Recently I have been reading many works on Islamic theology (kalām) in order to find answers to certain questions and paradoxes inherent within the Islamic theological worldview.

Since I was already familiar with Ashʿarite theology (Islam’s dominant theological school), I decided to focus on al-Māturīdī (d. 944 CE), who represents Islam’s alternative yet orthodox theological school popular in the Ḥanafī school and propagated by the Seljuqs and Ottomans. The Māturīdite school is thought to be more reasonable and balanced than the Ashʿarite school, although they agree on many important questions. In the admirably detailed and precise study al-Māturīdī and the Development of Sunnī Theology in Samarqand (published in German in the 1990’s and in English in 2014) the German scholar Ulrich Rudolph presents what we know about al-Māturīdī’s life (we know very little actually) and the development of his thought.

Al-Māturīdī was the first Ḥanafite scholar to truly develop a theological system that could compete with the Muʿtazilites yet maintain respect for traditional views starting with Abū Ḥanīfa’s (d. 767 CE). He was extremely well-versed in Muʿtazilī theology and even had some knowledge of philosophy.

After finishing that book, I went on to read Bulqāsim al-Ghāli’s 1989 study Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī and His Theological Views (Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī wa-Āraʾuhu al-ʿAqdīya). The book was largely lacking in details and I did not learn too much that is new from it. I then read the 2009 book Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī and His Kalām Opinions (Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī wa-Āraʾuhu al-Kalāmīya) by ʿAlī ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Maghribī. This book is based on a PhD dissertation. This book may be the first Arabic book that discusses al-Māturīdī’s theology at a very high scholarly standard and makes full use of al-Māturīdī’s neglected commentary on the Quran.

One of al-Māturīdī’s great contributions to Islamic thought is his defense of free will without submitting to the Muʿtazilite framework. Other members of the Maturidite school, such as al-Taftazānī (d. 1389 CE) and Qadi Zadeh (d. c. 1600 CE) continued the tradition of affirming the existence of true free will in humans. Their position is therefore opposed to the position of important Ashʿarite theologians like al-Rāzī who believed humans only appear to be free but are in reality completely lacking in freedom.

I next read Frank Griffel’s Al-Ghazālīʾs Philosophical Theology, one of the best studies of al-Ghazālī up to date. He refutes the tired old trope that al-Ghazālī “destroyed” Islamic philosophy and shows that he was actually essential to the integration of Aristotelian-Avicennan philosophy within Islamic theology.

The scholar Richard M. Frank had accused al-Ghazālī of secretly being a follower of Avicenna and only paying lip service to his own Ashʿarite school. One of Griffel’s tasks in this book is to refute that view and show that al-Ghazālī continued to adhere to orthodox Islamic theology while also embracing significant Avicennan influences.

In their determination to uphold God’s absolute power and control over the universe, Ashʿarite theologians argued that God is the only “actor” in the world. Humans have no power to move anything in this world unless God moves it for them. They also developed the theory of “atomistic time” that says that nothing has the power to exist from one moment to another by itself. It is God who re-creates every object and its properties moment by moment. When a ball rolls, it is not that its atoms move. It is actually God who this moment allows the atoms to be at this position, and the next moment He re-creates the atoms at the next position, and so on during each moment. This is similar to the way that in a video game when something moves, the computer simply changes the information held inside the computer hardware in order to create the impression of movement. The universe, in the Ashʿarite and Māturīdite worldviews, which is known as occasionalism, is like a computer simulation controlled by God. Nothing has any objective reality of its own, and nothing has the power to cause anything. Reality is entirely a “computer simulation”, like in the film The Matrix, that God controls and operates.

Besides solving the problem of how God relates to the universe and how human actions come about, this worldview also solves the problem of miracles. The laws of nature are merely God’s habits in the way He operates the universe. He has the power to suspend these habits in certain circumstances and bring about miracles since He is not chained by the laws of nature. The laws of nature are simply the rules of the simulation that God Himself maintains. He can operate it according to different rules if and when He chooses. He can cause a mountain to fly because there is no outside rule that prevents this. The laws of nature are properties of things inside the simulation. But since God is outside the simulation, He can do anything He wants regardless of nature.

This might be one of the magnificent achievements of Islamic thought. Muslim theologians were able to think outside the box of the universe and freed their conception of God from the chains of nature. In this way they were able to reaffirm God’s absolute power and transcendence more explicitly and powerfully than had ever been done before as far as I am aware.

Some have objected that viewing the world in the occasionalist way makes science impossible since it teaches that causes do not necessarily lead to effects. Al-Ghazālī mentioned the famous example that a piece of cotton will not necessarily burn when it touches fire–it only burns because God makes it burn. Ibn Rushd (Averroes) criticized this by saying this makes the world arbitrary and makes real knowledge impossible, since we can never be sure if what we consider the laws of nature this moment will continue to be the laws of nature the next moment. Robert R. Reilly, in his book The Closing of the Muslim Mind (which I reviewed and refuted here) accepts Ibn Rushd’s criticism and thinks that al-Ghazālī is promoting a senseless and irrationalist worldview. But al-Ghazālī himself mentions and replies to this criticism in his Incoherence of the Philosophers. It is God who operates the universe, but He operates it in a predictable and rational manner. So saying that everything happens because of God does not prevent us from having a scientific worldview. Science merely studies God’s habits. The laws of nature are stable and we can expect them to continue being stable. We just admit that the laws are upheld by God and that there is no power forcing God to operate them a certain way. He just decided to operate things in this way.

