prophet PBUH wore this type of clothing.

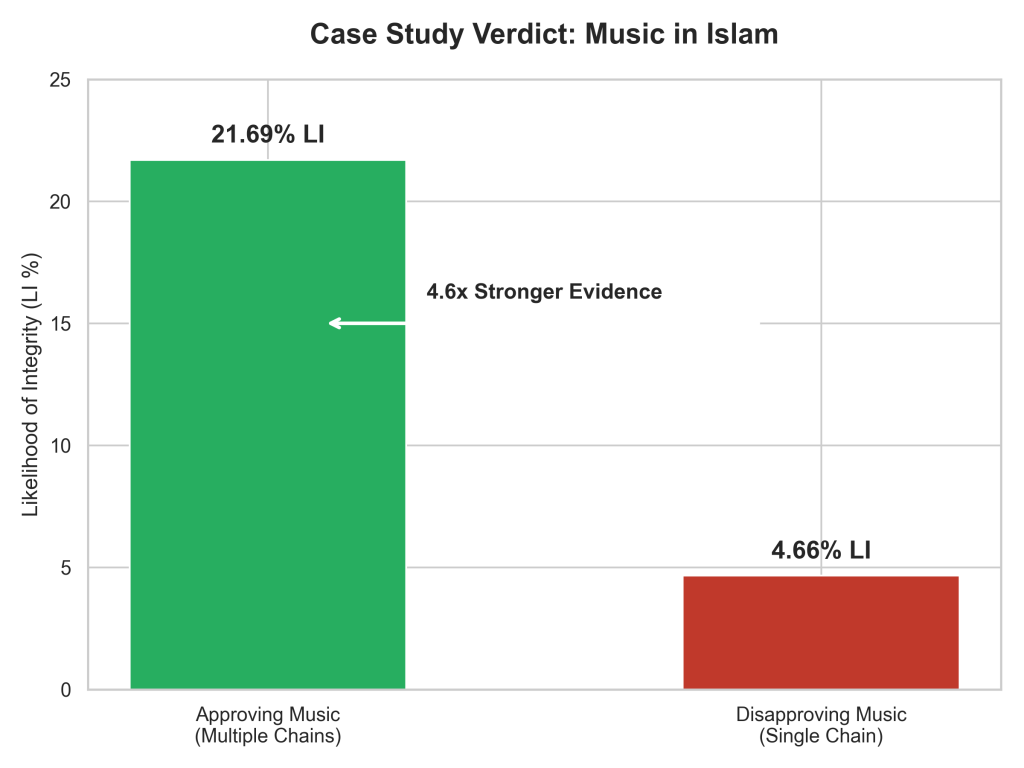

The Verdict

The hadith in which the Prophet PBUH says misguided Muslims will consider musical instruments lawful has only a 4.66% LI, while the hadith in which the Prophet PBUH approves of musical instruments has a 21.69% LI. Thus the hadith in which the Prophet PBUH approves of musical instruments is 4.6 times stronger than the hadith in which he disapproves of them (21.69 ÷ 4.66 = 4.65).

Based on this, we can confidently say that the evidence in support of the lawfulness of musical instruments is far stronger. Therefore, approval of musical instruments is a vastly better representation of the Prophet’s sunna (tradition) than disapproval of them.