So as a lover of science I can be perfectly happy with occasionalism, viewing the universe as a simulation controlled and operated by God, while also appreciating and contributing to science. Science is merely the study of God’s habits and handiwork in the universe. I am as much a rationalist and skeptic as any scientist, but I believe that God runs the show behind the scenes. My view that God is in charge behind the scenes has no influence on my scientific worldview. I am exactly like a scientist who believes the universe could be a simulation–there are in fact scientists who admit this possibility. Occasionalism, therefore, is not irrationalism. It is simply to admit this possibility of the universe being a simulation, a possibility that even atheists can admit. The disagreement then would be about whether the simulation is controlled by God or some other entity.

We further strengthen occasionalism’s rationality by proposing what I call a principle of “plausible deniability”. It is God’s will that He should remain hidden and that His existence should be scientifically unprovable. His existence should be deniable–humans should be able to disbelieve in Him. This allows humans to choose whether to be believers or not. God does not want to force belief on people as the Quran makes clear. Therefore the principle of plausible deniability says that the universe must act in a scientific way to preserve God’s hidden-ness. There should never be any “glitches in the Matrix” that cause scientists to doubt the universe really works scientifically (i.e. miracles should not happen on an everyday basis, making it impossible to reach scientific conclusions about how the world works). As an occasionalist who believes in the principle of plausible deniability, I fully believe in an utterly rational and scientific universe.

Richard M. Frank argued that al-Ghazālī is a non-occasionalist who believes in secondary causes (meaning that he does not really believe the universe is like a simulation controlled by God, rather, he believes that it operates according to pre-determined “natural laws” as Avicenna believed). Michael Marmura disagreed and argued for the exact opposite; al-Ghazālī was a complete occasionalist who only mentioned Avicennan causality as mental experiments meant for argumentation with the philosophers. Griffel disagrees with both of them and offers what he considers to be a synthesis: al-Ghazālī was undecided as to whether the universal really runs in an occasionalist way or whether it runs in an Avicennan way. As he himself says in the Incoherence, both options are equally acceptable to him.

Al-Ghazālī says that we can either explain miracles the occasionalist way, by saying that God temporarily changed the laws of nature, or the Avicennan way, by saying that miracles are natural events whose causes we simply do not know. The stick of Moses that turned into a snake may have actually followed a sped-up version of natural causation. Perhaps the stick decayed extremely quickly and a snake was caused to come alive from the same material according to natural laws (I prefer the first, occasionalist, explanation).

Al-Ghazālīʾs teacher al-Juwaynī (d. 1085 CE) followed the classical, “occasionalist” Ashʿarite conception that God creates every human action. He also seems to have been influenced by philosophical ideas about “secondary causality”, believing that human actions were largely (or entirely) the result of previous causes that create in them the motivation to do certain things.

Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 1210 CE) subscribed to a similar theory, believing that previous circumstances determine what humans do. Unlike previous thinkers, he correctly recognized that if all human actions are predetermined by God and come from previous causes (themselves also predetermined by God), then there is no room for human free will. He therefore concluded that humans only appear to be free-willed. They do not really have free will. I would have expected someone as intelligent as al-Rāzī to have come up with a better solution, so it is disappointing that he was satisfied with this intellectual dead-end.

So according to al-Juwaynī, al-Rāzī and also al-Ghazālī, since God has foreknowledge of everything, it is as if He already has a “film” of how history will play out. Everything we say and do is already in the film. Yet we are still somehow responsible for our actions. Recognizing the dangers this realization poses to Islamic belief, al-Ghazālī says:

Accept God’s actions and stay calm! And when the predestination is mentioned, be quiet! The walls have ears and people who have a weak understanding surround you. Walk along the path of the weakest among you. And do not take away the veil from the sun in front of bats because that would be the cause of their ruin.

So that appears to be the state of affairs in orthodox Islamic theology when it comes to the conflict between free will and predestination. We are responsible for our actions–yet everything we do is already written and recorded. And since this would upset people if they heard it, the recommendation is to just not talk about it.

This rather dreary view of the universe did not get significantly challenged within mainstream Sunnism until Ibn Taymiyya came along.

Ibn Taymiyya’s Theology

Jon Hoover’s essay in Ibn Taymiyya and His Times (which I reviewed here) had informed me that Ibn Taymiyya has unique solutions that could help end the intellectual dead-end that orthodox Islamic theology had arrived at with thinkers like al-Ghazāli and al-Rāzī. I therefore decided to read Hoover’s Ibn Taymiyya’s Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism, a highly detailed and informative study of Ibn Taymiyya’s theological thought that is based on Hoover’s doctoral dissertation,

The Ashʿarites denied that God created the universe for a purpose, because in their view this implies that God has a need for the universe, which implies that God is imperfect. In order to defend God’s absolute needlessness, they had to assert that the creation of the universe was totally without desire, aim or purpose.

The Ashʿarites also came up with the idea of dead-time (already mentioned) where all of history, past, present and future is like a film that God already possesses. They had to assert this because they thought that assuming the future to be non-existent would imply that God’s knowledge changes (increases or decreases) as time moves forward. To them change in God was unacceptable because it implied imperfection. God should already know everything that my possibly happen from pre-eternity so that His knowledge may stay still and never change.

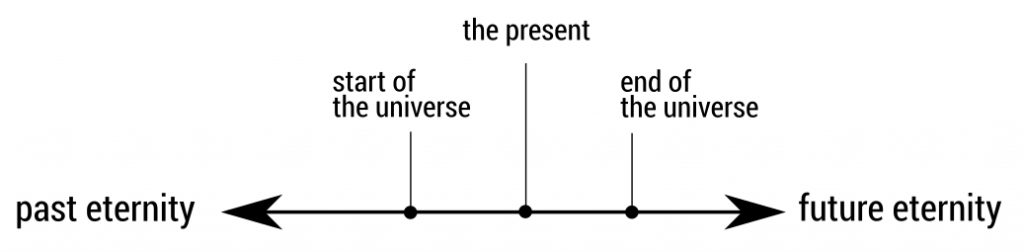

Ibn Taymiyya rejected that view of time. To him God exists in “real time”. If you envision eternity as a line, the present moment is a point on it and we and God experience it together. Even though God is eternal and the universe was created in time, this does not mean that God’s time is dissociated from the universe’s time. Time is real everywhere. Below is a diagram of how Ibn Taymiyya may have understood time:

According to Ibn Taymiyya, if God had already willed everything that may happen from pre-eternity, that means nothing would ever happen because everything would already be complete, like a finished film on a shelf. But the reality is that we experience time and change, which to him proves that time is real and that God’s will interacts with the universe in real time rather than having interacted with it just once in pre-eternity as the Ashʿarites claim.

The Ashʿarites had to posit a changeless knowledge and will in God to defend the Greek-inspired idea that God does not change. Ibn Taymiyya criticizes this idea of a chained God who cannot will or create anything truly new. He says a God who can will and create new things in time is actually more perfect than one who cannot do that. In this way, he defends the real-time view of God against the dead-time of the Ashʿarites. To Ibn Taymiyya, God is perpetually dynamic, active and creative in real time, since such a God is more perfect than a still God.

A person may object that this means God is subject to time. In reality time is subject to God–God creates time moment by moment by His will and power. God is eternal, but one of His actions can precede another (since we say a dynamic God is more perfect than a still God), and “time” simply means the succession of God’s acts. If God stopped acting, time would stand still–the universe would be like a paused video game. God acts every moment by causing atoms and photos to vibrate and move, and this is perhaps what causes time to exist. If everything stopped moving, time would stand still.

And they ask you to hasten the punishment. But God never breaks His promise. A day with your Lord is like a thousand years of your count.

The Quran, verse 22:47

The above verse both suggests that God is involved dynamically with time, and that time is relative. God can control how fast time moves in a universe merely by slowing down or speeding up how fast photons and atoms vibrate and move. The above verse suggests that our universe runs very fast compared to how God measures time on the outside of the universe. 1000 years pass here inside the universe when only one day passes with God. It is as if we live in a video game that has been sped-up by a factor of about 354360 (these are the number of days in 1000 lunar years).

Ashʿarites say it is impossible for God to do things one after another since He should do everything in one instant in pre-eternity. But Ibn Taymiyya says that a God who creates things one after another is more perfect. And if God creates things one after another, and if He creates each moment, then this means time is real, for us and for God, by God’s own choice in choosing to create each moment. Ashʿarites say time is just an illusion and this makes them deny free will since they think God should already have a film of all of history. But if time is real, if God is creating each moment the very moment it happens, this makes room for development and change in the film of history. History would not be a closed book or completed film, but a living and developing story.

Both the Ashʿarites and Muʿtazilites said that God is aimless and purposeless in creating the universe, since otherwise it would mean that God gained something from creating the universe. It would mean that God was imperfect and aimed to become perfect by creating the universe. But Ibn Taymiyya responds:

Anyone who commits an act in which there is neither pleasure, nor benefit nor profit for himself in any respect, neither sooner nor later, is aimless, and he is not praised for this.

Ibn Taymiyya says that a God who acts with wise purpose is more perfect than a purposeless God, so God must have a wise purpose in creating the universe. Ashʿarites respond that this implies God was imperfect and had a need in order to perfect Himself. Ibn Taymiyya responds that perfection means doing everything in its own time and imperfection is when something is absent when it should be present. Thus to Ibn Taymiyya perpetual, dynamic and wise creation is an expression of God’s perfection. It is not purposeless because to create with purpose is an attribute of God from eternity and an expression of His perfection. He has no need for the creation, but it is an expression of His perfection to create perpetually.