On The 60% Attenuation Coefficient

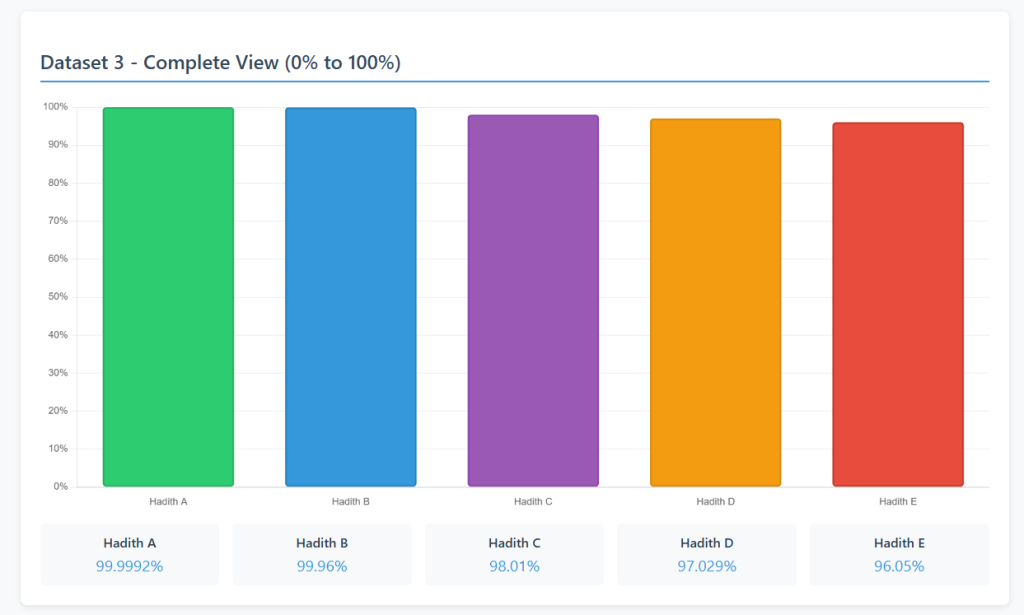

Below is an example that shows 5 hadiths scored based on using an attenuation coefficient of 99% on each testimony instead of 60%.

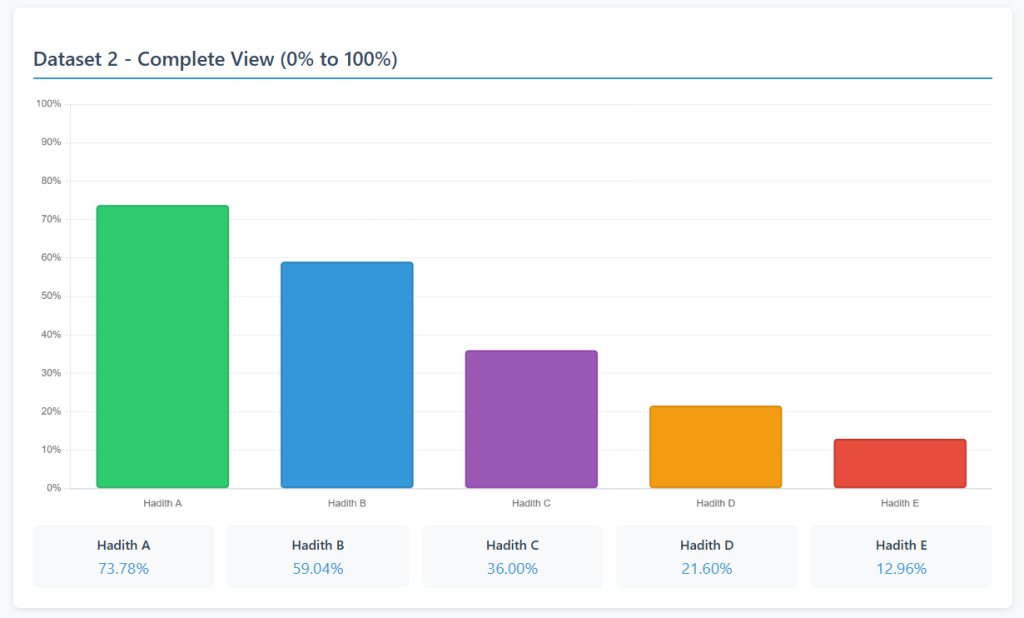

And below are the exact same hadiths scored based on the 60% LI:

With the 99% scoring, our hadiths range from 99.9992% to 96.05% in their LIs. Are these hadiths (hadith A and hadith E, for example) similar in their authenticity or not? By inflating the scores of our transmitters to 99%, we get rather useless numbers when it comes to giving us an intuitive idea of the relative strengths of these hadiths.

In reality, hadith A is a very rare type of extremely high-quality hadith with three isnāds from three Companions, on the following pattern:

The Prophet -> Companion 1 -> ...

-> Companion 2 -> ...

-> Companion 3 -> ...

Hadith E, however, is a relatively low-quality hadith on the following pattern, with only one sanad, received from only 1 Companion, through only 1 transmitter, and through only 1 sub-transmitter:

The Prophet -> Companion 1 -> Transmitter 1 -> Sub-Transmitter 1

The 99% transmitter scoring entirely hides the crucial differences between these two hadiths (hadith A and hadith E), while the 60% scoring gives us the intuitive distinction between 73.78% and 12.96%. This much better aligns with a hadith scholar’s sense of the quality of these two hadiths; the “golden” quality of hadith A and the disappointing quality of hadith E that cries out for supporting isnāds.

In other words, the transmitter score we choose is entirely about utility and convention, our task in choosing a default score is to choose one such that the resulting authenticity scores truly represent the quality of each hadith.

On Mudallis, Non-Hujja, and Other Details of Hadith Transmitters

Above, I have described the general framework of the HadithRank method and its algorithm. There are details I have not spoken of, as they are not part of the essence of the method, but they can make important differences in the results obtained from the method. While I have chosen a 60% factor to “attenuate” individual testimonies, for transmitters who are mudallis, non-qawī, non-ḥujja, or considered weak by some scholars and not others, lower probabilities will have to be used. I have often gone with an attenuation coefficient of 30% for such testimonies where the literature is clearly admitting of both the good and bad qualities of their transmitters.

There are also different levels of weak transmitters. Some are considered weak for ideological reasons (because they held beliefs that hadith scholars considered unacceptable), while others are considered weak because they were caught lying or fabricating hadiths. Different probabilities will have to be used for different levels of weakness.

Conclusion

The HadithRank method can greatly help in resolving issues surrounding contradictory hadith narrations by making it clear which hadiths are superior to which ones. It would be extremely helpful if we could build a new hadith collection that shows the LI of each hadith rather than merely saying whether it is authentic or not.

Further Applications of HadithRank Algorithm

See the articles on the Probabilistic Hadith Verification page for many studies by me in which I use the methodology developed in this article (originally called “the probabilistic method”) to verify hadiths on various important issues.

Appendix: Formal Definition of the HadithRank Algorithm

Formal Definition

Given a rooted tree T where:

- The root represents the original signal with LI = 1.0

- Each internal node n has an associated attenuation coefficient α_n ∈ [0,1]

- Each leaf node is a receiver that records the signal

- Edges represent transmission paths

We define the Likelihood of Integrity (LI) recursively as follows: Base Case (Leaf/Receiver): For a receiver node r:

LI(r) = 1.0

(A receiver doesn’t corrupt; it only records what it receives) Recursive Case (Internal Node with Children): For an internal node n with fidelity α_n and child nodes C = {c₁, c₂, …, c_k}:

- Compute the combined LI of all children:

LI_children = 1 - ∏(1 - LI(c_i)) for all c_i ∈ C

- Multiply by the node’s own fidelity:

LI(n) = α_n × LI_children

System LI: The overall system likelihood of integrity is:

LI(system) = LI(root's child)

(Since the root itself has LI = 1.0 and we begin evaluation at its child)

Key Properties

- Parallel Combination (Siblings): When combining sibling nodes, we use the complement multiplication rule:

This represents: “For all siblings to be corrupt, each must independently be corrupt.”LI_combined = 1 - ∏(1 - LI_i) - Serial Combination (Parent-Child): When a parent transmits to children:

This represents: “The parent’s corruption acts as a bottleneck that limits downstream reliability.”LI_parent = α_parent × LI_children_combined - Bottleneck Property: A node’s unreliability cannot be overcome by downstream branching. If α_n is low, LI(n) ≤ α_n regardless of how many children n has.

JavaScript Implementation of the HadithRank Algorithm

On GitHub: hadithrank

/* HadithRank Algorithm */

/* Copyright (c) 2025 Ikram Hawramani */

/* MIT License with Algorithm Attribution */

class IntegrityCalculator {

constructor(defaultDecay = 0.6) {

this.decay = defaultDecay;

this.tree = { id: 'Source', children: [], isSource: true };

}

/**

* Main entry point: Calculates the final system LI.

* @param {string[]} chains - Array of strings like "Source > A > B (0.3) > C"

* @returns {number} - The final calculated probability (0.0 to 1.0)

*/

calculate(chains) {

this.buildTree(chains);

return this.computeNode(this.tree);

}

/**

* Parses text chains into a hierarchical tree structure.

* Extracts custom fidelity values if present, e.g., "Name (0.8)"

*/

buildTree(chains) {

// Reset tree

this.tree = { id: 'Source', children: [], isSource: true };

for (const chainStr of chains) {

// Split string by ' > ' or any variation of arrows/spaces

const parts = chainStr.split(/\s*>\s*/);

let currentNode = this.tree;

// Start from index 1 because index 0 is always 'Source'

for (let i = 1; i < parts.length; i++) {

const rawPart = parts[i];

// Parse Name and Custom Fidelity

// Matches "Name" or "Name (0.5)"

let nodeName = rawPart.trim();

let customFidelity = null;

// Regex to find parenthetical number at end of string

const match = nodeName.match(/^(.*?)\s*\((\d+(?:\.\d+)?)\)$/);

if (match) {

nodeName = match[1].trim(); // The name "B"

customFidelity = parseFloat(match[2]); // The value 0.3

}

// Find existing child or create new one

let child = currentNode.children.find(c => c.id === nodeName);

if (!child) {

child = {

id: nodeName,

children: [],

isLeaf: (i === parts.length - 1)

};

currentNode.children.push(child);

}

// If this specific chain mention had a custom fidelity, update the node

if (customFidelity !== null) {

child.customFidelity = customFidelity;

}

currentNode = child;

}

}

}

/**

* Recursive calculation engine.