Ibn Taymiyya’s theology falls short of resolving the predestination and free will paradox. He says that God is the one who creates all human acts (something we can agree with), but he goes on to say that God also creates the causes that lead to humans choosing one thing over another. While he argues extensively that humans are responsible for their actions, he also argues for the contradictory position that humans ultimately have no choice, saying human choice actually is jabr bi-tawaṣṣut al-irāda (compulsion by means of the will [that God Himself creates]), which is also what al-Rāzī says.

Defending Free Will with the Maturīdīs

While Ibn Taymiyya failed to resolve the predestination and free will paradox, he provided an important building block for the solution, namely refuting the Ashʿarite view of “dead time”, replacing it with the theory of real time–the idea that God’s acts follow each other, therefore time is real and history is not a finished film; it is a developing story. The future is non- existent and God brings about each new moment of history in real time. When He answers a prayer, He really and truly intervenes in the universe to bring about a change for the benefit of the person, while the Ashʿarites say the prayer and its answer both would have already been written and compelled from pre-eternity.

Ibn Taymiyya’s theology often depends on the consideration of what is the most perfect quality for God to possess. He thus says an active and dynamic God is more perfect the Ashʿarite still God. The question to ask is this: what God is more perfect, one who can create a truly free-willed creature, or one who cannot make such a creature?

Ashʿarites, al-Ghazāli, al-Rāzī and Ibn Taymiyya all say that God is utterly chained by His very nature into being incapable of creating free-willed creatures since He must create all intentions, wills and actions. God is incapable of making room for humans to be free.

Is that God more perfect or a God who has the power to create creatures who are truly free? We humans can make robots, but we can never give them the power to have free will. Everything they do will always come from their programming. Even if we allow them to freely choose what to do based on their environment, it is the environment that decides completely what they should do. Even if we add a bit of randomness to their decisions so that they randomly choose between their choices, there will be no wisdom or choice in their decision. It will be random, arbitrary, purposeless.

What is unique about humans is that unlike robots, they have an extra dimension to them that gives them the ability to truly choose, as the Maturīdī scholars believe. This is likely the Trust that God refers to in this verse:

We offered the Trust to the heavens, and the earth, and the mountains; but they refused to bear it, and were apprehensive of it; but the human being accepted it. He was unfair and ignorant.

The Quran, verse 33:72

God has entrusted us with a power that He Himself, in His wisdom and creativity, created–the power of a creature to choose between good and evil. We can therefore say with al-Māturīdī that there is an element of ikhtiyār (the ability to choose) given to humans by God.

We do not say, like the Muʿtazilites and Qadarites, that humans create their own actions. We instead can propose the following three-step process:

- The human intends based on a power delegated to them by God. Humans are given the power by God to create their own intentions. A God who can delegate decisions to His creatures is more perfect than a God who is incapable of delegation.

- God either creates a will in them (or does not create it)

- God either creates the external action (or does not create it)

God is therefore utterly in charge of the universe and humans can never will anything unless God wills it and permits it (in the second step). We humans can only intend things, based on the ikhtiyār (freedom to choose) that God has given us, and it is God who creates everything else from then on.

We can also reject the Muʿtazilite/Qadarite view that God does not create evil actions. They say if God created evil actions He would be responsible for them. But we say that when humans intend evil, God, when He wishes, may allow it to happen out of a wise purpose that He has. God is not responsible for evil because evil comes from human intentions. He only carries out those intentions in order to preserve the system of the universe that He has created. When the human intends evil, God may treat them with khidhlān (forsaking) as Abū Ḥanīfa and al-Māturīdī say, allowing the evil to be carried out. I discuss the problem of evil and its solution in more detail in my essay: Why God Allows Evil to Exist, and Why Bad Things Happen to Good People.

Predetermination (Qadar) in the Quran

There are authentic narrations where the Prophet PBUH suggests humans have no free will. The issue of hadith will be dealt with later. The Quran itself, however, never tells us anywhere that future human decisions are already written and known beforehand. The predetermination that the Quran talks about is always about things that befall humans from the outside:

But God will not delay a soul when its time has come. God is Informed of what you do. (63:11)

God created you from dust, then from a small drop; then He made you pairs. No female conceives, or delivers, except with His knowledge. No living thing advances in years, or its life is shortened, except it be in a Record. That is surely easy for God. (35:11)

Whatever good happens to you is from God, and whatever bad happens to you is from your own self. We sent you to humanity as a messenger, and God is Witness enough. (4:79)

No calamity occurs on earth, or in your souls, but it is in a Book, even before We make it happen. That is easy for God. (57:23)

The Quran also tells us that guidance comes only from God:

O you who believe! Do not follow Satan’s footsteps. Whoever follows Satan’s footsteps—he advocates obscenity and immorality. Were it not for God’s grace towards you, and His mercy, not one of you would have been pure, ever. But God purifies whomever He wills. God is All-Hearing, All-Knowing. (24:21)

You cannot guide whom you love, but God guides whom He wills, and He knows best those who are guided. (28:56)

If we base our opinions only on the Quran and a number of authentic hadiths, the view of predestination that we get is that God is in charge of all external circumstances of humans. He is also in charge of guiding us. We, however, are in charge of choosing our internal responses. God can give us guidance but we can intend rejection of it. This is what kufr means, to know the truth about God, to be guided to God, but to deny Him anyway.

Rather than telling us that the world is like a film that is already finished, the Quran gives us the impression that the universe operates in real time as Ibn Taymiyya says. What is “written” in our predestination are the external circumstances in our lives. God knows exactly whether we will get that job and when we will be living next year and when we will die. The external circumstances of our lives are entirely in His charge. But this does not mean that our circumstances are rigid and unchangeable. The Quran says:

God erases whatever He wills, and He affirms. With Him is the Mother Book. (13:39)

This gives the impression that the Protected Tablet (al-Lawḥ al-Maḥfūẓ) is not rigid but changeable. The Prophet PBUH supports this view in this sound narration:

لَا يَرُدُّ القَضَاءَ إلَّا الدُّعَاءُ، وَلَا يَزِيدُ فِي العُمُرِ إلَّا البِرُّ

Nothing counters God's decree except supplication, and nothing increases lifespan except righteousness.

(Narrated in al-Tirmidhi, authenticated by al-Albani in al-Silsila al-Sahiha 154 and in Sahih al-Jami` 7687)

According to the above hadith, if your present choices have made you deserve Hell, all that you need to do is pray for guidance and forgiveness, and that will change God’s decree. The Prophet PBUH also prayed for God’s decrees to be changed:

... and I ask you to make every decree You decree for me to be a good.

Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān 870; Muṣannaf Abī Shayba 28767

and also:

O Allah, whoever believes in you, and bears witness that I am your messenger, then cause him to love meeting you, and ease your decrees on him, and decrease from him the worldly life. And whoever does not believe in you, and does not bear witness that I am your Messenger, then do not cause him to love meeting you, and do not ease your decree on him, and increase for him of the worldly life.

Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān 208

and also:

Narrated Anas:

Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) said," None of you should long for death because of a calamity that had befallen him, and if he cannot, but long for death, then he should say, 'O Allah! Let me live as long as life is better for me, and take my life if death is better for me.' "

Ṣaḥīh al-Bukhārī 6351

The above prayers only make sense if the future, i.e. qadar, was changeable.

When the Prophet PBUH says that our place in Paradise or Hell is already determined, we can interpret this as saying that if the world ended today, God knows whether we will be in Paradise or Hell. But this does not mean that we cannot change our place through prayer.

God’s qadar (predetermination) may simply refer to the fact that all alternative futures that God offers us are controlled by Him. You can choose to be good or bad, but in both alternative futures you may predestined to become a doctor. Even though we choose between futures, God creates the shape and nature of all futures.

Ibn Taymiyya’s real-time view of the universe and the Māturīdī affirmation of true free will help create a coherent theory of free will in Islam.

The Ashʿarite views of dead time and a still God contradict free will, since in their view nothing new ever happens. Everything is already finished, so we only appear to be living, breathing and choosing. But Ibn Taymiyya’s real-time view tells us that the future is non-existent and God actively and creatively creates it moment by moment. Accordingly, there is room for free will since we interact with God in real time. God’s predetermination simply means that He decides the shape of all alternative futures. But He does not force us to choose one future and avoid another. He gives us a true free choice in deciding which future we want to be in.

The views offered here are perfectly in concordance with everything the Quran says. As al-Rāzī admits, the verses on predestination and free will can be used to argue both for hard determinism and for free will. He and others like Frank Griffel think that the Quran has a contradictory stance toward predestination and free will; God determines everything, yet humans are responsible for their actions.

But by merging Ibn Taymiyya and the Māturīdī school’s views, we can resolve all apparent contradictions: God determines and creates all futures, but humans decide which futures they will be in. We can never escape what God has determined, but at times God offers us alternative futures and we choose which one we will be in. Our choice of which future we will be in is never said to be predetermined in the Quran. It rather constantly affirms the alternative, that it is we who decide whether we corrupt or purify ourselves with our choices.

And [by] the soul and He who proportioned it.

And inspired it with its wickedness and its righteousness.

Successful is he who purifies it.

Failing is he who corrupts it.

The Quran, verses 91:7-10.

And if we make good choices, God decrees further good things to happen to us:

And when he reached his maturity, and became established, We gave him wisdom and knowledge. Thus do We reward the virtuous.

The Quran, verse 28:14

Moses [as] was virtuous, so God decreed that He should gain wisdom and knowledge.

Whoever works righteousness, whether male or female, while being a believer, We will grant him a good life—and We will reward them according to the best of what they used to do.

The Quran, verse 16:97

Above, God affirms that He will decree a good worldly life for those who work righteousness.

And when your Lord proclaimed: “If you give thanks, I will grant you increase; but if you are ungrateful, My punishment is severe.”

The Quran, verse 14:7

Above, God affirms that there is a contractual relationship between the believers and Himself. If we are grateful, He will decree for us an increase in good things. And if we are ungrateful, He will cause us torment.