* Logic:

* 1. If Leaf: Return custom fidelity OR default decay.

* 2. If Branch: Combine children (Parallel) -> Attenuate by Node fidelity (Serial).

*/

computeNode(node) {

// Determine this node's specific attenuation factor

// Use custom fidelity if set, otherwise use global default

// And use global default if custom fidelity is higher than the default,

// as this implies a fundamental misunderstanding of the algorithm

// (the default should represent a "law of nature" that cannot be

// sidestepped)

const nodeFidelity = (node.customFidelity !== undefined && node.customFidelity <= this.decay)

? node.customFidelity

: this.decay;

// BASE CASE: Leaf Node (Witness)

// Represents the hop from the Implicit Receiver -> Witness

if (!node.children || node.children.length === 0) {

return nodeFidelity;

}

// RECURSIVE STEP 1: Calculate all children first

const childValues = node.children.map(child => this.computeNode(child));

// RECURSIVE STEP 2: Parallel Combination (Noisy-OR)

// Formula: 1 - product(1 - childValue)

let inverseProduct = 1.0;

for (const val of childValues) {

inverseProduct *= (1.0 - val);

}

const combinedLI = 1.0 - inverseProduct;

// RECURSIVE STEP 3: Serial Attenuation (The Bottleneck)

// The Source (Root) is Truth (1.0) and does not attenuate.

// All other nodes multiply the incoming combined signal by their fidelity.

if (node.isSource) {

return combinedLI;

} else {

return combinedLI * nodeFidelity;

}

}

}

// Export

if (typeof module !== 'undefined' && module.exports) {

module.exports = IntegrityCalculator;

}

const calculator = new IntegrityCalculator();

const hadithChains = [

'Source > A > B > C',

'Source > A > B > D',

'Source > A > E > F',

'Source > G > H > I > J',

'Source > G > H > I > K',

'Source > G > H > I > L'

];

const result = calculator.calculate(hadithChains);

console.log(`Final Integrity Score: ${(result * 100).toFixed(4)}%`);

// Output should be roughly: 52.89%

const calculator2 = new IntegrityCalculator();

const hadithChains2 = ['Prophet Muhammad PBUH > Companion 1 > Transmitter A > Transmitter B > Transmitter C',

'Prophet Muhammad PBUH > Companion 1 > Transmitter A > Transmitter B > Transmitter D',

'Prophet Muhammad PBUH > Companion 1 > Transmitter A > Transmitter B > Transmitter E',

'Prophet Muhammad PBUH > Companion 2 > Transmitter F > Transmitter G',

'Prophet Muhammad PBUH > Companion 2 > Transmitter H > Transmitter I > Transmitter J > Transmitter K'];

const result2 = calculator2.calculate(hadithChains2);

console.log(`Final Integrity Score: ${(result2 * 100).toFixed(4)}%`);

// Output should be roughly: 41.42%

const calculator3 = new IntegrityCalculator();

/*

The values for less-reliable-than-default transmitters should ideally follow

standardized criteria, and they could also be based on:

1. Additional data provided by other empirical analyses of hadiths and their transmitters.

2. Probabilistic criteria derived from the jarh literature: get the transmitter's reliability based on what the top scholars say about them (the exact words a scholar uses may serve as important indicators of the scholars' attitude towards the transmitter), a kind of averaging of their opinions, perhaps with some scholars given more weight.

*/

const hadithChains3 = ['Prophet Muhammad ﷺ > Reliable A > Lower-Quality Reliable Transmitter B (0.45) > Reliable C',

'Prophet Muhammad ﷺ > Reliable D > Half-Reliable Transmitter E (0.3) > Reliable F',

'Prophet Muhammad ﷺ > Reliable D > Questionable But Not Daif Transmitter G (0.2) > Reliable H'];

const result3 = calculator3.calculate(hadithChains3);

console.log(`Final Integrity Score: ${(result3 * 100).toFixed(4)}%`);

// Output should be roughly: 30.198%