Life is like walking down a road created by God. At some points the road forks into multiple roads (also all created by God), but we are free which of these roads we choose to walk down. God responds to righteous choices by decreeing good things for us, and responds to wicked choices by decreeing hardships and disasters for us.

In Sheba’s homeland there used to be a wonder: two gardens, on the right, and on the left. “Eat of your Lord’s provision, and give thanks to Him.” A good land, and a forgiving Lord.

But they turned away, so We unleashed against them the flood of the dam; and We substituted their two gardens with two gardens of bitter fruits, thorny shrubs, and meager harvest.

We thus penalized them for their ingratitude. Would We penalize any but the ungrateful?

The Quran, verses 34:15-17

One of the biggest problems in the Quran regarding free will and predestination are in verses 4:78-79, which some believe are contradictory:

Wherever you may be, death will catch up with you, even if you were in fortified towers. When a good fortune comes their way, they say, “This is from God.” But when a misfortune befalls them, they say, “This is from you.” Say, “All is from God.” So what is the matter with these people, that they hardly understand a thing?

Whatever good happens to you is from God, and whatever bad happens to you is from your own self. We sent you to humanity as a messenger, and God is Witness enough.

The Quran, verses 4:78-79

But according to my Taymiyyan-Maturīdī synthesis, the first verse is saying that whatever befalls humans does so because God caused it (moved the relevant atoms, etc.) for the thing to happen. So it is all from God. It also means that God is utterly in charge of all futures, so whatever future comes about, it is always from God. The second verse, however, says that the reason why a thing befalls you could either be God’s favor upon you (if it is a good thing) or the result of your own bad choices (if it is a bad thing).

In other words, when faced with two futures, future A (good) and future B (bad), both are created by God. But if you choose the good future and it takes place, that is a blessing from God. And if you choose the bad future, that is your own fault. So both futures are from God, and the bad future takes place because of your choice.

This may be why the Prophet says:

لَا يَقْضِي اللَّهُ لَهُ شَيْئًا إِلَّا كَانَ خَيْرًا لَهُ

God never decrees a thing for [the believer] except that it is good for him.

Musnad Aḥmad 19884 and Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān 729

God’s attitude toward the believer is only mercy; the hadith could be saying that God never, of His own volition, intends and wills evil for the believer. God does not like to watch us suffer.

This, however, does not address the question of God causing suffering to a believer as a test. Perhaps it means that if the believer was perfectly pious and sinless, they would not need any test or hardship and so nothing evil would ever befall them. God’s tests are there to teach us true submission to His will and power. If we reach the impossible standard of perfect submission, then that would be an end of tests and hardship–possibly.

God’s Guidance and the Sealing of Hearts

The Quranic verses on God guiding and misguiding humans or sealing the hearts of unbelievers have often been used to justify fatalism–the idea that humans absolutely have no role in the universe; their acts and choices are all created by God.

Had God willed, He would have made you one congregation, but He leaves astray whom He wills, and He guides whom He wills. And you will surely be questioned about what you used to do.

The Quran, verse 16:93

By believing that God causes all human choices, classical Sunni theologians believed that God can make something obligatory upon a person when it is impossible for them to do it. The classical example is the fact that God calls unbelievers to guidance, yet He Himself has supposedly sealed their hearts–making it impossible for them to be guided.

Based on what we have said so far, we can solve this problem by saying that God guides humans, but He also gives humans the freedom to accept or reject guidance. He shows us the truth, as He says:

We will show them Our signs on the horizons, and in their very souls, until it becomes clear to them that it is the truth. Is it not sufficient that your Lord is witness over everything?

The Quran, verse 41:53

But after showing us His signs, He lets us choose guidance or disbelief. Those who believe will be further guided by God, while those who disbelieve will be led astray:

As for those who believe and do good deeds, their Lord guides them by their faith. Rivers will flow beneath them in the Gardens of Bliss. (The Quran, verse 10:9)

Those who disbelieve say, “If only a miracle was sent down to him from his Lord.” Say, “God leads astray whomever He wills, and He guides to Himself whoever repents.” (The Quran, verse 13:27)

Guidance is therefore from God, but it is conditional upon human intentions. Those who believe, do good deeds and repent are blessed with further guidance. Those who disbelieve are caused to go further astray as a punishment. We can either choose guidance or reject it.

How will God guide a people who disbelieved after having believed, and had witnessed that the Messenger is true, and the clear proofs had come to them? God does not guide the unjust people.

The Quran, verse 3:86

The above verse says God will not guide unjust people who first believed then chose to reject the Prophet PBUH.

God’s guidance is not random. He does not force some people to go to Hell and some to Paradise as Ashʿarites and hadith scholars think. Rather, God allows us to choose our places in the Hellfire or Paradise. God knows whether we will be in the Hellfire or Paradise if we were to die this moment. He also knows all possible futures. But He has given us the freedom to erase what has been predetermined for us and change it based on our choices. You may be a sinner and God may have predestined you to have an unhappy life. But if you repent and become pious, God may rewrite your predestination so that He allows you to have a happier life.

As for the sealing of the hearts of unbelievers, it refers to those who have sinned and rejected God so severely and for so long that God has decided to seal their fate and prevent them from repenting.

Indeed, whoever commits misdeeds, and becomes surrounded by his iniquities—these are the inmates of the Fire, wherein they will dwell forever.

The Quran, verse 2:81

The Quran also says:

I will turn away from My revelations those who behave proudly on earth without justification. Even if they see every sign, they will not believe in it; and if they see the path of rectitude, they will not adopt it for a path; and if they see the path of error, they will adopt it for a path. That is because they denied Our revelations, and paid no attention to them.

The Quran, verse 7:146

God does not randomly seal hearts. He seals the hearts of those who commit so much evil that God decides they do not deserve to have the chance to repent. Once that happens, He seals their hearts and makes it impossible for them to ever seek repentance from Him.

The Remaining Paradox: God’s Foreknowledge

The creation of the future is a dynamic process between God and humanity. God constantly offers us multiple futures and we choose the ones we want to actually be in. We can never create a future God does not want because it is God who creates the futures. We only choose. Even if all of humanity wants to start a war, the futures God offers us may all lack the war. His will overrides humanity’s will and the war will never take place.

This, however, leads to the question: Does God know which future you will choose before you choose it? If God already knows which future you will choose, how can the choice possibly be free?

This is a logical paradox. If a decision is truly free, it seems like it should be unpredictable. Imagine that you create a robot that has free will. Even if you know everything there is to know about the robot, you will never be able to know what it will do next because its decisions are free. If you could always predict with 100% accuracy what the robot will always decide, then there is no free will involved. Freedom means to be able to make a genuine choice that comes from your inner self and that is not forced upon you from the outside by circumstances, or forced upon you by your brain chemistry. It is a genuine choice of the soul that is completely independent of the universe.

Saying that a free-willed decision is knowable before it is made may be as nonsensical as saying that God can make a 4-sided triangle, or that He can make an object so heavy that He Himself cannot move it. It is possible that free-willed human decisions are logically unknowable by their very nature because of the way God has made them. The decision is truly free and delegated to the human by God in a way that makes foreknowledge of it impossible (but there is an alternative view as will be discussed).

As mentioned, Ashʿarites, al-Ghazāli, al-Rāzī all say that God is utterly chained by His very nature into being incapable of creating free-willed creatures since He must create all intentions, wills and actions. God is incapable of making room for humans to be really, truly free.

So the question is this: Is God powerful enough to create a creature whose decision is so free that it is impossible to predict its decisions beforehand?

As far as I know, no Muslim theologian has ever posed that question directly.

Saying that God has foreknowledge of our decisions may be an insult against God’s power, because it suggests that God is incapable of producing a creature whose decision is so free that it is impossible to predict the decision beforehand. Is God incapable of making such a creature? Yet saying God does not have foreknowledge of our decisions may be an insult against His being All-Knowing.

Orthodox Muslim theologians like al-Rāzī chose to go with the first potential insult, saying God is incapable of making a truly free-willed creature, while non-orthodox Muʿtazilites went with the second potential insult, saying God is incapable of foreknowledge of human decisions.

We who know better should avoid both insults and choose a moderate path between them; leaving the judgment of these matters to God and relying on what we are certain about–the fact that we are responsible for our decisions, and the fact that God is utterly in charge of the universe.

Out of fear for God, we should not deny the possibility that God somehow knows all future decisions even before they are decided, even though this sounds like nonsense and like a contradiction of free will. We have very little knowledge of the world outside our universe and we do not know the true nature of God and His knowledge. Therefore rather than denying God’s foreknowledge, we should admit both possibilities:

- Either it is logically impossible for foreknowledge to apply to free-willed decisions. The future is a creative act between God and humans. In this view, saying it is possible to know a free-willed decision before it is made is nonsensical–it is like saying God can create a 4-sided triangle. God, of course, can predetermine the direction of the future, and no human can will anything He does not want. But He delegates some decisions to humans, and therefore this allows them to choose between different futures. It is logically impossible to know which future will be chosen before it is chosen because in order for a decision to be truly free, it should not be predictable. God Himself, with His infinite power and creativity, has chosen to create a creature who can make unpredictable decisions. Of course, when God wants, He can also force decisions on humans. We do not deny God’s power to do this.

- Or God has a mysterious power to know which future a human will choose even before he chooses it. In this view, God will already have a “film” of all of history, past and future, and nothing will change in it. This appears to completely contradict free will, but rather than denying it, out of fear for God, we leave its meaning to God. God knows everything that may possibly be known.

What we know for certain from the Quran is that we are responsible for our decisions. We also know that God is utterly in charge of our destinies. We also know that fatalism is forbidden–we cannot say that it is already predetermined whether we will be in Paradise or Hell so that there is no point in good deeds:

The polytheists will say, “Had God willed, we would not have practiced idolatry, nor would have our forefathers, nor would we have prohibited anything.” Likewise those before them lied, until they tasted Our might. Say, “Do you have any knowledge that you can produce for us? You follow nothing but conjecture, and you only guess.” (6:148)

However, we must also reject al-Rāzī’s statement that humans only appear to be free. It is mere conjecture. Rather, we should say that we simply do not know the solution to the paradox and that we leave the matter to God. As far as we know, we are free in our choices, God is utterly in charge, and whether His foreknowledge applies to our future decisions or not is a dangerous matter that we leave to God. Logically it appears that foreknowledge should not apply to free will, but we admit that God is so great and so infinitely beyond our knowledge that we say logic is not necessarily sufficient to override the possibility of God’s foreknowledge.

The Predestination of Prophets

He said, “I am only the messenger of your Lord, to give you the gift of a pure son.”

The Quran, verse 19:19

In the above verse, an angel tells Mary mother of Jesus that she will have a “pure” son. This means that Jesus was predestined to be pure. We see the same in the case of John (Prophet Yaḥyā):

Then the angels called out to him, as he stood praying in the sanctuary: “God gives you good news of John; confirming a Word from God, and honorable, and moral, and a prophet; one of the upright.”

The Quran, verse 3:39

Above, Zechariah is told that his unborn son will be honorable, moral and upright, as if John himself would have no say in the matter. This does not nullify free will in general. What it means is that certain chosen individuals will be protected by God from sins and disbelief. As we said above, humans only intend, but God creates the will in them to do good or bad. In the case of the prophets, even if they willed something bad, God could override their will and prevent them from carrying out the sin.

While the generality of humans enjoy free will, prophets enjoy a more restricted free will that is under God’s divine guidance and control. In this way God can have a plan for a prophet even before the prophet’s birth and ensure that His plan is fully carried out. He may give the prophet sufficient free will for them to be human to some degree, while preventing them from ever deviating from His plan.

The same protection is also likely enjoyed by pious believers. God eases them toward good deeds and makes evil deeds difficult for them by overriding their will when He wants and restricting their freedom to sin as a favor upon them. But when it comes to impious and rebellious people, God takes away His protection:

Whoever makes a breach with the Messenger, after the guidance has become clear to him, and follows other than the path of the believers, We will direct him in the direction he has chosen, and commit him to Hell—what a terrible destination!

The Quran, verse 4:115

On Contradicting Hadith Narrations

Numerous hadiths suggest that people are condemned to Paradise or Hell even before they are born. These hadiths seem to completely contradict free will and divine justice. Due to the great number of hadiths on this issue and their conflicting nature, I have dedicated a supplementary essay to it here: A Study of the Hadiths on Qadar (Predestination): Judging Between Fatalism and Free Will

My conclusion in that essay is that the hadith literature is not conclusive in forcing fatalism on us. We have the choice to reject fatalism, and since rejecting it is the more sensible and Quranic choice, and since it is supported by multiple authentic narrations, then this should be the choice of someone who prefers the theological worldview I have described here in this essay.

We know that Imam al-Bukhārī rejected a few authentic narrations when he considered their meaning absurd, as Jonathan Brown’s studies have shown.1 Imam Mālik too refused to act by certain authentic hadith narrations when they went against the practice of the people of Medina (see the PhD dissertation The Origins of Islamic Law: The Qur’an, the Muwatta’ and Madinan Amal by Yasin Dutton). We may never know, but perhaps if Imam al-Bukhārī had been against fatalism, he would have considered fatalistic narrations to be unauthentic regardless of their chains.

Ibn Taymiyya and his student Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya both rejected fatalism and did their best to reinterpret fatalistic hadith narrations to make room for true free choice and the possibility of change in a person’s fate; see Livnat Holtzman’s essay in Ibn Taymiyya and His Times.

Conclusion

We know for certain that we are responsible for our actions. This should be the basis of our thinking about these matters. Suppositions about predetermination and divine foreknowledge should never dishearten us from doing goods deeds and avoiding sin, because we should not abandon a certainty (our responsibility) for the sake of speculations.

In summary, we accept human responsibility, divine predetermination of the alternative futures, the possibility of change in destinies, and the possibility of true human free will. We affirm God’s All-Knowing and All-Powerful attributes, that He is utterly in charge of the universe, that no human can will anything unless God allows it and creates the will. We also admit the paradox between free will and divine foreknowledge and leave its ultimate solution to God. We do not want to say there is anything God does not know. But there is no shame in God being powerful enough to create a creature who is free enough to make decisions that are intrinsically impossible to predict. This affirms His attribute of the All-Powerful, even if on the face of it it appears to go against His attribute of the All-Knowing. Since we have no firm knowledge of these matters, we leave their ultimate solution to God: it may be an insult against God to deny the possibility of true, impossible-to-predict free will (because it suggests God is incapable of making such a thing), and it may also be an insult against God to say that future human decisions are impossible to predict (because it suggests God does not know future human decisions).

God allows us to choose between alternative futures, but all futures are created by God. Prayer is beneficial because God may respond by creating brand-new alternative futures that did not exist before and that contain many blessings that we wouldn’t have had access to otherwise. We can never escape God’s decree, but we can affect what God decrees for us by our piety or sinfulness. If we are pious, God rewards us by decreeing good things, and if we are sinful, God may punish us by decreeing bad things for us. This is what the plain meaning of the Quran and the Prophet’s PBUH statement on prayer changing one’s predestiny suggest.